Snapshots of laser driven electrons

Physicists of the Laboratory of Attosecond Physics at the Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics succeeded in the first real-time observation of laser produced electron plasma waves and electron bunches accelerated by them.

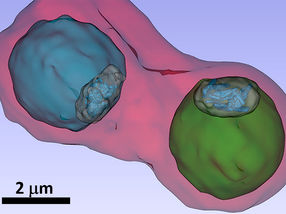

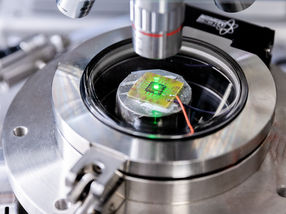

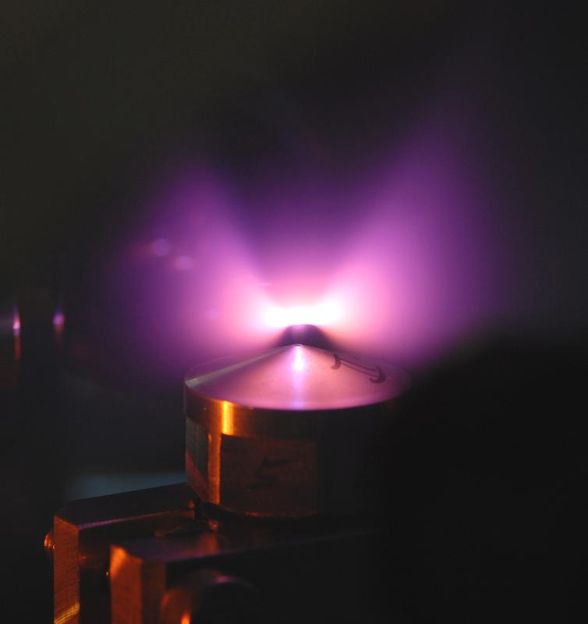

Helium atoms flowing from a small nozzle are ionized by a laser pulse. Thereby a plasma channel forms from helium ions and free electrons. In this channel the flash of light accelerates a small portion of the electrons almost to the speed of light.

Thorsten Naeser

Flocking behavior does not only exist among birds, insects or fish; the microcosm offers similar phenomena, too. A team of scientists including Ferenc Krausz and his employees Laszlo Veisz and Alexander Buck of the Laboratory of Attosecond Physics (LAP) at the Max-Planck-Institut für Quantenoptik (MPQ) and the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität (LMU Munich), in cooperation with colleagues from the Friedrich Schiller University Jena, succeeded in the first observation of laser-accelerated fast electron swarms in conjunction with a plasma wave consisting of positively charged helium ions and slow background electrons.

This way, the physicists managed to observe in real-time how electrons form bunches under the influence of strong laser pulses and how they behave in the slipstream during their flight. The findings facilitate the development of new electron and light sources with which, for example, the structure of atoms and molecules can be explored. In medicine, this knowledge helps the development of new X-ray sources whose resolution will be much higher than current devices allow.

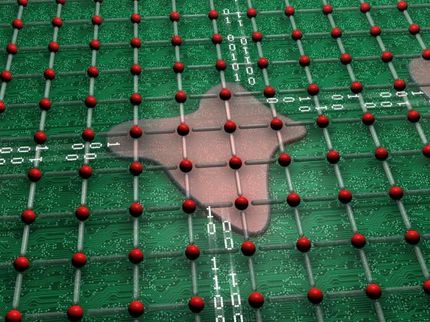

When short laser pulses irradiate e.g. helium atoms their structure is heavily disturbed. If the light is strong enough, electrons are pulled out of the atoms and the helium atoms become ions. This mixture of electrons and ions is called plasma which may support wave structures –the so called electron plasma waves– when exposed to strong light. In laser physics this process and these waves are used under special conditions to rapidly accelerate a small number of the electrons to close to the speed of light and to control them.

A team from the Laboratory of Attosecond Physics at the MPQ and the LMU Munich, in cooperation with the Friedrich Schiller University Jena, succeeded in taking snapshots of both the accelerated electron bunches and the plasma wave produced by the strong laser light that drives them.

In their experiments, the laser physicists focused a laser pulse on a helium gas jet (or flow of helium gas) from a specially designed nozzle. The pulse only lasts a few femtoseconds (one femtosecond corresponds to millionth of a billionth second, 10-15 seconds). The flash of light consists of only a few wave cycles and around one billion billion light particles (photons). Its highest power is focused to a very short moment - the duration of the flash of light - and a tiny area. The high-intensity laser pulse tears out all the electrons from the atoms, leaving behind a plasma composed of free electrons and Helium nuclei. In this cocktail the electrons are much lighter than the helium ions; as a result they are pushed aside. While the laser pulse sweeps across the system the ions remain stationary and the released electrons oscillate around one location. Together the particles form a plasma wave; one oscillation of this structure takes around 20 femtoseconds.

In the plasma wave, gigantic electric fields are formed, which are 1000 times stronger than those generated in the world’s largest particle accelerators. A small number of the electrons take advantage of these fields, fly as a swarm behind the laser pulse in its slipstream and accelerate to close to the speed of light. In this process, every accelerated electron has almost the same energy.

Physicists have long been aware of this phenomenon and it has been demonstrated in earlier experiments. The Japanese laser physicist Toshiki Tajima already described this process in 1970. Today Tajima works as a researcher in the excellence cluster Munich-Centre for Advanced Photonics. However, up to now it has only been possible to individually observe the electron swarm or the whole plasma wave with reduced resolution.

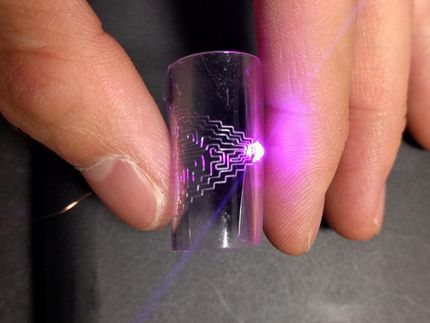

The laser physicists from Garching succeeded in recording both phenomena with a high-resolution image of the plasma wave. The process was documented in snapshots with the same light pulse also responsible for accelerating the electrons. The physicists had previously split the laser pulse so that a small portion of it illuminated the system of free electrons and ions perpendicularly to the electron beam. The periodic structure of the plasma wave refracts and partially deflects the light. ″We observe the deflection and thereby image the plasma wave as a modulation of brightness onto a camera, ″ explains Laszlo Veisz, the research-group leader of the LAP team. In doing so the researchers achieve a unique spatial and temporal resolution in the femtosecond range. The electron swarm produces strong magnetic fields that the physicists also record and thus determine its position and duration. Eventually, a film describing the acceleration of the electrons results from the combination of both measurement methods.

″The obtained improved knowledge about laser-driven electron acceleration helps us in the development of new X-ray sources of unprecedented quality, not only for basic research but also for medicine, ″ explains Ferenc Krausz.

![[Fe]-hydrogenase catalysis visualized using para-hydrogen-enhanced nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy](https://img.chemie.de/Portal/News/675fd46b9b54f_sBuG8s4sS.png?tr=w-712,h-534,cm-extract,x-0,y-16:n-xl)