New laser-patterning technique turns metals into supermaterials

Hierarchical nano- and microstructures transform sheets of platinum, titanium and brass into light absorbing, water repelling, self-cleaning superstars

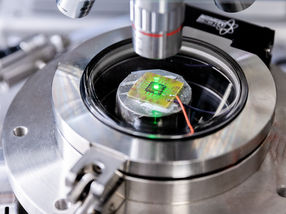

By zapping ordinary metals with femtosecond laser pulses researchers from the University of Rochester in New York have created extraordinary new surfaces that efficiently absorb light, repel water and clean themselves. The multifunctional materials could find use in durable, low maintenance solar collectors and sensors.

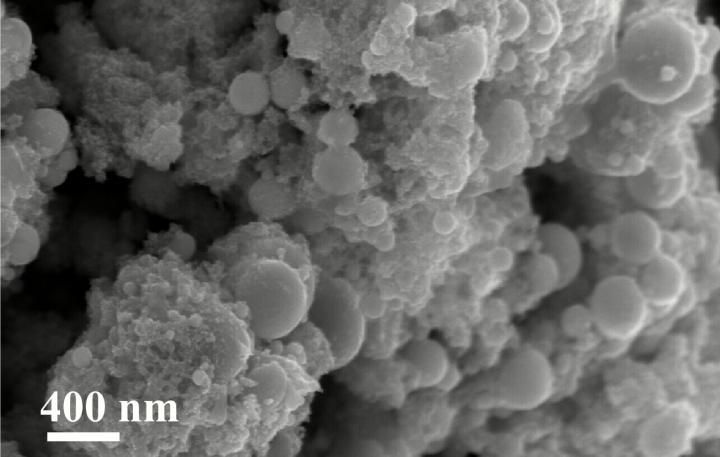

A femtosecond laser created detailed hierarchical structures in the metals, as shown in this SEM image of the platinum surface

The Guo Lab/University of Rochester

"This is the first time that a multifunctional metal surface is created by lasers that is superhydrophobic (water repelling), self-cleaning, and highly absorptive," said Chunlei Guo, a physicist at the Institute of Optics at the University of Rochester who made the new surfaces with his colleague and fellow University of Rochester researcher Anatoliy Vorobyev.

Enhanced light absorption will benefit technologies that require light collection, such as sensors and solar power devices, while superhydrophobicity will make a surface rust-resistant, anti-icing and anti-biofouling, all of which could help make such devices more robust and easier to maintain, Guo said. The superhydrophobic surfaces can also clean themselves, since water droplets repelled from the surface carry away dust particles very efficiently.

The researchers created the surfaces by zapping platinum, titanium and brass samples with extremely short femtosecond laser pulses that lasted on the order of a millionth of a billionth of a second. "During its short burst the peak power of the laser pulse is equivalent to that of the entire power grid of North America," Guo said.

These extra-powerful laser pulses produced microgrooves, on top of which densely populated, lumpy nanostructures were formed. The structures essentially alter the optical and wetting properties of the surfaces of the three metals, turning the normally shiny surfaces velvet black (very optically absorptive) and also making them water repellent.

Most commercially used hydrophobic and high optical absorption materials rely on chemical coatings that can degrade and peel off over time, said Guo. Because the nano- and microstructures created by the lasers are intrinsic to the metal, the properties they confer should not deteriorate, he said.

The hydrophobic properties of the laser-patterned metals also compare favorably with a famous non-stick coating. "Many people think of Teflon as a hydrophobic surface, but if you want to get rid of water from a Teflon surface, you will have to tilt the surface to nearly 70 degrees before the water can slide off," Guo said. "Our surface has a much stronger hydrophobicity and requires only a couple of degrees of tilt for water to slide off."

Guo and his colleagues have a lot of experience changing the properties of materials with lasers. A couple of years ago, they used lasers to create a superhydrophilic (water attracting) surface that was so strong that water ran uphill against gravity. "After that, we were motivated to create the counterpart technology, making a surface to repel water," Guo said.

The team has plans to work on creating multifunctional effects on other materials, such as semiconductors and dielectrics. The multifunctional effects should find a wide range of applications such as making better solar energy collectors.

![[Fe]-hydrogenase catalysis visualized using para-hydrogen-enhanced nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy](https://img.chemie.de/Portal/News/675fd46b9b54f_sBuG8s4sS.png?tr=w-712,h-534,cm-extract,x-0,y-16:n-xl)