UW Professor Emeritus David Thouless wins Nobel Prize for exploring exotic states of matter

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences announced that David James Thouless, professor emeritus at the University of Washington, will share the 2016 Nobel prize in physics with two of his colleagues.

This is David Thouless on May 3, 1995, on his election to the US National Academy of Sciences.

Mary Levin/University of Washington

Thouless splits the prize with Professor F. Duncan M. Haldane of Princeton University and Professor J. Michael Kosterlitz of Brown University "for theoretical discoveries of topological phase transitions and topological phases of matter," according to the prize announcement from the Academy. Half the prize goes to Thouless while Haldane and Kosterlitz divide the remaining half. Thouless is the UW's seventh Nobel laureate, and second in physics after Hans Dehmelt in 1989.

"Prof. Thouless' work is a perfect example of why curiosity-driven basic science is so vital," said UW President Ana Mari Cauce. "Not only did his discoveries open up entirely new fields of research, but they also have had implications for the electronic devices that power our world today and those that may do so in the future -- everything from advanced superconductors to quantum computers to other applications we can hardly imagine. We are tremendously proud of this recognition of the seminal importance of his work."

Born in 1934 in Bearsden, Scotland, Thouless earned his undergraduate degree in 1955 from Cambridge University and a doctorate degree in 1958 from Cornell University, where he studied under physicist and Nobel laureate Hans Bethe. Thouless was a postdoctoral researcher at the University of California, Berkeley, before returning to the United Kingdom to work with world-renowned physicist Rudolf Peierls at the University of Birmingham.

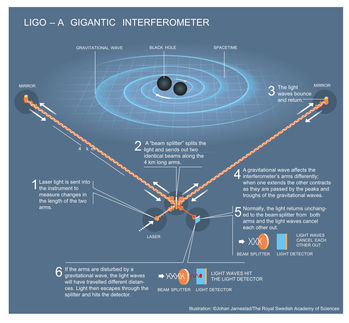

At Birmingham, where he was a professor of mathematical physics from 1965 to 1978, Thouless began a pivotal collaboration with Kosterlitz which overturned prevailing theories on how matter behaves in flat, two-dimensional environments. As the Nobel announcement explains they and Haldane discovered that, in these extreme "flatland" settings, matter exhibits properties explained only using complex topological methods.

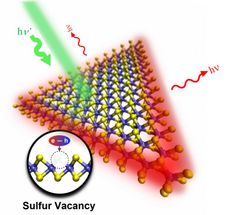

Topology is the branch of mathematics dealing with properties that change in a stepwise fashion. And it turns out that the promise of new materials and methods for manipulating matter lie within these "flatlands," where quantum mechanics is exposed and matter assumes more "exotic" states than the typical solid, liquid or gas. Their theories and practices have revealed new ways to understand physical interactions in this "exotic" state.

All matter rests on a bed made by the rules of quantum mechanics. Larger and bulkier forces like gravity often obscure these quantum-level interactions -- just as a sturdy mattress, fluffy pillows and thick quilts obscure the underlying bedframe. But that frame is still there, and forms the foundation of the larger, overlaying structure.

In the flattened, 2-D realm of their investigations, these scientists were able to describe new and unique behaviors of physical matter under these conditions.

"It is the foundation for new technologies we are exploring today, using 2-D surfaces using graphene and other 'new materials,'" said Marcel Den Nijs, a UW professor of physics who has known Thouless for 35 years. "This award was a long time coming. He's a brilliant scientist and wonderful person."

In work beginning in the 1970s, Thouless and Kosterlitz showed how matter in the flatlands can transition between phases, and does so using fundamentally different interactions than in our more familiar 3-D realm.

After a brief stint at Yale University, Thouless moved to the UW physics department in 1980 and used topological methods to explain what physicists call the quantum Hall effect. This phenomenon was described in a pioneering experiment by physicist and Nobel laureate Klaus von Klitzing, but could not be explained using theories at the time.

Thouless used topological methods to explain von Klitzing's results, showing that quantum mechanics reigned supreme in the flatlands. He did this work with three UW postdoctoral researchers, including Den Nijs.

These lines of research set the stage for today's quests in physics and materials sciences for innovative approaches to electronics and computing. They all depend on a thorough understanding of topological interactions in flat, 2-D realms. In other words, today's materials and computers make use of quilts and pillows on the bed, while tomorrow's will exploit the bedframe itself.

"There is no greater honor for a physicist and scholar than winning the Nobel Prize," said Robert Stacey, Dean of the UW College of Arts & Sciences. "We are thrilled and deeply honored to celebrate Professor Thouless' lifetime contributions to his field. His work epitomizes the University of Washington's deep commitment to world-class research that stretches our understanding of exotic matter and the complex universe around us. And it reminds us how important fundamental scientific research and education are to our society, even when the practical applications of such research take decades to emerge."

Thouless has received many awards and honors for his groundbreaking discoveries. He became a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1979 and, in 1981, a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. In 1987, he became a Fellow of the American Physical Society and earned the prestigious Wolf Prize for Physics in 1990. Thouless retired from the UW in 2003. Thouless' wife Margaret was an associate professor of pathobiology at the UW from 1980 to 2004.