Squid tissues and chemistry combine for versatile hydrogels

The natural abilities of squid tissues and the creativity of chemists combine to take hydrogel research in new directions

Researchers at Hokkaido University in Japan have combined natural squid tissues with synthetic polymers to develop a strong and versatile hydrogel that mimics many of the unique properties of biological tissues. hydrogels are polymer networks containing large quantities of water, and are being explored for many uses, including medical prosthetics, soft robotic components and novel sensor systems.

Symbolic image

Computer-generated image

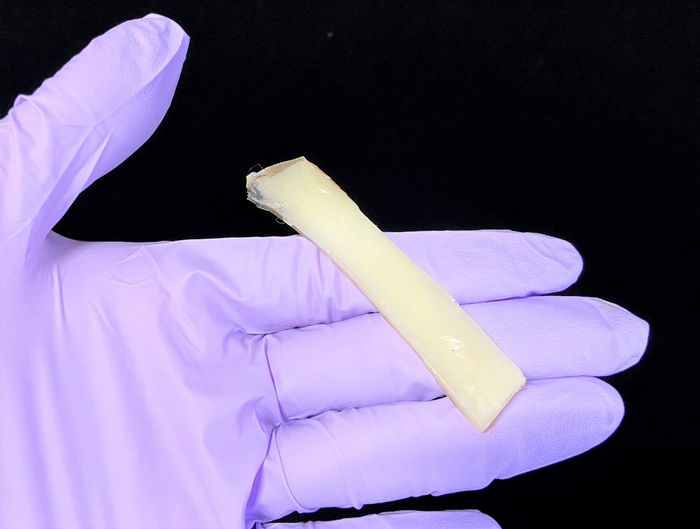

The new squid/synthetic polymer double-network gel developed in this study.

Tasuku Nakajima

The Hokkaido team report their contribution to this fast-moving research area in the journal NPG Asia Materials.

Natural biological tissues exhibit unique properties essential for their functions, which researchers are seeking to replicate in hydrogels. Muscles, for example, in addition to strength and flexibility, have physical properties that vary in different directions and are built from a hierarchy of structures working together. Bones and blood vessels also display these features, known as hierarchical anisotropy.

Unlike the natural tissues that researchers wish to mimic, most synthetic hydrogels have uniform properties in all directions and are structurally weak.

“By combining the properties of tissues derived from squid with synthetic polymers, we have demonstrated a hybrid strategy that serves as a general method for preparing hydrogels with useful hierarchical anisotropy and also toughness,” says polymer scientist Tasuku Nakajima of the Hokkaido University team.

The manufacturing process begins with commercially available frozen squid mantle – the main outer part of a squid. In live squid, the mantle expands to take water into the body, and then strongly contracts to shoot water outwards as a jet. This ability depends on the anisotropic muscles within squid connective tissue. The researchers took advantage of the molecular arrangements within this natural system to build their bio-mimicking gel.

Chemical and heat treatment of thin slices of the defrosted squid tissue mixed with polyacrylamide polymer molecules initiated formation of the cross-linked hybrid hydrogel. It has what is known as a double-network structure, with the synthetic polymer network embedded and linked within the more natural muscle fiber network derived from squid mantle.

“The DN gel we synthesized is much stronger and more elastic than the natural squid mantle,” explains Professor Jian Ping Gong, who led the team. “The unique composite structure also makes the material impressively resistant to fracture, four times tougher than the original material.”

The current proof-of-concept work should be just the start for exploring many other hybrid hydrogels that could exploit the unique properties of other natural systems. Jellyfish have already been used as a source of material for simpler single-network hydrogels, so are an obvious next choice for exploring hybrid double-network options.

“Possible applications include load-bearing artificial fibrous tissues, such as artificial ligaments and tendons, for medical use,” says Gong. Further work by the team will explore the biocompatibility of the gels and investigate options for making a range of gels suitable for different uses.