Researchers develop DNA-based single-electron electronic devices

Nature has inspired generations of people, offering a plethora of different materials for innovations. One such material is the molecule of the heritage, or DNA, thanks to its unique self-assembling properties. Researchers at the Nanoscience Center (NSC) of the University of Jyväskylä and BioMediTech (BMT) of the University of Tampere have now demonstrated a method to fabricate electronic devices by using DNA. The DNA itself has no part in the electrical function, but acts as a scaffold for forming a linear, pearl-necklace-like nanostructure consisting of three gold nanoparticles. The research was funded by the Academy of Finland.

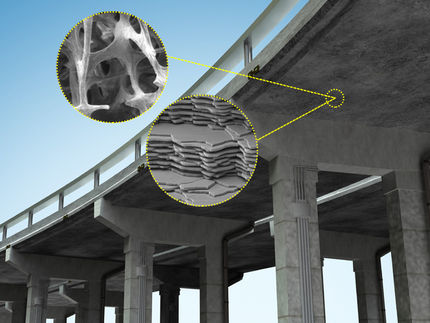

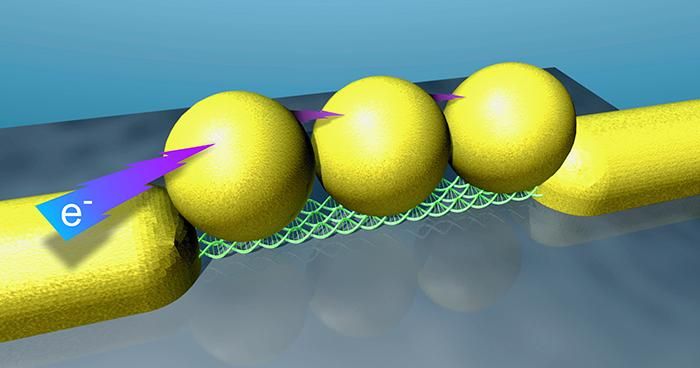

The DNA itself has no part in the electrical function, but acts as a scaffold for forming a linear, pearl-necklace-like nanostructure consisting of three gold nanoparticles.

The University of Jyväskylä

The nature of electrical conduction in nanoscale materials can differ vastly from regular, macroscale metallic structures, which have countless free electrons forming the current, thus making any effect by a single electron negligible. However, even the addition of a single electron into a nanoscale piece of metal can increase its energy enough to prevent conduction. This kind of addition of electrons usually happens via a quantum-mechanical effect called tunnelling, where electrons tunnel through an energy barrier. In this study, the electrons tunnelled from the electrode connected to a voltage source, to the first nanoparticle and onwards to the next particle and so on, through the gaps between them.

"Such single-electron devices have been fabricated within the scale of tens of nanometres by using conventional micro- and nanofabrication methods for more than two decades," says Senior Lecturer Jussi Toppari from the NSC. Toppari has studied these structures already in his PhD work.

"The weakness of these structures has been the cryogenic temperatures needed for them to work. Usually, the operation temperature of these devices scales up as the size of the components decreases. Our ultimate aim is to have the devices working at room temperature, which is hardly possible for conventional nanofabrication methods - so new venues need to be found."

Modern nanotechnology provides tools to fabricate metallic nanoparticles with the size of only a few nanometres. Single-electron devices fabricated from these metallic nanoparticles could function all the way up to room temperature. The NSC has long experience of fabricating such nanoparticles.

"After fabrication, the nanoparticles float in an aqueous solution and need to be organised into the desired form and connected to the auxiliary circuitry," explains researcher Kosti Tapio. "DNA-based self-assembly together with its ability to be linked with nanoparticles offer a very suitable toolkit for this purpose."

Gold nanoparticles are attached directly within the aqueous solution onto a DNA structure designed and previously tested by the involved groups. The whole process is based on DNA self-assembly, and yields countless of structures within a single patch. Ready structures are further trapped for measurements by electric fields.

"The superior self-assembly properties of the DNA, together with its mature fabrication and modification techniques, offer a vast variety of possibilities," says Associate Professor Vesa Hytönen.

Electrical measurements carried out in this study demonstrated for the first time that these scalable fabrication methods based on DNA self-assembly can be efficiently utilised to fabricate single-electron devices that work at room temperature.

Original publication

Other news from the department science

These products might interest you

NANOPHOX CS by Sympatec

Particle size analysis in the nano range: Analyzing high concentrations with ease

Reliable results without time-consuming sample preparation

Eclipse by Wyatt Technology

FFF-MALS system for separation and characterization of macromolecules and nanoparticles

The latest and most innovative FFF system designed for highest usability, robustness and data quality

DynaPro Plate Reader III by Wyatt Technology

Screening of biopharmaceuticals and proteins with high-throughput dynamic light scattering (DLS)

Efficiently characterize your sample quality and stability from lead discovery to quality control

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.