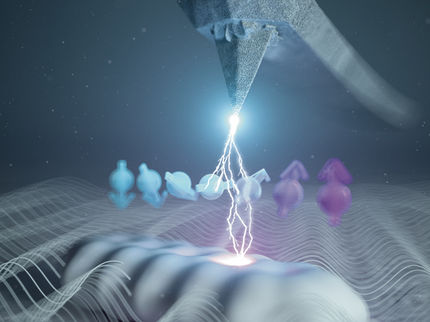

A radical new approach in synthetic chemistry

Pulse radiolysis experiments help reveal how unpaired electrons at one end of a molecule can initiate chemistry at 'distant' locations

Advertisement

Scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory helped measure how unpaired electrons in atoms at one end of a molecule can drive chemical reactivity on the molecule’s opposite side. As described in a paper recently published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, this work, in collaboration with Princeton University, shows how molecules containing these so-called free radicals could be used in a whole new class of reactions.

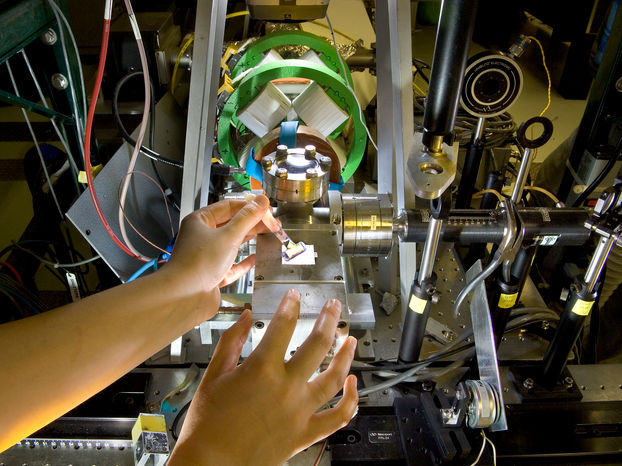

The Laser Electron Accelerator Facility (LEAF) generates intense high-energy electron pulses that allow scientists to add or subtract electrons from molecules to make chemically reactive species and monitor what happens as a reaction proceeds.

Brookhaven National Laboratory

“Most reactions involving free radicals take place at the site of the unpaired electron,” explained Brookhaven Lab chemist Matthew Bird, one of the co-corresponding authors on the paper. The Princeton team had become experts in using free radicals for a range of synthetic applications, such as polymer upcycling. But they’ve wondered whether free radicals might influence reactivity on other parts of the molecule as well, by pulling electrons away from those more distant locations.

“Our measurements show that these radicals can exert powerful ‘electron-withdrawing’ effects that make other parts of the molecule more reactive,” Bird said.

The Princeton team demonstrated how that long-distance pull can overcome energy barriers and bring together otherwise unreactive molecules, potentially leading to a new approach to organic molecule synthesis.

Combining capabilities

The research relied on the combined resources of a Princeton-led DOE Energy Frontier Research Center (EFRC) focused on Bio-Inspired Light Escalated Chemistry (BioLEC). The collaboration brings together leading synthetic chemists with groups having advanced spectroscopic techniques for studying reactions. Its funding was recently renewed for another four years.

Robert Knowles, who led Princeton’s role in this research, said, “This project is an example of how BioLEC’s combined expertise enabled the team to quantify an important physical property of these radical species, that in turn allowed us to design the resulting synthetic methodology.”

The Brookhaven team’s major contribution is a technique called pulse radiolysis—available only at Brookhaven and one other location in the U.S.

“We use the Laser Electron Accelerator Facility (LEAF)—part of the Accelerator Center for Energy Research (ACER) in Brookhaven’s Chemistry Division—to generate intense high-energy electron pulses,” Bird explained. “These pulses allow us to add or subtract electrons from molecules to make reactive species that might be difficult to make using other techniques, including short-lived reaction intermediates. With this technique, we can step into one part of a reaction and monitor what happens.”

For the current study, the team used pulse radiolysis to generate molecules with oxygen-centered radicals, and then measured the “electron-withdrawing” effects on the other side of the molecule. They measured the electron pull by tracking how much the oxygen at the opposite side attracts protons, positively charged ions sloshing around in solution. The stronger the pull from the radical, the more acidic the solution has to be for protons to bind to the molecule, Bird explained.

The Brookhaven scientists found the acidity had to be high to enable proton capture, meaning the oxygen radical was a very strong electron withdrawing group. That was good news for the Princeton team. They then demonstrated that it’s possible to exploit the “electron-withdrawing” effect of oxygen radicals by making parts of molecules that are generally inert more chemically reactive.

“The oxygen radical induces a transient ‘polarity reversal’ within the molecule—causing electrons that normally want to remain on that distant side to move toward the radical to make the ‘far’ side more reactive,” Bird explained.

These findings enabled a novel substitution reaction on phenol based starting materials to make more complex phenol products.

“This is a great example of how our technique of pulse radiolysis can be applied to cutting-edge science problems,” said Bird. “We were delighted to host an excellent graduate student, Nick Shin, from the Knowles group for this collaboration. We look forward to more collaborative projects in this second phase of BioLEC and seeing what new problems we can explore using pulse radiolysis.”