New polymer creates safer fuels

Before embarking on a transcontinental journey, jet airplanes fill up with tens of thousands of gallons of fuel. In the event of a crash, such large quantities of fuel increase the severity of an explosion upon impact. Researchers at Caltech and JPL have discovered a polymeric fuel additive that can reduce the intensity of postimpact explosions that occur during accidents and terrorist acts. Furthermore, preliminary results show that the additive can provide this benefit without adversely affecting fuel performance.

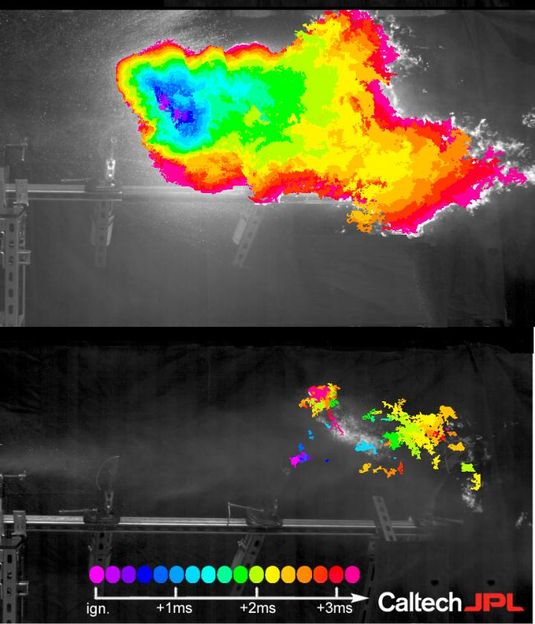

This photograph shows the progress of the flame after ignition in a post-impact mist of Jet-A fuel treated with prior ultra-long polymers (upper) and the Caltech polymer (lower) after the samples have passed through a fuel pump 50 times. The efficacy of prior polymers is lost, and a large, hot fireball ensues. The Caltech polymer retains its ability to mitigate post-impact fire: the chains do not break, rather they release from one another as they pass through the pump and reassemble again into mega-supramolecules. The color scale shows the progression of the flame with time.

Caltech/JPL

Jet engines compress air and combine it with a fine spray of jet fuel. Ignition of the mixture of air and jet fuel by an electric spark triggers a controlled explosion that thrusts the plane forward. Jet airplanes are powered by thousands of these tiny explosions. However, the process that distributes the spray of fuel for ignition also causes fuel to rapidly disperse and easily catch fire in the event of an impact.

The additive, created in the laboratory of Julia Kornfield, professor of chemical engineering, is a type of polymer capped at each end by units that act like Velcro. The individual polymers spontaneously link into ultralong chains called "megasupramolecules."

Megasupramolecules, Kornfield says, have an unprecedented combination of properties that allows them to control fuel misting, improve the flow of fuel through pipelines, and reduce soot formation. Megasupramolecules inhibit misting under crash conditions and permit misting during fuel injection in the engine.

Other polymers have shown these benefits, but have deficiencies that limit their usefulness. For example, ultralong polymers tend to break irreversibly when passing through pumps, pipelines, and filters. As a result, they lose their useful properties. This is not an issue with megasupramolecules, however. Although supramolecules also detach into smaller parts as they pass through a pump, the process is reversible. The Velcro-like units at the ends of the individual chains simply reconnect when they meet, effectively "healing" the megasupramolecules.

When added to fuel, megasupramolecules dramatically affect the flow behavior even when the polymer concentration is too low to influence other properties of the liquid. For example, the additive does not change the energy content, surface tension, or density of the fuel. In addition, the power and efficiency of engines that use fuel with the additive is unchanged--at least in the diesel engines that have been tested so far.

When an impact occurs, the supramolecules spring into action. The supramolecules spend most of their time coiled up in a compact conformation. When there is a sudden elongation of the fluid, however, the polymer molecules stretch out and resist further elongation. This stretching allows them to inhibit the breakup of droplets under impact conditions as well as to reduce turbulence in pipelines.

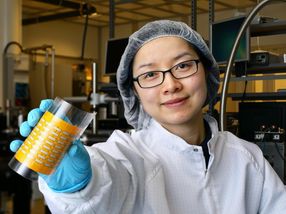

When Wei joined the project in 2007, he set out to create these theoretical molecules. Producing polymers of the desired length with sufficiently strong "molecular Velcro" on both ends proved to be a challenge. With the help of a catalyst developed by Robert Grubbs, the Victor and Elizabeth Atkins Professor of Chemistry and winner of the 2005 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, Wei developed a method to precisely control the structure of the molecular Velcro and put it in the right place on the polymer chains.

"Looking to the future, if you want to use this additive in thousands of gallons of jet fuel, diesel, or oil, you need a process to mass-produce it," Wei says. "That is why my goal is to develop a reactor that will continuously produce the polymer--and I plan to achieve it less than a year from now."

"Above all," Kornfield says, "we hope these new polymers will save lives and minimize burns that result from postimpact fuel fires."