Gasoline from a nanoreactor

Researchers from the Paul Scherrer Institute (PSI) and ETH Zurich have developed a miniscule chemical reactor in the lab that could one day be used to produce gasoline and diesel more sustainable and cost-effectively than today. By specifically modifying nanometre-sized, porous zeolite crystals, the scientists built a nanoreactor that is able to complete two of the conversion steps for the production of hydrocarbons.

Researchers from the Paul Scherrer Institute and ETH Zurich have succeeded in building a miniscule chemical reactor in the lab that could one day be used to produce gasoline and diesel more cost-effectively and sustainably than today. The reactor consists of zeolite crystals that are only a few tens of nanometres in size and which the researchers modified so that they are able to perform two production steps for synthetic fuels.

Previously, each of these steps required a separate reactor. The new nanoreactor could one day help cut costs as it renders one of these two reactors redundant.

The global crude oil reserves are inevitably dwindling and the price of fuels made of the natural resource may well continue to rise in future. However, gasoline and diesel could also be produced from other raw materials. As early as 1925, German chemists Franz Fischer and Hans Tropsch devised an industrial process to produce hydrocarbons such as gasoline and diesel from syngas – a mixture of carbon monoxide and hydrogen. Originally, the idea was to obtain the syngas from coal, which is in plentiful supply in Germany. Meanwhile, natural gas primarily serves as the raw material. However, wood, sewage sludge or harvest residues could also perform this function in future.

Alternative way to make gasoline

While the Fischer-Tropsch process soared through the industrial trials, the fuel it produces is considerably more expensive than conventional gasoline obtained from crude oil. However, the cost of the method could be reduced by constructing multifunctional reactors that perform several of the conversion steps necessary. Today, each of these steps requires a separate reactor. And every reactor that needs to be built costs money, which ultimately sends the production costs sky high.

The new nanoreactor consecutively performs two of the Fischer-Tropsch process’s steps, which used to require two separate reactors. The reactor carries out the first conversion step, where many different hydrocarbons, including the components of gasoline, are produced from syngas. However, this initial step also generates undesirable hydrocarbons, which comprise longer chains of carbon atoms than the gasoline components. These long-chained hydrocarbons are found in heavy heating oil, for instance. In order to increase the concentration of superior, short-chained hydrocarbons in the end product, a second step called “cracking” is necessary. This involves breaking the long-chained molecules of the undesirable hydrocarbons into short-chained ones. This key step is also feasible in the new nanoreactor.

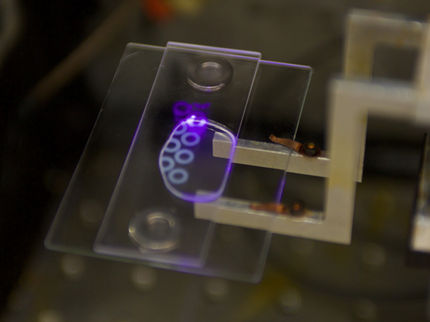

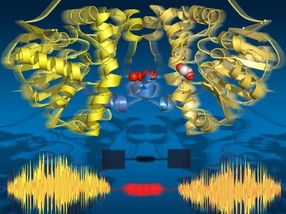

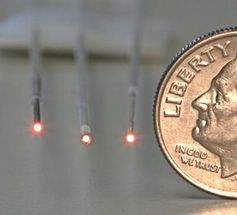

For the construction of the nanoreactor, the scientists used nanocrystals of a zeolite that they had cultivated themselves in the lab. Zeolites are materials with a crystal structure that contain tiny pores of a similar size. The pores provide a lot of surface area for the chemical reactions to take place, which results in a high yield from the reactor. As its pores have all the same size, the zeolite reactor acts as a highly selective sieve. The uniform pore size limits its product range to molecules that are small enough to pass through the pores.

Specific modifications in the lab

However, the fact that the new nanoreactor can perform two steps in the Fischer-Tropsch process is not due to the natural properties of the zeolite used, but rather specific modifications in the lab. The scientists hollowed out their nanocrystals with a caustic solution and introduced cobalt nanoparticles into the cavities created. Similar cobalt particles are used frequently in industry as catalysts, including in the Fischer-Tropsch process, where they facilitate the initial conversion step. This chemical treatment also enables the nanoreactor to carry out the cracking process: the caustic solution created places in the zeolite’s pores that behave like an acid during chemical reactions. These acidic points catalyse the breakdown, i.e. cracking, of long-chained hydrocarbons into their short-chained counterparts.

“What makes our nanoreactor so special is that two reactions which normally require two separate reactors can take place in it. Depending on how you treat the zeolite nanocrystals and which catalysts you introduce, you could use the reactor for other reactions besides the Fischer-Tropsch process, too,” says Jeroen van Bokhoven, Head of the Laboratory for Catalysis and Sustainable Chemistry at PSI and a professor at ETH Zurich.

One advantage of the new nanoreactor is that the catalyst is better protected in the cavity than in earlier versions of similar reactors. Previously, the catalyst particles would clump when the crystals were heated during the production of the reactor or during the reaction itself, which reduces the overall area of the catalyst and thus its efficacy. “These clumps don’t form in our reactor,” says van Bokhoven. This is because every catalyst particle is encased in a nanocrystal, which greatly restricts its mobility.

“This is the first ever multifunctional nanoreactor made of zeolite crystals,” says van Bokhoven. “For the first time in a reactor, we therefore combine the high yield that the porous structure of a zeolite offers with the ability to perform two reactions steps consecutively in one and the same reactor.”