How to cool more efficiently

Scientists break new ground in future refrigeration

In the journal Applied Physics Reviews, an international research team from the University of Barcelona, the Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf (HZDR), and TU Darmstadt report on possibilities for implementing more efficient and environmentally friendly refrigeration processes. For this purpose, they investigated the effects of simultaneously exposing certain alloys to magnetic fields and mechanical stress.

Symbolic image

Alexas_Fotos, pixabay.com

In the past, researchers were mainly concerned with the well-known “magnetocaloric effect”, which can be observed when certain metals and alloys are exposed to a magnetic field: The materials spontaneously change their magnetic order as well as their temperature, which makes them promising candidates for magnetic cooling circuits. “It has recently been found that we can boost this effect considerably in certain materials by simultaneously adding other stimuli, such as a force field, or more specifically, a mechanical load,” says Dr. Tino Gottschall from the High Magnetic Field Laboratory (HLD) at HZDR, describing the team’s approach. A small range of such “multicaloric” materials is already known.

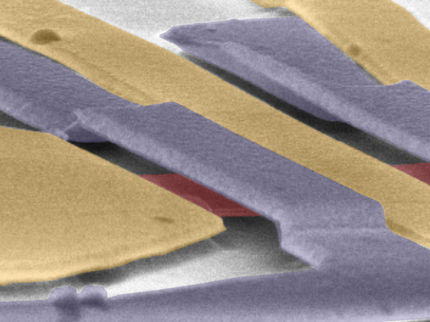

The research team selected a special nickel-manganese-indium alloy as one of the most promising materials for their experiments. It is one of the magnetic “shape memory” alloys, whose memory is a result of the transformation of two different crystal lattices: If there is an external stimulus, such as a magnetic field, these structures morph into each other, resulting in noticeable alterations in the material – for instance, clearly perceptible shape changes are not uncommon. The special feature of the selected compound is, however, that at a certain temperature at which the crystal structures change, the magnetic properties of the compound also change abruptly: structure and magnetism are strongly coupled.

A custom-made measuring device

In order to determine the material properties that are necessary for an efficient cooling process, the team in Barcelona first had to develop a unique, specially designed calorimeter to measure heat and that enables the simultaneous application of a magnetic field and pressure to the sample. To do this, the scientists harnessed a familiar method from materials testing and adapted it for their purposes, subjecting the sample to uniaxial mechanical stress.

While the magnetic flux densities ranged up to 6 Tesla, which is 120,000 times stronger than the Earth’s magnetic field, the peak compressive stress applied was a moderate 50 megapascals. For the given sample size, that force roughly corresponds to a mass of 20 kilograms. “One can apply this kind of pressure by hand. And that is the decisive aspect for future applications, because such manageable mechanical loads are relatively easy to implement,” explains Prof. Lluís Mañosa from the University of Barcelona, adding: “The challenge for us was to integrate accurate measurements of both compressive stress and strain into our calorimeter without distorting the measurement conditions.”

Wanted: process control for practical application

Evaluating the obtained results was quite complex. The researchers recorded various parameters simultaneously, such as temperature change, magnetic flux density, compressive stress, and the alloy’s entropy during programmed cooling and heating phases near a specific temperature at which the given material experiences transformations in the crystal lattice that lead to a change in magnetization. In the alloy used, this process occurs at room temperature, which is also advantageous for later practical application.

The measurements chart the sample’s behavior in a four-dimensional space. Mapping this space in a meaningful way requires a raft of experiments, resulting in large-scale measurement campaigns. For Prof. Oliver Gutfleisch of TU Darmstadt, the effort is worthwhile: “The interaction of the different stimuli in multicaloric materials has hardly been investigated so far. Our nickel-manganese-indium alloy is the best-researched prototype compound in this class of materials to date. Our work has filled in some blank spots on its property map.”

Now the scientists can pragmatically assess the benefit of additional pressure load – a central research objective of the ERC Advanced Grant Project Cool Innov. In a cooling cycle with commercially available neodymium permanent magnets, the cooling efficiency could be doubled by simultaneously applying a force field. The team assumes that the new process will also be of great value when searching for other promising cooling materials for the future.