Some like it hot: Simulating single particle excitations

plasmons, which may be thought of as clouds of electrons that oscillate within a metal nanocluster, could serve as antennae to absorb sunlight more efficiently than semiconductors. Understanding and manipulating them is important for their potential use in photovoltaics, solar cell water splitting, and sunlight-induced fuel production from CO2.

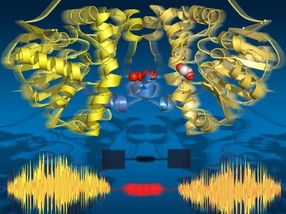

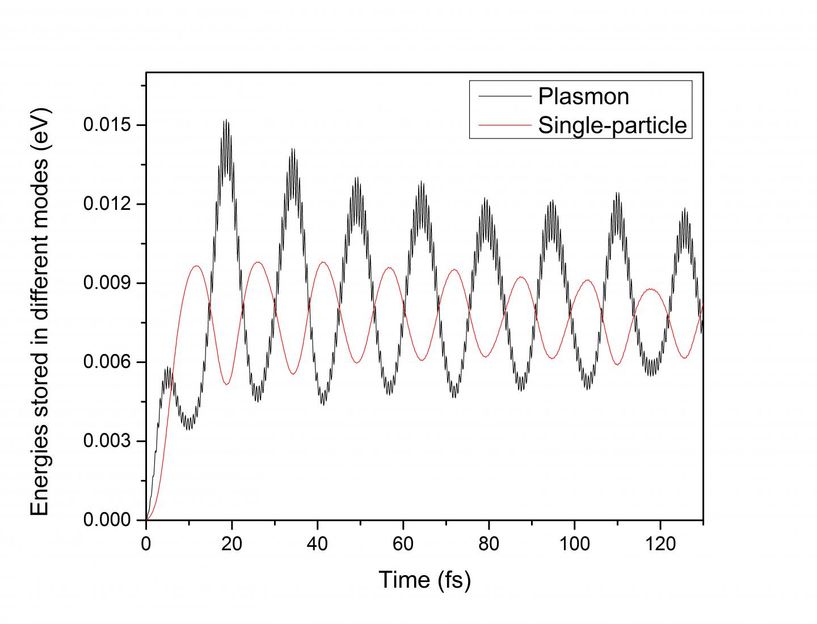

The energy stored in the plasmon and the single particle (hot carrier), when the single particle excitation energy is not in tune with the plasmon excitation energy. The oscillation between these two modes of excitation is called Rabi oscillation.

Berkeley Lab

But in these applications, single particle excitation rather than the collective plasmon excitation is needed to transfer electrons one at a time to an electrode and induce desired chemical reactions. After the plasmon is excited by sunlight, it induces the single particle excitation 'hot carriers.' Now, for the first time, the interplay between the plasmon mode and the single particle excitation within a small metal cluster has been simulated directly.

Researchers with the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) used a real-time numerical algorithm, developed at Berkeley Lab in February, to study both the plasmon and hot carrier within the same framework. That is critical for understanding how long a particle stays excited, and whether there is energy backflow from hot carrier to plasmon. The new study shows the electron movement when it is perturbed by light.

"You need to consider how the plasmon can give its energy to single particle excitations. People have done this analytically, but they looked at the bulk-like material and treated the plasmon mode using classical description," says Lin-Wang Wang, senior staff scientist at Berkeley Lab, who led this work. "We have described both the plasmon and the single particle excitation quantum mechanically, and studied nanoparticles because they are often used in actual applications. If you generate a hot carrier in such a nanosystem, it's easier to transfer to the connected electrode due to their small sizes." His calculations used light to excite Ag55, a metallic nanocluster with known geometry, and showed the behavior of the plasmon and the single particle excitation.

In the simulations, metallic nanoparticle clusters clearly responded to external light, with charge 'sloshing' back and forth within the clusters. However, that movement can be caused both by a plasmon and by single particle excitations. The trick is showing which is which.

"We found a way to distinguish them by their different oscillating behaviors. Using this method, we found that if a hot carrier excitation is in tune with the plasmon oscillation, then 90% of the plasmon energy can be converted to the single particle energy. But if they are out of tune, the total energy will go back and forth between the plasmon and the single particle exication," explains Wang.

Jie Ma, a postdoc who is the lead author of the paper, adds that "the single particle excitation is the continuous change of the electron occupation, but the plasmon is the oscillation of the electron occupations around the Fermi energy ['ground' level of the electron reservoir]." When resonance builds up between the two, most of the energy transfers to the hot carrier.

Conventional ground state computational methods cannot be used to study systems in which electrons have been excited. But using real-time simulations, an excited system can be modeled with time-dependent equations that describe the movement of electrons in the femtosecond (quadrillionth of a second) timescale.

An excited single particle can drop rapidly to a lower energy state by emitting a phonon, which is the vibration of the atoms. This means that it is no longer a hot carrier. Eventually, all hot carriers will lose their energy, as electrons and holes recombine in a metallic system. But the question is how long the hot carrier will remain hot and able to transport to another electrode or molecule before it is cooled. Previous studies, which do not include the nuclei movement, cannot describe the cooling process. But Wang's simulation suggests that in a small nanostructure the carrier cools more slowly than in a bulk system.

"Here, we simulated isolated nanoparticles. But if you put the nanoparticles on some substrate, that could be really interesting," says Ma. It will be important to understand how long a hot carrier can stay hot.

With powerful computational tools, these questions can now be answered and used in the development of future plasmon-driven applications.