Transparent ceramics

Scientists synthesise first sample of transparent silicon nitride

Scientists have synthesised the first transparent sample of a popular industrial ceramic at DESY. The result is a super-hard window made of cubic silicon nitride that can potentially be used under extreme conditions like in engines, as the Japanese-German team writes in the journal Scientific Reports. Cubic silicon nitride (c-Si3N4) forms under high pressure and is the second hardest transparent nanoceramic after diamond but can withstand substantially higher temperatures.

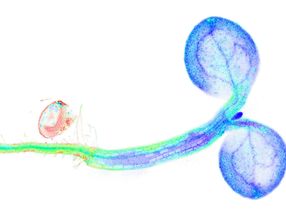

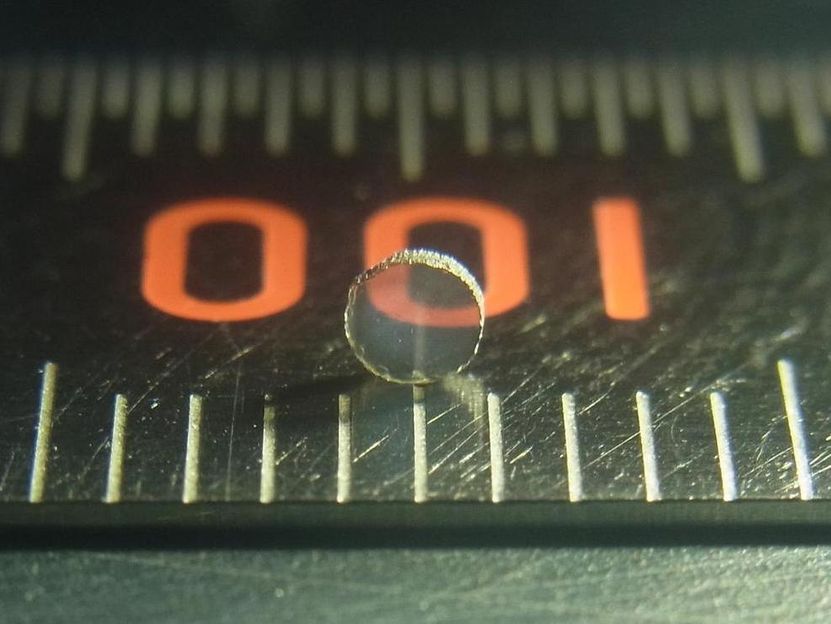

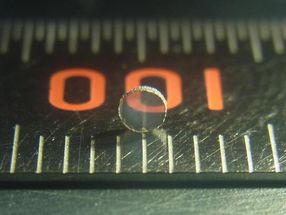

A sample of transparent polycrystalline cubic silicon nitride, synthesised at DESY.

