New method allows for greater variation in band gap tunability

The method can change a material's electronic band gap by up to 200 percent

Northwestern University's James Rondinelli uses quantum mechanical calculations to predict and design the properties of new materials by working at the atom-level. His group's latest achievement is the discovery of a novel way to control the electronic band gap in complex oxide materials without changing the material's overall composition. The finding could potentially lead to better electro-optical devices, such as lasers, and new energy-generation and conversion materials, including more absorbent solar cells and the improved conversion of sunlight into chemical fuels through photoelectrocatalysis.

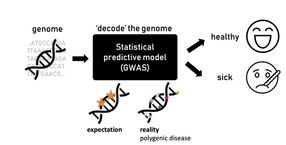

"There really aren't any perfect materials to collect the sun's light," said Rondinelli, assistant professor of materials science and engineering in the McCormick School of Engineering. "So, as materials scientists, we're trying to engineer one from the bottom up. We try to understand the structure of a material, the manner in which the atoms are arranged, and how that 'genome' supports a material's properties and functionality."

The electronic band gap is a fundamental material parameter required for controlling light harvesting, conversion, and transport technologies. Via band-gap engineering, scientists can change what portion of the solar spectrum can be absorbed by a solar cell, which requires changing the structure or chemistry of the material.

Current tuning methods in non-oxide semiconductors are only able to change the band gap by approximately one electronvolt, which still requires the material's chemical composition to become altered. Rondinelli's method can change the band gap by up to 200 percent without modifying the material's chemistry. The naturally occurring layers contained in complex oxide materials inspired his team to investigate how to control the layers. They found that by controlling the interactions between neutral and electrically charged planes of atoms in the oxide, they could achieve much greater variation in electronic band gap tunability.

"You could actually cleave the crystal and, at the nanometer scale, see well-defined layers that comprise the structure," he said. "The way in which you order the cations on these layers in the structure at the atomic level is what gives you a new control parameter that doesn't exist normally in traditional semiconductor materials."

By tuning the arrangement of the cations - ions having a net positive, neutral, or negative charge - on these planes in proximity to each other, Rondinelli's team demonstrated a band gap variation of more than two electronvolts. "We changed the band gap by a large amount without changing the material's chemical formula," he said. "The only difference is the way we sequenced the 'genes' of the material."

"Today it's possible to create digital materials with atomic level precision," Rondinelli said. "The space for exploration, however, is enormous. If we understand how the material behavior emerges from building blocks, then we make that challenge surmountable and meet one of the greatest challenges today--functionality by design."

Other news from the department science

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

From now on, don't miss a thing: Our newsletter for the chemical industry, analytics, lab technology and process engineering brings you up to date every Tuesday and Thursday. The latest industry news, product highlights and innovations - compact and easy to understand in your inbox. Researched by us so you don't have to.