Just scratching the surface: New technique maps nanomaterials as they grow

Advertisement

Researchers at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute have developed a measurement technique that will help scientists and companies map nanomaterials as they grow. The discovery could help create superior nanotechnologies and lead to the development of more efficient solar panels and increased magnetic data storage.

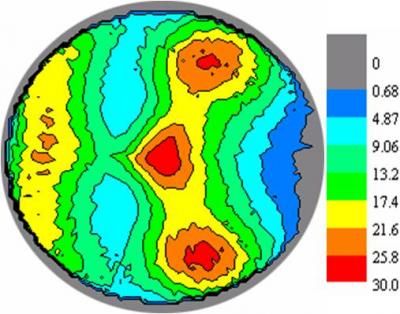

The new technique maps the surface of a nanomaterial as it grows. In this figure, a surface pole figure has been created for magnesium nanoblades.

Rensselaer/Gwo-Ching Wang

"Since we discovered this technique, we have been trying to get the word out to the nanoscience and nanotechnology research community," said professor and head of physics, applied physics, and astronomy Gwo-Ching Wang, who helped discover the technique. "It is inexpensive because it uses existing technology and vastly increases the rate of discovery by giving researchers a very clear picture of how to perfect and duplicate the growth of a new nanomaterial without spending months characterizing its structures after the growth."

The approach is based on a commonly used technique known as reflection high-energy electron diffraction, or RHEED. The traditional RHEED system creates an interference pattern of the surface of the nanomaterial. The pattern contains only partial information of the surface and is only a snapshot in time of the growing surface. The researchers modified the traditional RHEED technique by rotating the substrate on which the nanomaterial is being grown. This gives them a diagram containing the complete information on the crystal orientation distribution of the growing surface.

The new technique is different from other common techniques such as X-rays because it monitors the surface structure of the material as it grows. X-ray and other technologies measure the entire material, from the tip of the new growth straight through the substrate that the material is growing on. The new RHEED technique shows the growth of only a few nanometers of a material at a time.

"The creation of a surface crystal orientation diagram is particularly important for revealing the nature of the growth of nanostructures such as nanodots, nanorods, and nanoblades, which have strong energy and data storage capabilities, but their orientation can change dramatically over time," Wang said. These changes in crystal orientation and morphology of the material can substantially increase or decrease the material's efficiency. It also makes their use in consumer products difficult because of their unpredictability, according to Wang.

Wang views solar energy materials as one of the most important applications for the new technique. The most efficient solar panels on the market are comprised of single crystal materials, meaning that the material is one unbroken material with no grain boundaries. Grain boundaries in a nanomaterial cause huge decreases in energy-conversion capabilities. But, single crystal solar cells are so costly that they could never be widely used on the consumer market, Wang said. So, many scientists and solar cell companies are working to create polycrystalline materials that grow in such a way that they transfer light into electricity similar to a single crystal material despite having grain boundaries. These materials are also much less expensive, according to Wang.

"The problem with creating high-quality polycrystalline materials is that you need a powerful technique to monitor them in nanoscale dimensions as they grow so you can quickly work on recreating the material to maximize its efficiency," Wang said. "The new RHEED technique really allows researchers to create a material, see how it formed, and then turn around and recreate the most ideal version of that material without extensive experimentations."