Iowa State, Ames Lab researchers find new properties of the carbon material graphene

Findings could have applications in high-speed communications fields

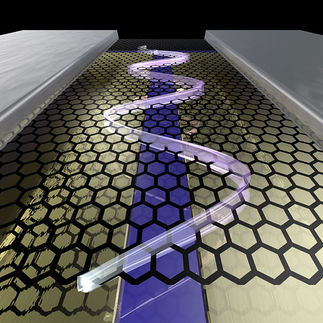

graphene has caused a lot of excitement among scientists since the extremely strong and thin carbon material was discovered in 2004. Just one atom thick, the honeycomb-shaped material has several remarkable properties combining mechanical toughness with superior electrical and thermal conductivity.

Now a group of scientists at Iowa State University, led by physicist Jigang Wang, has shown that graphene has two other properties that could have applications in high-speed telecommunications devices and laser technology – population inversion of electrons and broadband optical gain.

Wang is an assistant professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences at Iowa State University. He also is an associate scientist with the Department of Energy's Ames Laboratory.

Wang's team flashed extremely short laser pulses on graphene. The researchers immediately discovered a new photo-excited graphene state characterized by a broadband population inversion of electrons. Under normal conditions, most electrons would occupy low-energy states and just a few would populate higher-energy states. In population-inverted states, this situation is reversed: more electrons populate higher, rather than lower, energy states. Such population inversions are very rare in nature and can have highly unusual properties. In graphene, the new state produces an optical gain from the infrared to the visible.

Simply stated, optical gain means more visible light comes out than goes in. This can only happen when the gain medium is externally pumped and then stimulated with light (stimulated emission). Wang's discovery could open doors for efficient amplifiers in the telecommunication industry and extremely fast opto-electronics devices.

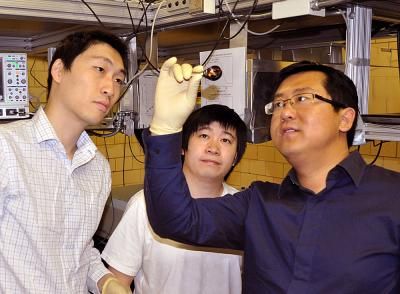

Iowa State physicist Jigang Wang, right, examines graphene monolayers grown on a substrate mounted in a cooper adapter as graduate students Tianq Li, far left, and Liang Luo look on in Wang's laboratory.

Steve Jones/College of Liberal Arts and Science, Iowa State University

Graphene as a gain medium for light amplification

"It's very exciting," Wang said. "It opens the possibility of using graphene as a gain medium for light amplification. It could be used in making broadband optical amplifiers or high-speed modulators for telecommunications. It even provides implications for development of graphene-based lasers."

Wang's team unveiled its findings in the journal Physical Review Letters on April 16. In addition to Wang, the paper's other authors are Tianq Li, Liang Luo and Junhua Zhang, Iowa State physics graduate students; Miron Hupalo, Ames Laboratory scientist; and Michael Tringides and Jörg Schmalian, Iowa State physics professors and Ames Laboratory scientists.

Wang is a member of the Condensed Matter Physics program at Iowa State and the Ames Laboratory. He and his team conduct optical experiments using laser spectroscopy techniques, from the visible to the mid-infrared and far-infrared spectrum. They use ultrashort laser pulses down to 10 quadrillionths of a second to study the world of nanoscience and correlated electron materials.

In 2004 United Kingdom researchers Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov discovered graphene, which led to their winning the 2010 Nobel Prize in Physics. Graphene is a two-dimensional (height and width) material with a growing list of known unique properties. It is a single layer of carbon only one atom thick. The carbon atoms are connected in a hexagonal lattice that looks like a honeycomb. Despite a lack of bulk, graphene is stronger than steel, it conducts electricity as well as copper and conducts heat even better. It is also flexible and nearly transparent.

An understanding gap existed, Wang explained, between the two scientific communities that studied the electronic and photonic properties of graphene. He believed his group could help bridge the gap by elaborating the non-linear optical properties of graphene and understanding the non-equilibrium electronic state. Wang explained that linear optical properties only transmit light – one light signal comes into a material and one comes out. "The non-linear property can change and modulate the signal, not just transmit it, producing functionality for novel device applications."

Graphene in a highly non-linear state

Wang said other scientists have studied graphene's optical properties, but primarily in the linear regime. His team hypothesized they could generate a new "very unconventional state" of graphene resulting in population inversion and optical gain.

"We were the first group to break new ground, to start looking at it in a highly excited state consisting of extremely dense electrons – a highly non-linear state. In such a state, graphene has unique properties."

Wang's group started with high-quality graphene monolayers grown by Hupalo and Tringides in the Ames Laboratory. The researchers used an ultrafast laser to "excite" the material's electrons with short pulses of light just 35 femtoseconds long (35 quadrillionths of a second). Through measurements of the photo-induced electronic states, Wang's team found that optical conductivity (or absorption) of the graphene layers changed from positive to negative – resulting in the optical gain – when the pump pulse energy was increased above a threshold.

The results indicated that the population inverted state in photoexcited graphene emitted more light than it absorbed. "The absorption was negative. It meant that population inversion is indeed established in the excited graphene and more light came out of the inverted medium than what entered, which is optical gain," Wang said. "The light emitted shows gain of about one percent for a layer a mere one atom thick, a figure on the same order to what's seen in conventional semiconductor optical amplifiers hundreds of times thicker."

The key to the experiments, of course, was creating the highly non-linear state, something "that does not normally exist in thermal equilibrium," Wang said. "You cannot simply put graphene under the light and study it. You have to really excite the electrons with the ultrafast laser pulse and have the knowledge on the threshold behaviors to arrive at such a state."

Wang said a great deal more engineering and materials perfection lies ahead before graphene's full potential for lasers and optical telecommunications is ever realized. "The research clearly shows, though, that lighting up graphenes may produce brighter emissions as well as a bright future," he said.