Watching electron motion in solids

Simplification of a spectroscopic method for investigating the movement of electrons in molecules and solids achieved

A spectroscopic method for analysing the extremely fast movements of electrons in solids can now be used much more easily than before thanks to a new approach. Researchers from the University of Oldenburg present the new method in the journal Optica. The team hopes that this will transform multidimensional electronic spectroscopy from a method for experts to a tool that can be widely used.

The ultrafast dynamics and interactions of electrons in molecules and solids have long remained hidden from direct observation. For some time now, it has been possible to study these quantum-physical processes – for example, during chemical reactions, the conversion of sunlight into electricity in solar cells and elementary processes in quantum computers – in real time with a temporal resolution of a few femtoseconds (quadrillionths of a second) using two-dimensional electronic spectroscopy (2DES). However, this technique is highly complex. Consequently, it has only been employed by a handful of research groups worldwide to date. Now a German-Italian team led by Prof. Dr. Christoph Lienau from the University of Oldenburg has discovered a way to significantly simplify the experimental implementation of this procedure. "We hope that 2DES will go from being a methodology for experts to a tool that can be widely used," explains Lienau.

Two doctoral students from Lienau's Ultrafast Nano-Optics research group, Daniel Timmer and Daniel Lünemann, played a key role in the discovery of the new method. The team has now published a paper in the journal Optica describing the procedure.

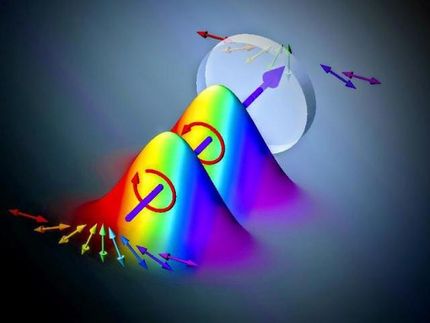

In 2DES, a sequence of three ultrashort laser pulses is used to excite the material to be investigated. The first two pulses must be identical copies and serve to trigger the process to be investigated in the material – for instance, to excite the electrons in a semiconductor or a dye, causing them to transition to a higher energy state. This changes the optical properties of the material. The third laser pulse, known as the "probe pulse", interacts with the excited system, transforms in the process and thus provides information about the state of the system.

By varying the time intervals between the three pulses, different sets of information about the system under investigation can be obtained. When the interval between the two excitation pulses and the probe pulse is altered, the process can be recorded at different stages so that the time sequence becomes visible – as if one were watching a film. The interval between the two excitation pulses can also be varied. This allows to selectively excite certain optical transitions in the material, the key for studying particularly complex processes such as energy transfer during photosynthesis. "The experimental implementation of the 2DES technique is very challenging," Lienau emphasises. The main problem is precise control of the time interval between the first two identical laser pulses, as well as of their shape, he explains.

In their new study, Lienau and his team describe a potential solution to the problem. The approach devised by the Oldenburg doctoral students Daniel Timmer and Daniel Lünemann is based on a method called TWINS that was introduced a few years ago by the Italian physicist Professor Giulio Cerullo from the Politecnico di Milan. Cerullo, who also co-authored the current study, developed a device called an interferometer that uses birefringent crystals to create two identical replicas of an input pulse. These are then used for excitation of the material under study. Although this method is considerably easier to implement than other solutions for generating pulses, it has certain limitations.

"This procedure has so far failed to attain the full functionality of a multidimensional electronic spectrometer," says Lienau. Experts in the field assumed that the technique developed by Cerullo would not be able to achieve that level of functionality, he adds.

However, Timmer and Lünemann came up with the idea of adding an optical component to Cerullo's interferometer, a so-called delay quarter wave plate which delays any light signal that passes through it by a predetermined fraction of a wavelength. Thanks to this relatively simple extension to the procedure the two researchers were able to control the two laser pulses far more precisely than with the original TWINS interferometer.

The researchers implemented their idea in experiments and demonstrated the enhanced possibilities of this method by using it to investigate the charge dynamics in an organic dye. The team also provided a theoretical explanation for the new method. Timmer, Lünemann and Lienau have now been granted a patent for the extended interferometry procedure.

Original publication

Other news from the department science

Most read news

More news from our other portals

See the theme worlds for related content

Topic World Spectroscopy

Investigation with spectroscopy gives us unique insights into the composition and structure of materials. From UV-Vis spectroscopy to infrared and Raman spectroscopy to fluorescence and atomic absorption spectroscopy, spectroscopy offers us a wide range of analytical techniques to precisely characterize substances. Immerse yourself in the fascinating world of spectroscopy!

Topic World Spectroscopy

Investigation with spectroscopy gives us unique insights into the composition and structure of materials. From UV-Vis spectroscopy to infrared and Raman spectroscopy to fluorescence and atomic absorption spectroscopy, spectroscopy offers us a wide range of analytical techniques to precisely characterize substances. Immerse yourself in the fascinating world of spectroscopy!