New cool phase of superionic ice

Scientists have predicted a new phase of superionic ice, a special form of ice that could exist on Uranus and Neptune, in a theoretical study performed by a team of researchers at Princeton University.

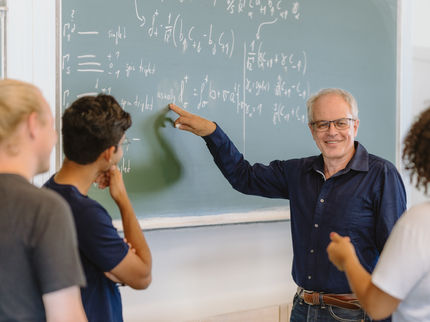

"Superionic ice is this in-between state of matter that we can't really relate to anything we know of -- that's why it's interesting," Salvatore Torquato, a Professor of Chemistry who jointly led the work with Roberto Car, the Ralph W. '31 Dornte Professor in Chemistry. Unlike water or regular ice, in superionic ice the water molecules dissociate into charged atoms called ions, with the oxygen ions locked in a solid lattice, while the hydrogen ions move like the molecules in a liquid.

The research revealed an entirely new type of superionic ice that they call the P21/c-SI phase, which occurs at pressures even higher than in the interior of giant ice planets of our solar system. Two other phases of superionic ice thought to exist on the planets are body centered cubic superionic ice (BCC-SI) and, close-packed superionic ice (CP-SI).

Each phase has a unique arrangement of oxygen ions that gives rise to distinct properties. For example, each of the phases allows hydrogen ions to flow in a characteristic way. The effects of this ionic conductivity could be observed by planetary scientists in search of superionic ice. "These unique properties could essentially be used as signatures of superionic ice," said Torquato, "so now that you know what to look for, you have a better chance of finding it."

Unlike Earth, which has two magnetic poles (north and south), ice giants can have many local magnetic poles, which leading theories suggest may be due to superionic ice and ionic water in the mantle of these planets. In ionic water both oxygen and hydrogen ions show liquid-like behavior. Scientists have proposed that heat emanating outward from the planet's core may pass through an inner layer of superionic ice, and through convection, create vortices on the outer layer of ionic water that give rise to local magnetic fields.

By using theoretical simulations, the researchers were able to model states of superionic ice that would be difficult to study experimentally. They simulated pressures that were beyond the highest possible pressures attainable in the laboratory with instruments called diamond anvil cells. Extreme pressure can be achieved through shockwave experiments but these rely on creating an explosion and are difficult to interpret, Professor Car explained.

The researchers calculated the ionic conductivity of each phase of superionic ice and found unusual behavior at the transition where the low temperature crystal, in which both oxygen and hydrogen ions are locked together, transforms into superionic ice. In known superionic materials, generally the conductivity can change either abruptly (type I) or gradually (type II), but the type of change will be specific to the material. However, superionic ice breaks from convention, as the conductivity changes abruptly with temperature across the crystal to close-packed superionic transition and continuously at the crystal to P21/c-SI transition.

As a foundational study, the research team investigated superionic ice treating the ions as if they were classical particles, but in future studies they plan to take quantum effects into account to further understand the properties of the material.

Original publication

Other news from the department science

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.

