A 'hot' new development for ultracold magnetic sensors

magnetoencephalography, or MEG, is a non-invasive technique for investigating human brain activity for surgical planning or research. It's just one of the many powerful technologies made possible by a tiny device called a SQUID, short for superconducting quantum interference device. SQUIDs can detect minuscule magnetic fields, useful in applications ranging from medical imaging of soft tissue to oil prospecting.

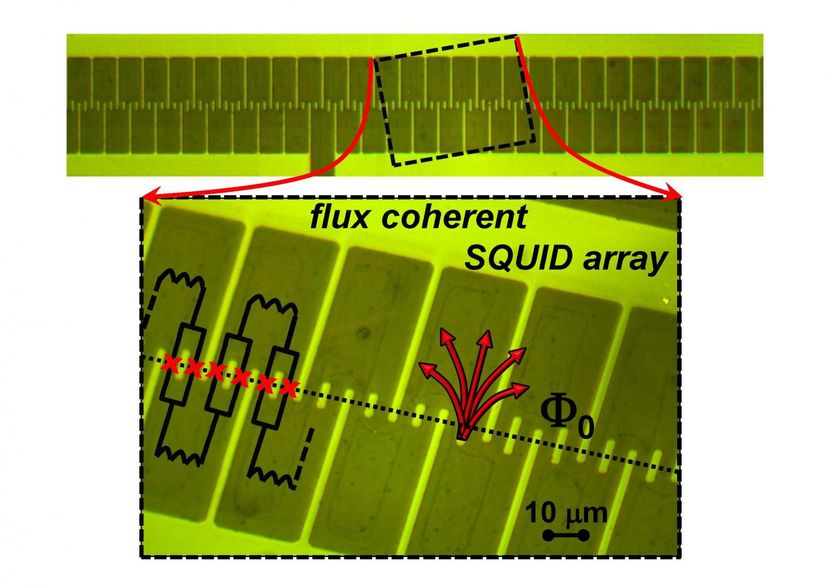

This image shows an optical micro-picture of a small part of a 484 series SQUID array showing 54 SQUIDs and a high resolution picture showing only 11 SQUIDs. The array is fabricated by optical lithography after depositing a YBa2Cu3O7 thin film on a SrTiO3 bicrystal. Each SQUID consists of two Josephson junctions connected in parallel. The Josephson junctions (schematically represented as red crosses) can be seen as 3 micron-wide narrow bridges crossing the bicrystal boundary shown with a dotted line. Each pair of successive SQUIDs is connected in series via inductive large area narrow flux-focusers (one is highlighted with a red U-shape). The flux inside each SQUID hole is quantized. Flux coherency in the array is reached when each SQUID hole is penetrated by the same number of integers of flux quanta.

Boris Chesca / Loughborough University

The most sensitive commercial magnetic sensors require a single SQUID kept at 4.2 Kelvin. Now researchers from Loughborough University and Nottingham University, have built a multi-SQUID device that can operate at 77 K - the boiling temperature of liquid nitrogen, a much cheaper coolant. The new device still outperforms most standard 4.2 K SQUID magnetometers.

"We believe there should be an immediate interest in the entire SQUID community for the potential replacement of their existing superconducting magnetic sensors based on single SQUIDs operating at 4.2 K with our SQUID arrays operating at 77 K," said Boris Chesca, a physicist at Loughborough University.

Chesca and his colleagues achieved their breakthrough high temperature SQUID performance by taking advantage of strength in numbers. While low temperature SQUIDs are inherently more sensitive, a large array of high temperature SQUIDs could theoretically achieve the same performance as a single low temperature one.

SQUIDs work by converting a measure of magnetic intensity called flux into a voltage. If you string together a series of SQUIDs the voltage output scales in direct proportion to the number of SQUIDs, while the noise in the measurement only increases as a square root of the SQUID count. Therefore, the more SQUIDs you have, the stronger the signal, and the more sensitive the measurement that can be performed.

The catch is that the approach only works if all the SQUIDs experience the same magnetic flux (a condition called flux coherency) and the interaction between each SQUID and its neighbors is minimized -- both tricky conditions to meet because of parasitic fluxes that form during normal SQUID operation. "Flux coherency could never be reached in the previous approaches in large SQUID arrays with more than 30 SQUIDs" Chesca noted.

The key difference in the array that Chesca and his colleagues designed has to do with a feature called a flux focuser. Flux focusers are large areas of superconductor that improve magnetic field sensitivity and minimize parasitic fluxes. In previous SQUID arrays, there were either no flux focusers or the flux focusers were so large that they limited the number of SQUIDs that could be integrated onto a single chip.

In the new design, the flux focusers are narrow, but long. By keeping the width of the focusers identical to the SQUIDs' width, the researchers could easily string together an arbitrarily long series of SQUIDs while still achieving a high degree of flux coherence and field sensitivity by increasing the length of the flux focusers.

Chesca and his colleagues tested the performance of their arrays (one 770 SQUIDs-long and the other 484 SQUIDs-long) and compared them to the performance of optimized low temperature single-SQUIDs operating at 4.2 K -- generally the gold standard for industrial magnetometers. They found that the new arrays' white flux noise, a key performance parameter linked to sensitivity, were superior to those of the 4.2 K SQUIDs.

"Since our SQUID arrays operate at 77 K using liquid nitrogen, they provide a magnetic sensor that is very cost effective, considering that operation of SQUIDs at 4.2K requires the use of liquid helium-4, which is much more expensive and also requires extensive training for its handling," Chesca said.