Make transition to quantum world visible

Theoretical physicist Frank Wilhelm-Mauch and his research team at Saarland University have developed a mathematical model for a type of microscopic test lab that could provide new and deeper insight into the world of quantum particles. The new test system will enable the simultaneous study of one hundred light quanta (photons) and their complex quantum mechanical relationships (“quantum entanglement”) – a far greater number than was previously possible. The researchers hope to gain new insights that will be of relevance to the development of quantum computers. They are the first group worldwide to undertake such studies using a so-called “metamaterial”.

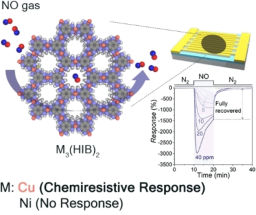

This is a specially constructed lattice of nanostructures that is able to refract light more strongly than existing natural materials.

The physical laws that apply in the macroscopic world in which we live allow us to precisely determine the location and velocity of, say, a moving car. At any one time, the car is at a particular location and is travelling at a particular speed in a particular direction. But these laws, which are at the heart of classical physics, break down when dealing with dimensions smaller than those of an atom. In this microscopic world, the (apparently counterintuitive) laws of quantum physics prevail, where a particle, such as a photon, can be simultaneously present at different locations and can be simultaneously travelling at a range of velocities. However, little is currently known about the transition zone between these “two worlds”, where the laws of classical physics end and those of quantum physics take over. “The quantum world cannot be simply mapped onto larger, precisely determinable systems,” explains Frank Wilhelm-Mauch.

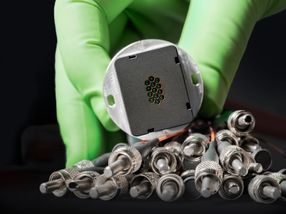

The theoretical physicist and his research group have used mathematical methods to develop a micro laboratory that is not dissimilar to a length of conventional antenna cable but that provides a controlled system with which to examine the transition between these two worlds. “We expect that quantum properties will become weaker or even disappear entirely above a certain system size. In order to be able to study this transition and the associated quantum state, we have developed a novel concept consisting of a very large test system of 100 distinguishable photons that will form the basis of measurements and that will enable these measurements to be carried out without losing a single photon. The cable itself will be made of superconducting material and the experiments will be carried out at low temperatures,” explains Professor Wilhelm-Mauch. Up until now attempts to make these sorts of measurements have suffered from significant photon losses. Using the conventional methods available today a measurement on a system of 100 photons ends up measuring only one single photon. As the light quanta can simultaneously occupy several states, any measurement, once made, can provide only a very limited view of what is an extremely complex process. A single measured value can only ever describe one of the many possible states. “That’s why we’re making our test system with 100 photons as large as is practically feasible today, as this will allows us to study these highly entangled processes. The data from such measurements should give us a much more precise view of the processes involved,” says Wilhelm-Mauch.

To do this the researchers “trick” the laws of conventional wave optics. They combine quantum optics with so-called “left-handed media” to transmit the light quanta through a metamaterial. These lattices of nanoscale structures have been the subject of research in conventional optics for quite some time and they have a very special property: light impinging on such a left-handed material is refracted more strongly than is possible in a naturally occurring material, such as water. The angle of refraction can be altered by modifying the structure of the material. The Saarbrücken physicists have come up with a mathematical model of a lattice that is tailored to microwave photons and that for the first time is good enough for quantum optic studies. The metamaterial devised by Wilhelm-Mauch’s team is a so-called “left-handed artificial transmission line” that comprises a number of minute capacitors and inductors connected in series. The resulting waveguide allows a large number of photons to be packed into a tiny spatial volume, enabling them to be transmitted within a cable. The research team wants to use this system for quantum optic measurements.

The researchers are particularly interested in the transition from the world of classical physics to the quantum world. Knowing more about this interface will improve our understanding of macroscopic systems that make use of quantum effects. For instance, research of this kind could open up new possibilities in quantum computing. “If we can find out what is the maximum size of a system that still follows quantum mechanical laws, we would be able to make storage capacity as large as this limit allows,” explains Frank Wilhelm-Mauch. The theoretical physicist is a member of the international quantum computing research network “SCALEQIT”. As part of his work within the SCALEQIT project, Wilhelm-Mauch has already developed a highly efficient microwave detector that can detect photons with 100% efficiency. Currently scientists at the University of Karlsruhe in Germany and Syracuse University in the USA are working on a prototype of the micro lab.

![[Fe]-hydrogenase catalysis visualized using para-hydrogen-enhanced nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy](https://img.chemie.de/Portal/News/675fd46b9b54f_sBuG8s4sS.png?tr=w-712,h-534,cm-extract,x-0,y-16:n-xl)