Atomic Fractals in Metallic Glasses

metallic glasses are very strong and elastic materials that appear with the naked eye to be identical to stainless steel. But metallic glasses differ from ordinary metals in that they are amorphous, lacking an orderly, crystalline atomic arrangement. This random distribution of atoms, which is the primary characteristic of all glass materials, gives metallic glasses unique mechanical properties but unpredictable internal structure. Researchers in the Caltech lab of Julia Greer, professor of materials science and mechanics in the Division of Engineering and Applied Science, have shown that metallic glasses do have an atomic-level structure although it differs from the periodic lattices that characterize crystalline metals.

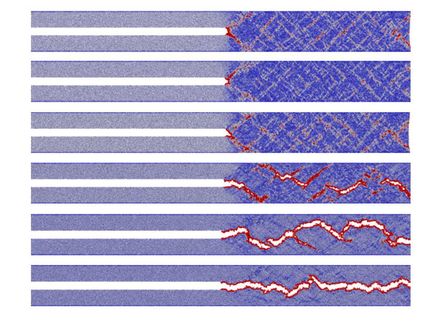

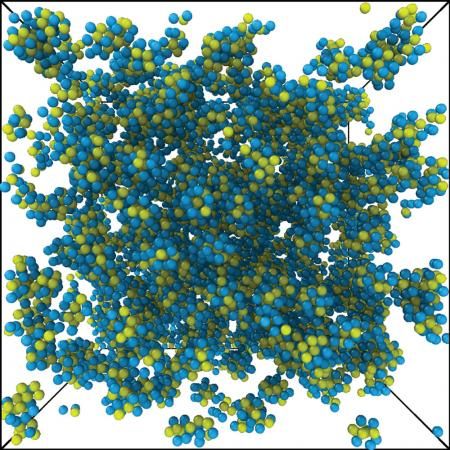

An illustration of what the atomic fractal percolation structure may look like

Courtesy David Chen/Greer Laboratory/Caltech

If you looked at a metallic glass on a scale larger than a few atomic diameters, you would see tightly packed, jumbled clusters of atoms. A new study from the Greer group shows that inside each of these clusters, on a scale of about two to three atomic diameters, atoms have a predictable arrangement called a fractal.

Fractals are patterns that are self-similar on different scales, and they can occur quite naturally.

"Take for example a piece of paper crumpled into a ball. If you look at the folds of the paper when it is flattened back after crumpling, it will look qualitatively the same if you zoom in on a smaller portion of the same paper. The scale that you use to examine the paper more or less does not change the way it looks," says David Chen, a fourth-year graduate student in the Greer lab and first author on this new paper.

The group did simulations and experiments to probe the atomic structure of metallic glass alloys of copper, zirconium, and aluminum. In crystalline solids like diamond or gold, atoms or molecules are arranged in an orderly lattice pattern. As a result, the local neighborhood around an atom in a crystalline material is identical to everywhere else in the material. In amorphous metals, every location within the material looks different - except, Greer and her colleagues found, when you zoom in to look at the distribution of atoms at the scale of two to three atomic diameters - about one nanometer. At this level, the same fractal pattern is present, regardless of location within the material. "Within the clusters of atoms that make up a metallic glass, atoms are arranged in a particular kind of fractal pattern called percolation," Chen says.

Other scientists have previously hypothesized that the atoms in metallic glasses are distributed fractally. However, this creates an apparent paradox: When atoms are distributed fractally, there should be empty space between them. However, metallic glasses are fully dense, meaning that they lack significant pockets of empty space.

"Our group has solved this paradox by showing that atoms are only arranged fractally up to a certain scale," Greer says. "Larger than that scale, clusters of atoms are packed randomly and tightly, making a fully dense material, just like a regular metal. So we can have something that is both fractal and fully dense."

The discovery was made with metallic glasses, but the group's conclusions about fractally arranged atomic structures can be applied to essentially any rigid amorphous material, like the glass in a windowpane or a frozen piece of chewing gum. "Amorphous metals can exhibit unique properties, like unusual strength and elasticity," Chen says. "Now that we know the structure of these materials, we can start studying how their atomic-level arrangement affects their large-scale properties."

In addition to applications within materials science, studies of naturally occurring fractal distributions are of high interest within the fields of mathematics, physics, and computer science. Fractals have been studied for centuries by mathematicians and physicists. Showing how they emerge in a metallic alloy provides a physical foundation for something that has only been studied theoretically.