Norimasa Nishiyama, DESY/Tokyo Tech

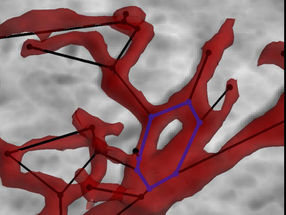

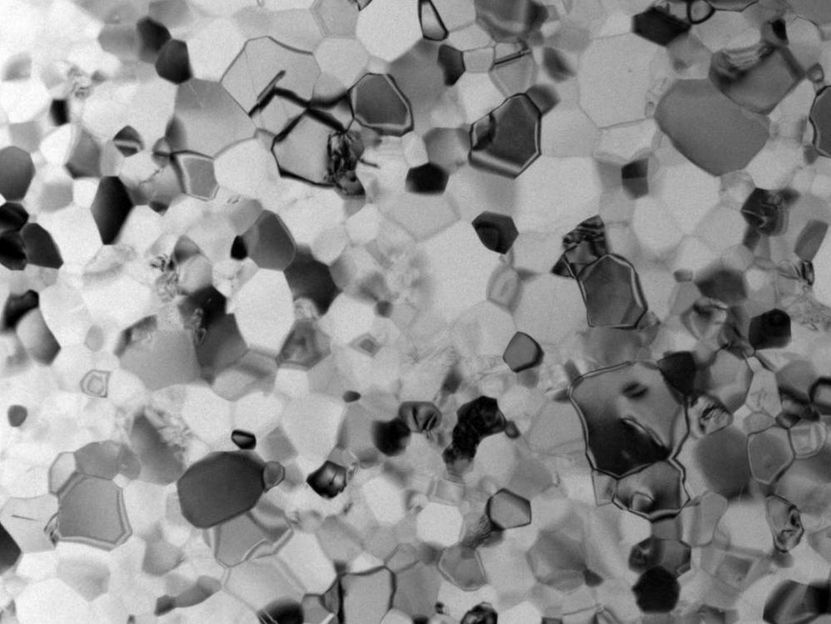

A bright-field transmission electron microscope image of cubic silicon nitride. The average grain size is about 150 nanometres (millionths of a millimetre).

Norimasa Nishiyama, DESY/Tokyo Tech

“Silicon nitride is a very popular ceramic in industry,” explains lead author Dr. Norimasa Nishiyama from DESY who now is an associate professor at Tokyo Institute of Technology. “It is mainly used for ball bearings, cutting tools and engine parts in automotive and aircraft industry.” The ceramic is extremely stable, because the silicon nitrogen bond is very strong. At ambient pressures, silicon nitride has a hexagonal crystal structure and sintered ceramic of this phase is opaque. Sintering is the process of forming macroscopic structures from grain material using heat and pressure. The technique is widely used in industry for a broad range of products from ceramic bearings to artificial teeth.

At pressures above 130 thousand times the atmospheric pressure, silicon nitride transforms into a crystal structure with cubic symmetry that experts call spinel-type in reference to the structure of a popular gemstone. Artificial spinel (MgAl2O4) is widely used as transparent ceramic in industry. “The cubic phase of silicon nitride was first synthesised by a research group at Technical University of Darmstadt in 1999, but knowledge of this material is very limited,” says Nishiyama. His team used a large volume press (LVP) at DESY to expose hexagonal silicon nitride to high pressures and temperatures. At approximately 156 thousand times the atmospheric pressure (15.6 gigapascals) and a temperature of 1800 degrees Celsius a transparent piece of cubic silicon nitride formed with a diameter of about two millimetres. “It is the first transparent sample of this material,” emphasises Nishiyama.

Analysis of the crystal structure at DESY's X-ray light source PETRA III showed that the silicon nitride had completely transformed into the cubic phase. “The transformation is similar to carbon that also has a hexagonal crystal structure at ambient conditions and transforms into a transparent cubic phase called diamond at high pressures,” explains Nishiyama. “However, the transparency of silicon nitride strongly depends on the grain boundaries. The opaqueness arises from gaps and pores between the grains.”

Investigations with a scanning transmission electron microscope at the University of Tokyo showed that the high-pressure sample has only very thin grain boundaries. “Also, in the high-pressure phase oxygen impurities are distributed throughout the material and do not accumulate at the grain boundaries like in the low-pressure phase. That's crucial for the transparency,” says Nishiyama.

“Cubic silicon nitride is the hardest and toughest transparent spinel ceramic ever made,” summarises Nishiyama. The scientists foresee diverse industrial applications for their super-hard windows. “Cubic silicon nitride is the third hardest ceramic known, after diamond and cubic boron nitride,” explains Nishiyama. “But boron compounds are not transparent, and diamond is only stable up to approximately 750 degrees Celsius in air. Cubic silicon nitride is transparent and stable up to 1400 degrees Celsius.”

However, because of the large pressure needed to synthesise transparent cubic silicon nitride, the possible window size is limited for practical reasons. “The raw material is cheap, but to produce macroscopic transparent samples we need approximately twice the pressure as for artificial diamonds,” says Nishiyama. “It is relatively easy to make windows with diameters of one to five millimetres. But it will be hard to reach anything over one centimetre.”

Tokyo Institute of Technology, Ehime University, the University of Bayreuth, Japanese National Institute for Materials Science, and Hirosaki University were also involved in this research.