International team of researchers presents a milestone in chemical studies of superheavy elements

Chemical bond between a superheavy element and a carbon atom established for the first time

An international collaboration led by research groups from Mainz and Darmstadt, Germany, has achieved the synthesis of a new class of chemical compounds for superheavy elements at the RIKEN Nishina Center for Accelerator-based Research (RNC) in Japan. For the first time, a chemical bond was established between a superheavy element – seaborgium (element 106) in the present study – and a carbon atom. Eighteen atoms of seaborgium were converted into seaborgium hexacarbonyl complexes, which include six carbon monoxide molecules bound to the seaborgium. Its gaseous properties and adsorption to a silicon dioxide surface were studied, and compared with similar compounds of neighbors of seaborgium in the same group of the periodic table. The study opens perspectives for much more detailed investigations of the chemical behavior of elements at the end of the periodic table, where the influence of effects of relativity on chemical properties is most pronounced.

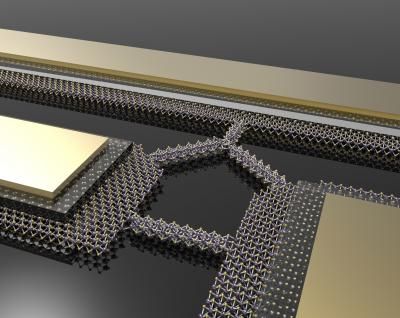

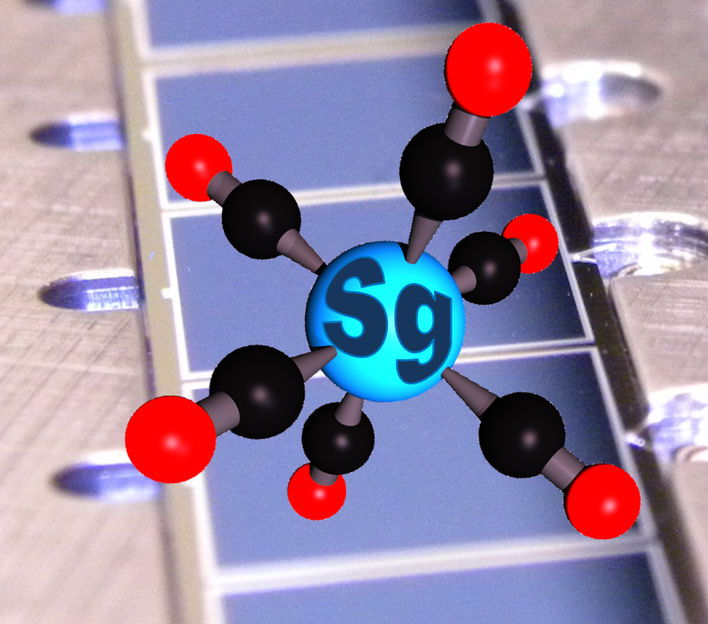

Graphic representation of a seaborgium hexacarbonyl molecule on the silicon dioxide covered detectors of a COMPACT detector array

Alexander Yakushev (GSI) / Christoph E. Düllmann (JGU)

Chemical experiments with superheavy elements – with atomic number beyond 104 – are most challenging: First, the very element to be studied has to be artificially created using a particle accelerator. Maximum production rates are on the order of a few atoms per day at most, and are even less for the heavier ones. Second, the atoms decay quickly through radioactive processes – in the present case within about 10 seconds, adding to the experiment's complexity. A strong motivation for such demanding studies is that the very many positively charged protons inside the atomic nuclei accelerate electrons in the atom's shells to very high velocities – about 80 percent of the speed of light. According to Einstein's theory of relativity, the electrons become heavier than they are at rest. Consequently, their orbits may differ from those of corresponding electrons in lighter elements, where the electrons are much slower. Such effects are expected to be best seen by comparing properties of so-called homologue elements, which have a similar structure in their electronic shell and stand in the same group in the periodic table. This way, fundamental underpinnings of the periodic table of the elements – the standard elemental ordering scheme for chemists all around the world – can be probed.