Most read news

More news from our other portals

Last viewed contents

Glucose_tolerance_test

Open_hearth_furnace

Steven_V._Ley

Category:Halogen-containing_alkaloids

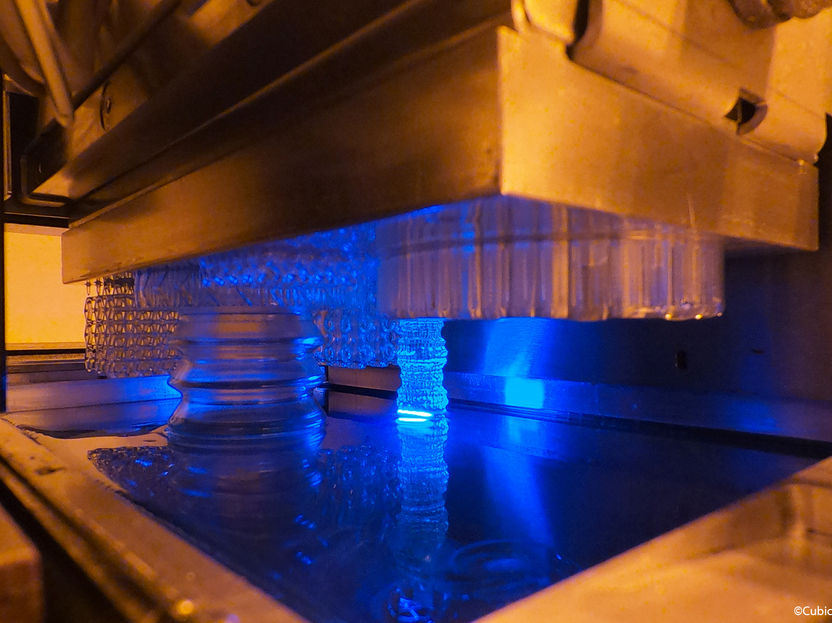

Evonik and start-up Cubicure cooperate in the field of 3D printing - Development of custom-made specialty chemical components for the next generation of materials

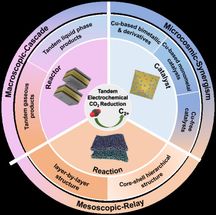

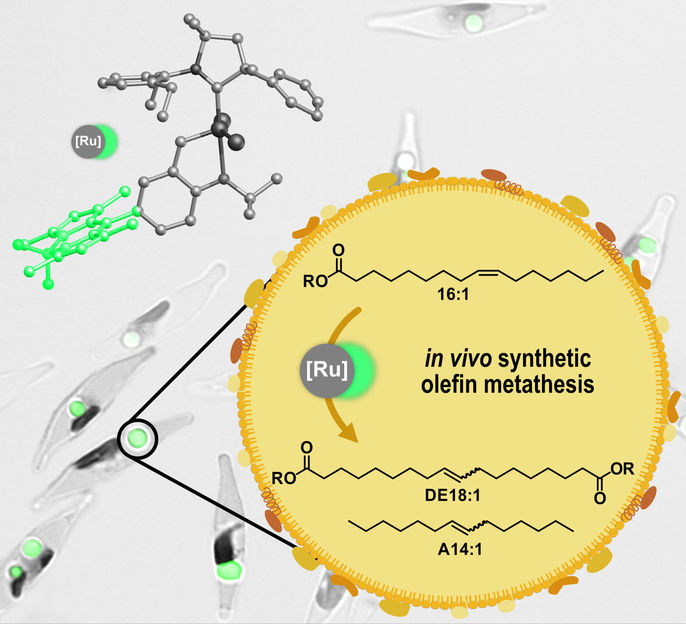

Algae as microscopic biorefineries - Chemist succeeds in taking a key step towards the production of sustainable chemicals in living microfactories

Dicoronylene

Filter_(oil)

Reannealing

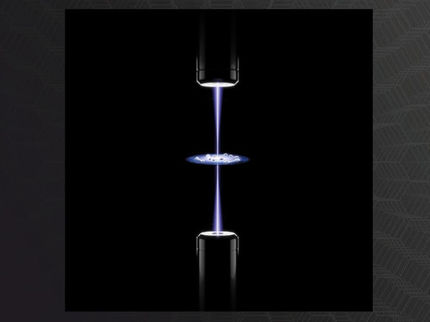

A molecule that looks like a toy top can serve as a motor for nanoscale components

In line with the 17 Sustainable Development Goals: digital 5th ECP with over 1,200 partnerings - In more than 1,200 online partnering conversations as well as numerous flash sessions, the traditional spirit of the largest speed dating event of the European chemical industry came alive again