University of Virginia researchers uncover new catalysis site

Mention catalyst and most people will think of the catalytic converter, an emissions control device in the exhaust system of automobiles that reduces pollution.

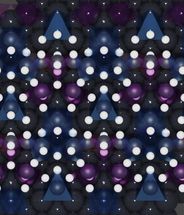

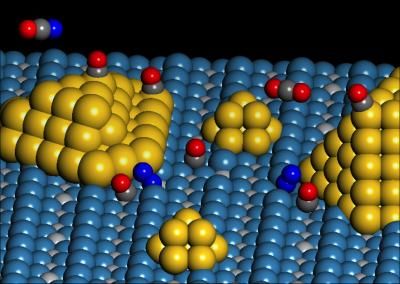

Image of a dual catalytic site causing the catalytic activation of an oxygen molecule (dark blue) at the perimeter of a gold nanoparticle held on a titanium dioxide support. A carbon dioxide molecule, produced by oxidation of adsorbed carbon monoxide, is liberated.

Image by Matthew Neurock, University of Virginia

But catalysts are used for a broad variety of purposes, including the conversion of petroleum and renewable resources into fuel, as well as the production of plastics, fertilizers, paints, solvents, pharmaceuticals and more. About 20 percent of the gross domestic product in the United States depends upon catalysts to facilitate the chemical reactions needed to create products for everyday life.

Catalysts are materials that activate desired chemical reactions without themselves becoming altered in the process. This allows the catalysts to be used continuously because they do not readily deteriorate and are not consumed in the chemical reactions they inspire.

Chemists long ago discovered and refined many catalysts and continue to do so, though the details of the mechanisms by which they work often are not understood.

A new collaborative study at the University of Virginia details for the first time a new type of catalytic site where oxidation catalysis occurs, shedding new light on the inner workings of the process. The study, conducted by John Yates, a professor of chemistry in the College and Graduate School of Arts & Sciences, and Matthew Neurock, a professor of chemical engineering in the School of Engineering and Applied Science, will be published in the Aug. 5 issue of the journal Science.

Yates said the discovery has implications for understanding catalysis with a potentially wide range of materials, since oxidation catalysis is critical to a number of technological applications.

"We have both experimental tools, such as spectrometers, and theoretical tools, such as computational chemistry, that now allow us to study catalysis at the atomic level," he said. "We can focus in and find that sweet spot more efficiently than ever. What we've found with this discovery could be broadly useful for designing catalysts for all kinds of catalytic reactions."

Using a titanium dioxide substrate holding nanometer-size gold particles, U.Va. chemists and chemical engineers found a special site that serves as a catalyst at the perimeter of the gold and titanium dioxide substrate.

"The site is special because it involves the bonding of an oxygen molecule to a gold atom and to an adjacent titanium atom in the support," Yates said. "Neither the gold nor the titanium dioxide exhibits this catalytic activity when studied alone."

Using spectroscopic measurements combined with theory, the Yates and Neurock team were able to follow specific molecular transformations and determine precisely where they occurred on the catalyst.

The experimental and theoretical work, guided by Yates and Neurock, was carried out by Isabel Green, a U.Va. Ph.D. candidate in chemistry, and Wenjie Tang, a research associate in chemical engineering. They demonstrated that the significant catalytic activity occurred on unique sites formed at the perimeter region between the gold particles and their titania support.

"We call it a dual catalytic site because two dissimilar atoms are involved," Yates said.

They saw that an oxygen molecule binds chemically to both a gold atom at the edge of the gold cluster and a nearby titanium atom on the titania support and reacts with an adsorbed carbon monoxide molecule to form carbon dioxide. Using spectroscopy they could follow the consumption of carbon monoxide at the dual site.

"This particular site is specific for causing the activation of the oxygen molecule to produce an oxidation reaction on the surface of the catalyst," Yates said. "It's a new class of reactive site not identified before."