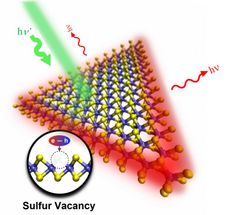

Chemical studies with superheavy elements often focus on compounds, which are gaseous already at comparatively low temperatures. This allows their rapid transport in the gas phase, benefitting a fast process as needed in light of the short lifetimes. To date, compounds containing halogens and oxygen have often been selected; as an example, seaborgium was studied previously in a compound with two chlorine and two oxygen atoms – a very stable compound with high volatility. However, in such compounds, all of the outermost electrons are occupied in covalent chemical bonds, which may mask relativistic effects. The search for more advanced systems, involving compounds with different bonding properties that exhibit effects of relativity more clearly, continued for many years.

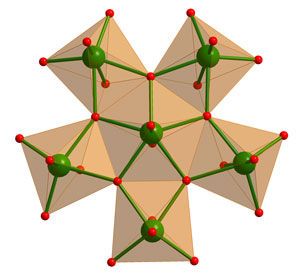

In the preparation for the current work, the superheavy element chemistry groups at the Institute for Nuclear Chemistry at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU), the Helmholtz Institute Mainz (HIM), and the GSI Helmholtz Center for Heavy Ion Research (GSI) in Darmstadt together with Swiss colleagues from the Paul Scherrer Institute, Villigen, and the University of Berne developed a new approach, which promised to allow chemical studies with single, short-lived atoms also for compounds which were less stable. Initial tests were carried out at the TRIGA Mainz research reactor and were shown to work exceptionally well with short-lived atoms of molybdenum. The method was elaborated at Berne University and in accelerator experiments at GSI. Dr. Alexander Yakushev from the GSI team explains: "A big challenge in such experiments is the intense accelerator beam, which destroys even moderately stable chemical compounds. To overcome this problem, we first sent tungsten, the heavier neighbor of molybdenum, through a magnetic separator and separated it from the beam. Chemical experiments were then performed behind the separator, where conditions are ideal to study also new compound classes." The focus was on the formation of hexacarbonyl complexes. Theoretical studies starting in the 1990s predicted these to be rather stable. Seaborgium is bound to six carbon monoxide molecules through metal-carbon bonds, in a way typical of organometallic compounds, many of which exhibit the desired electronic bond situation the superheavy element chemists were dreaming of for long.

The Superheavy Element Group at the RNC in Wako, Japan, optimized the seaborgium production in the fusion process of a neon beam (element 10) with a curium target (element 96) and isolated it in the GAs-filled Recoil Ion Separator (GARIS). Dr. Hiromitsu Haba, team leader at RIKEN, explains: "In the conventional technique for producing superheavy elements, large amounts of byproducts often disturb the detection of single atoms of superheavy elements such as seaborgium. Using the GARIS separator, we were able at last to catch the signals of seaborgium and evaluate its production rates and decay properties. With GARIS, seaborgium became ready for next-generation chemical studies."

In 2013, the two groups teamed up, together with colleagues from Switzerland, Japan, the United States, and China, to study whether they could synthesize a superheavy element compound like seaborgium hexacarbonyl. In two weeks of round-the-clock experiments, with the German chemistry setup coupled to the Japanese GARIS separator, 18 seaborgium atoms were detected. The gaseous properties as well as the adsorption on a silicon dioxide surface were studied and found to be similar to those of the corresponding hexacarbonyls of the homologs molybdenum and tungsten – very characteristic compounds of the group-6 elements in the periodic table – adding proof to the identity of the seaborgium hexacarbonyl. The measured properties were in agreement with theoretical calculations, in which the effects of relativity were included.

Dr. Hideto En'yo, the director of RNC says: "This breakthrough experiment could not have succeeded without the powerful and tight collaboration between fourteen institutes around the world." Prof. Frank Maas, the director of the HIM, says "The experiment represents a milestone in chemical studies of superheavy elements, showing that many advanced compounds are within reach of experimental investigation. The perspectives that this opens up for gaining more insight into the nature of chemical bonds, not only in superheavy elements, are fascinating."

Following this first successful step along the path to more detailed studies of the superheavy elements, the team already has plans for further studies of yet other compounds, and with even heavier elements than seaborgium. Soon, Einstein may have to show the deck in his hand with which he twists the chemical properties of elements at the end of the periodic table.