New fabric coating protects your clothes, and the environment

When you spill pasta sauce on your favorite shirt but there is no trace of it after being washed, you can thank oleophobicity, a resistance to oil commonly applied to textiles.

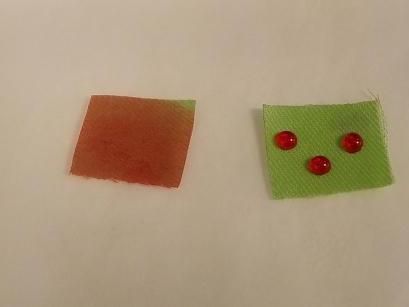

Samples of cloth both untreated, left, and treated with a fluorine-free oleophobic coating.

Genggeng Qi, Cornell University

That resistance, however, comes at a price. The coating that makes textiles oil resistant is fluorine-based and breaks down into chlorofluorocarbon gas, a greenhouse gas harmful to the environment.

But that may change, as a result of a Cornell University cross-campus collaboration involving Emmanuel Giannelis, professor of materials science and engineering in the College of Engineering, and Jintu Fan, professor and chair of the Department of Fiber Science and Apparel Design in the College of Human Ecology. Work from their labs has yielded a promising new material - for which the pair submitted a patent disclosure to the Center for Technology Licensing (CTL) - that could help change the way oleophobicity is developed. A provisional patent for the material has been filed by CTL, according to Giannelis.

Fan was excited about the partnership, noting that engineers don't always lend their expertise to the fashion industry.

"In general, collaboration with the engineering department is very interesting and fruitful," he said. "They are very good and bring a lot of wonderful ideas. But maybe in the past they were not targeting the textile and fashion industry, which is a $3 trillion a year industry."

At the time of his seminar, Giannelis and his group were working on super-hydrophilic polymeric membranes that are used in water purification, and Fan asked if they could team up and "basically apply some of the work that we were doing in polymeric membranes to textiles," Giannelis said.

They worked with an apparel maker on creating a polymer that could make fabric more breathable while retaining wrinkle resistance - always a challenge - and Giannelis said they made good progress along that line.

"The company came back and said, 'That is good and great - but can you do something similar with oleophobic coatings?'" he said. "It's a very different kind of chemistry, and something we had not worked on previously, but one of the great things about being at Cornell is that we have great students and postdocs who can take this kind of challenge and do great things."

Postdoctoral researcher Genggeng Qi developed a polymer that combines well-known chemistry with a rough surface texture that creates little air pockets. Fluids with a high enough surface tension will ball up on this fiber and not stick, making for easy cleaning.

This roughness uses the same principle as the water-resistant quality of the lotus leaf, which has a rough nanostructure and naturally repels water.

Fan is excited by early results of this material, noting that they've just done testing using mineral oil, which has a low surface tension.

"We've found that even after 30 washings, it's still durable, which is great," he said. "Even if we can achieve [oleophobicity] even close to fluorine-based [polymers], that would be a huge breakthrough."

Giannelis is cautiously optimistic about the work.

"I don't want to declare complete victory," he said with a smile, "but we believe we are the first group to show that non-fluorine-based chemistry opens up the possibility to create oleophobic coatings that are probably good enough to resist stains from vegetable oils, olive oil, and other oils.

"For industrial applications ... we're not quite there yet,' he added.

"But we believe that we've opened up an opportunity, and more work will get us there."