Bath physicists' discovery of a new way to manipulate light a million times more efficiently than before

Using a special hollow-core photonic crystal fibre, a team at the University of Bath, UK, has opened the door to what could prove to be a new sub-branch of photonics, the science of light guidance and trapping. The team, led by Dr Fetah Benabid, reports on the discovery, which relates to the emerging attotechnology, the ability to send out pulses of light that last only an attosecond, a billion billionth of a second.

These pulses are so brief that they allow researchers to more accurately measure the movement of sub-atomic particles such as the electron, the tiny negatively-charged entity which moves outside the nucleus of an atom. Attosecond technology may throw light, literally, upon the strange quantum world where such particles have no definite position,only probable locations.

To make attosecond pulses, researchers create a broad spectrum of light from visible wavelengths to x-rays through an inert gas. This normally requires a gigawatt of power, which puts the technique beyond any commercial or industrial use.

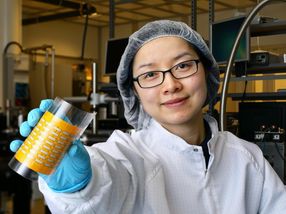

But Dr Benabid's team used a photonic crystal fibre (pcf), the width of a human hair, which traps light and the gas together in an efficient way. Until now the spectrum produced by photonic crystal fibre has been too narrow for use in attosecond technology, but the team have now produced a broad spectrum, using what is called a Kagomé lattice, using about a millionth of the power used by non-pcf methods.

"This new way of using photonic crystal fibre has meant that the goal of attosecond technology is much closer," said Dr Benabid, of the University of Bath's Department of Physics, who worked with students Mr Francois Couny and Mr Phil Light, and with Dr John Roberts of the Technical University of Denmark and Dr Michael Raymer of the University of Oregon, USA.

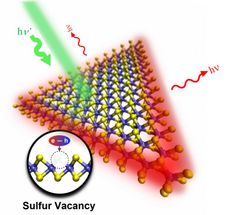

Dr Benabid's team has not only made an important step in applied physics, but has contributed to the theory of photonics too. The effectiveness of photonic crystal fibre has lain so far in its exploitation of what is called photonic band gap, which stops photons of light from "existing" in the fibre cladding and enabled them to be trapped in the inside core of the fibre.

Instead, the team makes use of the fact that light can exist in different 'modes' without strongly interacting. This creates a situation whereby light can be trapped inside the fibre core without the need of photonic bandgap. Physicists call these modes bound states within a continuum.

Most read news

Other news from the department science

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.