Scientists unravel how natural gas is converted into methanol at room temperature

Twenty years after the technique was developed, scientists at KU Leuven and Stanford University have unravelled the mechanism behind the direct conversion process of natural gas into Methanol at room temperature. This discovery will have major consequences for the future use of methanol in various everyday applications.

Methanol is among the twenty most commonly used substances in the chemical industry. It’s used to produce antifreeze, fuels, and solvents, but also in common types of plastic. The substance is made from natural gas (methane). The large-scale conversion of methane into methanol currently involves various steps under high pressure and at a high temperature, making it a process that requires a lot of energy.

In the nineties, scientists developed a more direct method to produce methanol – a process that even produces extra energy. However, they didn’t really understand the process. It was a kind of ‘black box’ into which they inserted methane, with a big chance that methanol would come out at the other end.

Twenty years later, postdoctoral researcher Pieter Vanelderen from the Centre for Surface Chemistry and Catalysis at KU Leuven has unravelled the mechanism behind the process, in collaboration with chemists from Stanford University.

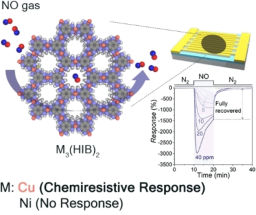

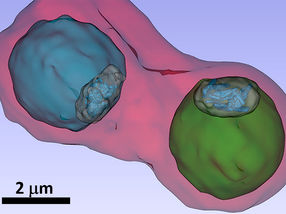

The chemical reaction involves adding a specific substance known as a catalyst. Many catalysts consist of zeolites – minerals with a porous framework – that contain a specific atom. For the direct conversion of methane into methanol, this catalyst is a zeolite with added iron. Professor Bert Sels: “we found that the iron needs to bind to the zeolite in a flat, bound orientation”.

“We have provided the first exact definition of what the iron atom looks like that is needed to convert methane into methanol at room temperature. Furthermore, we can describe why this conversion method is so successful,” explains Pieter Vanelderen. This discovery may revolutionize the production of methanol and, by extension, all its derivatives that we use in our everyday lives.

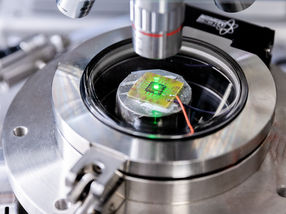

“This breakthrough was only possible because we as chemists were the first to join forces with biochemists to work on this topic,” says Vanelderen. “Our colleagues at Stanford are specialized in the use of enzymes as catalysts in chemical reactions. Using methods initially developed to study iron-containing enzymes, they managed to take a ‘picture’, as it were, of what it is that happens to this iron-containing zeolite during the conversion of methane into methanol. This information allowed us to determine which specific iron atom was doing the work and to find its exact location in the zeolite.”

Now that scientists know exactly what the catalyst looks like, they can start imitating and optimizing it in the lab. This opens up quite a few possibilities for the future. For one thing, the production of the methanol needed to produce plastic will become a lot cheaper. The catalyst is also useful for the conversion of nitrogen oxides. It could be used, for instance, to clean the exhaust fumes of cars.

Original publication

Most read news

Original publication

Benjamin E. R. Snyder, Pieter Vanelderen, Max L. Bols, Simon D. Hallaert, Lars H. Böttger, Liviu Ungur, Kristine Pierloot, Robert A. Schoonheydt, Bert F. Sels & Edward I. Solomon; "The active site of low-temperature methane hydroxylation in iron-containing zeolites"; Nature; 2016

Topics

Organizations

Other news from the department science

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.

![[Fe]-hydrogenase catalysis visualized using para-hydrogen-enhanced nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy](https://img.chemie.de/Portal/News/675fd46b9b54f_sBuG8s4sS.png?tr=w-712,h-534,cm-extract,x-0,y-16:n-xl)