Synthetic chemicals: Ignored agents of global change

Despite a steady rise in the manufacture and release of synthetic chemicals, research on the ecological effects of pharmaceuticals, pesticides, and industrial chemicals is severely lacking. This blind spot undermines efforts to address global change and achieve sustainability goals. So reports a new study in Frontiers in ecology and the Environment.

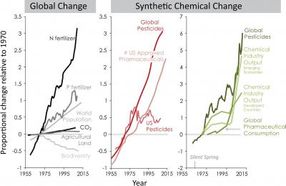

(a) Trajectories for drivers of global environmental change as defined by the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA 2005); (b) increases in the diversity of US pharmaceuticals and the application of pesticides within the US and globally; (c) trends for the global trade value of synthetic chemicals and for the pesticide and pharmaceutical chemical sectors individually, used as a proxy for the mass of chemicals produced in the absence of national or international estimates of the amounts of pharmaceuticals and chemicals produced. All trends are shown relative to values reported in 1970, with the exception of pharmaceutical consumption, where the earliest data reported are from 1975.

© The Ecological Society of America

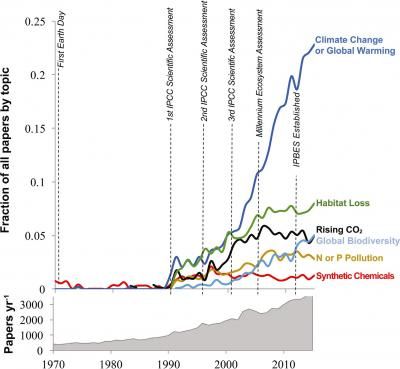

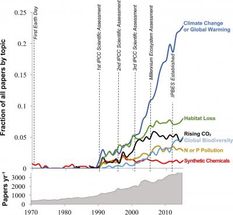

Total publications and the proportion of published papers including global-change driver terms in the top 20 ecology journals according to the highest total citations reported in the ecology section of the ISI Web of Science for the period 1970- 2015.

© The Ecological Society of America

Emma J. Rosi , a freshwater ecologist at the Cary Institute and a co-author on the paper, explains, "To date, global change assessments have ignored synthetic chemical pollution. Yet these chemicals are increasing at a rate that is on par, or more rapid, than other agents of global change, such as CO2 emissions or nutrient pollution."

The study's team assessed global trends in synthetic chemical pollution since the 1970s and compared results to other drivers of global change. Then they surveyed leading ecological journals, U.S. ecological meeting presentations, and National Science Foundation grants for research on synthetic chemicals. Less than 1% of the journal articles, 1.3% of the presentations, and 0.01% of the NSF grants explored the environmental effects or fate of these chemicals.

Author Emily S. Bernhardt , professor of biogeochemistry at Duke's Nicholas School of the Environment, comments, "Research on the ecological impacts of synthetic chemical pollution has been static since the 1970s. But our portfolio of these manufactured chemicals keeps growing - with more than 80,000 now in use commercially. This knowledge gap is becoming a chasm, with real consequences for ecological health."

Synthetic chemicals meet the criteria set out by the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment to define agents of global change: they are globally distributed, they increase in relation to human populations and economic growth, and they have known impacts on organisms. Yet they have largely remained below the radar of global assessments.

Pesticides, pharmaceuticals, and industrial chemicals can leave long-term toxic legacies that ripple through ecosystems. Traditional ecotoxicology, done in laboratory settings on individual chemicals, bears little resemblance to the behavior of these compounds in nature. Some accumulate in food webs; others become more toxic due to reactions with chemicals already in the environment or through transformations by organisms or sunlight.

Co-author Mark O. Gessner of Germany's Leibniz Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries (IGB) explains, "Identifying the environmental threat of synthetic chemicals as a whole relies on new concepts and greatly intensified research. At present there is grossly insufficient information to assess the environmental impact of the wide variety of synthetic chemicals in use today, particularly when it comes to effects at a large scale and in the long run."

The study's results reveal that the National Science Foundation, the primary funding agency for U.S. ecological research, is not supporting ecological research on synthetic chemicals. Compounding the problem - other U.S. government agencies and private foundations that once funded long term field research on these contaminants have had their budgets cut, or have redirected their funding streams to human health and lab-based studies that fall short of capturing natural complexity.

Among the paper's recommendations: accelerating synthetic chemical impact research by mobilizing increased funding, fostering collaboration among ecologists and ecotoxicologists to better predict and reduce environmental harm by synthetic chemicals, and launching an internationally-coordinated effort to assess how synthetic chemical pollution impacts the goals and targets of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the Intergovernmental Panel on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Rosi concludes, "In the 1960s, Rachel Carson's Silent Spring sounded the alarm on the environmental dangers of synthetic chemicals. The problem hasn't gone away, it's only intensified, and we need to reawaken awareness. Synthetic chemicals are leading agents of global change and it's essential that we invest in the research needed to understand and minimize their impacts."