Effective conversion of methane oxidation by a new copper zeolite

Bio-inspired catalyst paves the way to 'gas-to-liquid'-technologies

A new bio-inspired zeolite catalyst, developed by an international team with researchers from Technische Universität München (TUM), Eindhoven University of Technology and University of Amsterdam, might pave the way to small scale 'gas-to-liquid' technologies converting natural gas to fuels and starting materials for the chemical industry. Investigating the mechanism of the selective Oxidation of methane to Methanol they identified a copper-oxo-cluster as the active center inside the zeolite micropores.

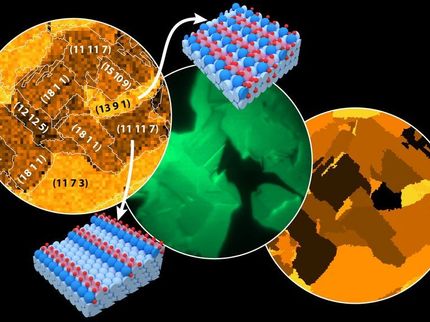

The copper atoms provide the zeolite with a bluish color.

Andreas Battenberg / TUM

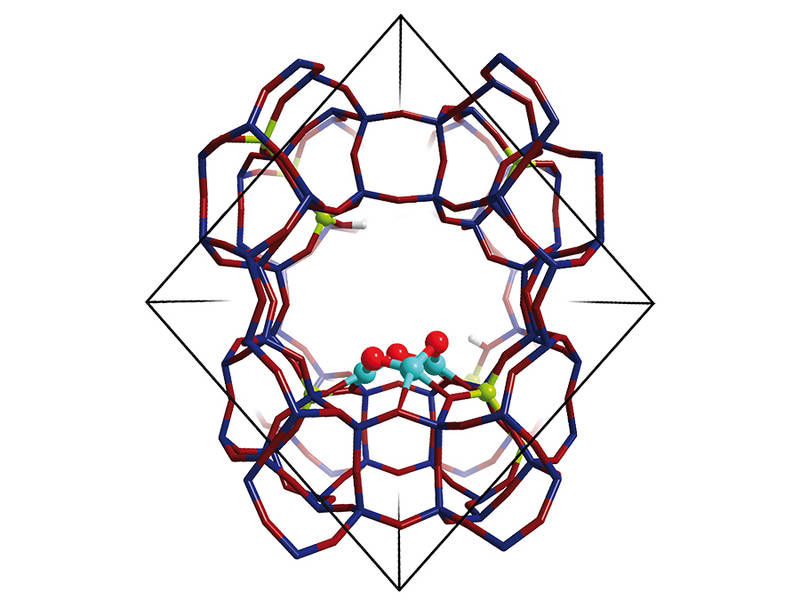

The zeolite structure with the Cu3O3-cluster as the active center (Cu: turquoise, O: red).

Guanna Li and Evgeny Pidko / TUe

In an era of depleting mineral oil resources natural gas is becoming ever more relevant, even though the gas is difficult to transport and not easily integrated in the existing industrial infrastructure. One of the solutions for this is to apply 'gas-to-liquid' technologies. These convert methane, the principal component of natural gas, to so-called synthesis gas from which subsequently methanol and hydrocarbons are produced. These liquids are then shipped to chemical plants or fuel companies all over the world.

This approach, however, today is only feasible at very large scales. Currently there is no 'gas-to-liquid' chemistry available for the economical processing of methane from smaller sources at remote locations. This has spawned many research efforts regarding the chemistry of methane conversion.

Of all the conceptually promising smaller scale processes for the direct conversion of methane, the partial oxidation to methanol seems the most viable since it allows for lower operating temperatures, making it more inherently safe and more energy efficient.

Bio-inspired catalyst

A research team combining the expertise of Moniek Tromp (UvA/HIMS), Evgeny Pidko and Emiel Hensen (Eindhoven University of Technology), Maricruz Sanches-Sanches (Technische Universität München) as well as Johannes Lercher (Technische Universität München and Pacific Northwest National Laboratory) is currently focusing on a bio-inspired method enabling such partial methane oxidation.

At the focus of the team is a modified zeolite, a highly structured porous material, developed at Lercher’s research group in Munich. This copper-exchanged zeolite with mordenite structure mimicks the reactivity of an enzyme known to efficiently and selectively oxidize methane to methanol.

In their actual publication in Nature Communications the researchers provide an unprecedented and detailed molecular insight in the way the zeolite mimics the active site of the enzyme methane monooxygenase (MMO).

Highly selective

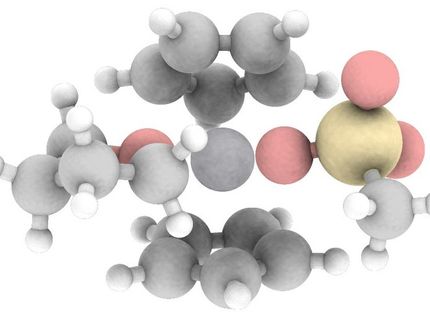

The researchers show that the micropores of the zeolite provide a perfect confined environment for the highly selective stabilization of an intermediate copper-containing trimer molecule. This result follows from the combination of kinetic studies in Munich, advanced spectroscopic analysis in Amsterdam and theoretical modeling in Eindhoven. Trinuclear copper-oxo clusters were identified that exhibit a high reactivity towards activation of carbon–hydrogen bonds in methane and its subsequent transformation to methanol.

“The developed zeolite is one of the few examples of a catalyst with well-defined active sites evenly distributed in the zeolite framework – a truly single-site heterogeneous catalyst,” says Professor Johannes Lercher. “This allows for much higher efficiencies in conversion of methane to methanol than with zeolite catalysts previously reported.”

Furthermore, the research showed the unequivocal linking of the structure of the active sites with their catalytic activity. This renders the zeolite a "more than promising" material in achieving levels of catalytic activity and selectivity comparable to enzymatic systems.