Research shows potential for quasicrystals

Article outlines new optics research opportunities, including smaller optical circuits

Advertisement

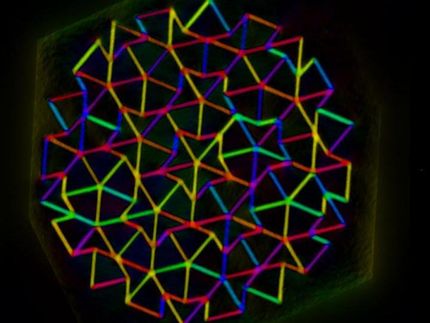

Ever since their discovery in 1984, the burgeoning area of research looking at quasiperiodic structures has revealed astonishing opportunities in a number of areas of fundamental and applied research, including applications in lasing and sensing. Quasiperiodic structures, or quasicrystals, because of their unique ordering of atoms and a lack of periodicity, possess remarkable crystallographic, physical and optical properties not present in regular crystals. In Nature Photonics, Amit Agrawal, professor in the Syracuse University College of Engineering and Computer Science along with his colleagues from the University of Utah present the history of quasicrystals and how this area can open up numerous opportunities in fundamental optics research including possibilities for building smaller optical circuits, performing lithography at a much smaller length scale and making more efficient optical devices that can be used for biosensing, solar cells or spectroscopy applications.

Up until their discovery, researchers including crystallographers, material scientists, physicists and engineers, only focused around two kinds of structures: periodic (e.g. a simple cubic lattice) and random (e.g. amorphous solids such as glass). Periodic structures are known for their predictable symmetry, both rotational and translational, and they were believed to be the only kinds of repeating structures that could occur in nature. From basic solid state physics, these structures are only allowed to exhibit strict 2, 3, 4 or 6-fold rotational symmetry, i.e., upon rotation by a certain angle about a crystallographic axis, the shape would still look identical upon each rotation. It was not believed that there could be a structure that existed which violated these four symmetry rules. Random systems, the other big area of research, looks at amorphous or disordered media like gases.

The introduction of quasicrystals - an ordered structure that lacks periodicity, exhibits some properties similar to periodic structures (such as atomic ordering over large-length scales) while violates rotational symmetry rules associated with them (i.e., a quasicrystal can exhibit 5 or 8 fold rotational symmetry) - was an area initially met with resistance from the research community. Agrawal explores this transition from skepticism to the ultimate acceptance by a growing number of researchers exploring the potential of these unique structures.

Most read news

Other news from the department science

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.