Palladium-gold nanoparticles clean TCE a billion times faster than iron filings

In the first side-by-side tests of a half-dozen palladium- and iron-based catalysts for cleaning up the carcinogen TCE, Rice University scientists have found that palladium destroys TCE far faster than iron -- up to a billion times faster in some cases. The results will appear in a new study in the August issue of the journal Applied Catalysis B: Environmental.

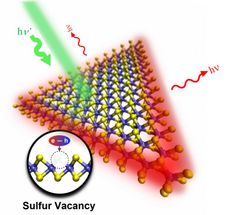

TCE, or trichloroethene, is a widely used chemical degreaser and solvent that's found its way into groundwater supplies the world over. The TCE molecule, which contains two carbon atoms and three chlorine atoms, is very stable. That stability is a boon for industrial users, but it's a bane for environmental engineers.

"It's difficult to break those bonds between chlorine and carbon," said study author Michael Wong, professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering and of chemistry at Rice. "Breaking some of the bonds, instead of breaking all the carbon-chlorine bonds, is a huge problem with some TCE treatment methods. Why? Because you make byproducts that are more dangerous than TCE, like vinyl chloride.

"The popular approaches are, thus, those that do not break these bonds. Instead, people use air-stripping or carbon adsorption to physically remove TCE from contaminated groundwater," Wong said. "These methods are easy to implement but are expensive in the long run. So, reducing water cleanup cost drives interest in new and possibly cheaper methods."

In the U.S., TCE is found at more than half the contaminated waste sites on the Environmental Protection Agency's Superfund National Priorities List. At U.S. military bases alone, the Pentagon has estimated the cost of removing TCE from groundwater to be more than $5 billion.

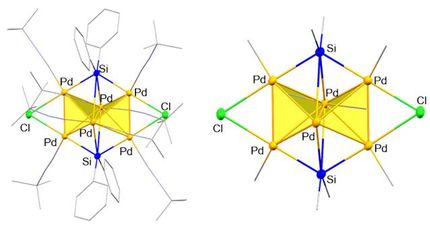

In the search for new materials that can break down TCE into nontoxic components, researchers have found success with pure iron and pure palladium. In the former case, the metal degrades TCE as it corrodes in water, though sometimes vinyl chloride is formed. In the latter case, the metal acts as a catalyst; it doesn't react with the TCE itself, but it spurs reactions that break apart the troublesome carbon-chlorine bonds. Because iron is considerably cheaper than palladium and easier to work with, it is already used in the field. Palladium, on the other hand, is still limited to field trials.

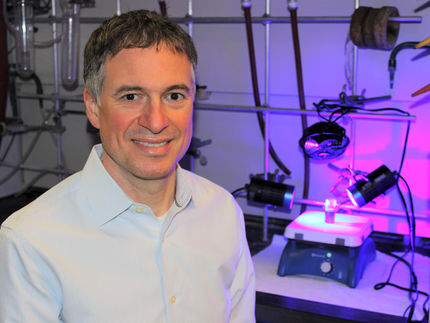

Wong led the development of a gold-palladium nanoparticle catalyst approach for TCE remediation in 2005. He found it was difficult to accurately compare the new technology with other iron- and palladium-based remediation schemes because no side-by-side tests had been published.

"People knew that iron was slower than palladium and palladium-gold, but no one knew quantitatively how much slower," he said.

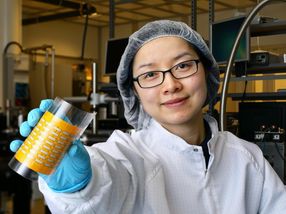

In the new study, a team including Wong and lead author Shujing Li, a former Rice visiting scholar from Nankai University, China, ran a series of tests on various formulations of iron and palladium catalysts. The six included two types of iron nanoparticles, two types of palladium nanoparticles -- including Wong's palladium-gold particle -- and powdered forms of iron and palladium-aluminum oxide.

The researchers prepared a solution of water contaminated with TCE and tested each of the six catalysts to see how long they took to break down 90 percent of the TCE in the solution. This took less than 15 minutes for each of the palladium catalysts and more than 25 hours for the two iron nanoparticles. For the iron powder, it took more than 10 days.

"We knew from previous studies that palladium was faster, but I think everyone was a bit surprised to see how much faster in these side-by-side tests," Li said.

Wong said the new results should be helpful to those who are trying to compare the costs of conducting large-scale tests on catalytic remediation of TCE.

Most read news

Organizations

Other news from the department science

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.