Measuring the mass of 'massless' electrons

Taming graphene, Harvard-led researchers successfully measure collective mass of 'massless' electrons in motion

Individual electrons in graphene are massless, but when they move together, it's a different story. Graphene, a one-atom-thick carbon sheet, has taken the world of physics by stormin part, because its electrons behave as massless particles. Yet these electrons seem to have dual personalities. Phenomena observed in the field of graphene plasmonics suggest that when the electrons move collectively, they must exhibit mass.

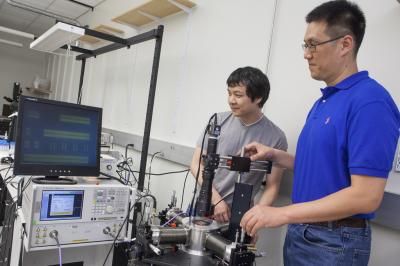

Photo by Eliza Grinnell, Harvard SEAS.

After two years of effort, researchers led by Donhee Ham, Gordon McKay Professor of Electrical Engineering and Applied Physics at the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS), and his student Hosang Yoon, Ph.D.'14, have successfully measured the collective mass of 'massless' electrons in motion in graphene.

By shedding light on the fundamental kinetic properties of electrons in graphene, this research may also provide a basis for the creation of miniaturized circuits with tiny, graphene-based components.

The results of Ham and Yoon's complex measurements, performed in collaboration with other experts at Columbia University and the National Institute for Materials Science in Japan, have been published in Nature Nanotechnology.

Without this mass, the field of graphene plasmonics cannot work, so Ham's team knew it had to be therebut until now, no one had accurately measured it.

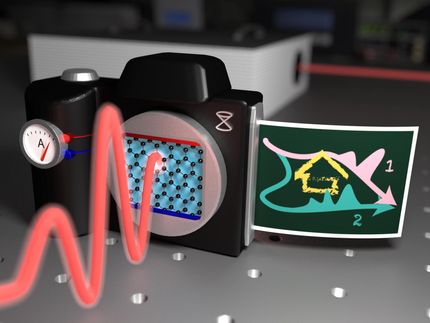

As Newton's second law dictates, a force applied to a mass must generate acceleration. Yoon and Ham knew that if they could apply an electric field to a graphene sample and measure the electrons' resulting collective acceleration, they could then use that data to calculate the collective mass.

But the graphene samples used in past experiments were replete with imperfections and impurities - places where a carbon atom was missing or had been replaced by something different. In those past experiments, electrons would accelerate but very quickly scatter as they collided with the impurities and imperfections.

"The scattering time was so short in those studies that you could never see the acceleration directly," says Ham. To overcome the scattering problem, several smart changes were necessary.

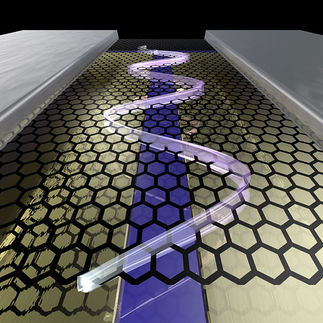

First, Ham and Yoon joined forces with Philip Kim, a physics professor at Columbia who will join the Harvard faculty on July 1 as Professor of Physics and of Applied Physics. A Harvard graduate (Ph.D. '99), Kim is well known for his pioneering fundamental studies of graphene and his expertise in fabricating high-quality graphene samples. The team was now able to reduce the number of impurities and imperfections by sandwiching the graphene between layers of hexagonal boron nitride, an insulating material with a similar atomic structure. By also collaborating with James Hone, a professor of mechanical engineering at Columbia, they designed a better way to connect electrical signal lines to the sandwiched graphene. And Yoon and Ham applied an electric field at a microwave frequency, which allows for the direct measurement of the electrons' collective acceleration in the form of a phase delay in the current.

"By doing all this, we translated the situation from completely impossible to being at the verge of either seeing the acceleration or not," says Ham. "However, the difficulty was still very daunting, and Hosang [Yoon] made it all possible by performing very fine and subtle microwave engineering and measurementsa formidable piece of experimentation."

Collective mass is a key aspect of explaining plasmonic behaviors in graphene. By demonstrating that graphene electrons exhibit a collective mass and by measuring its value accurately, Yoon says, "We think it will help people to understand and design more sophisticated plasmonic devices with graphene."