Tellurium makes the difference

International research team discovers unusual molecular structures

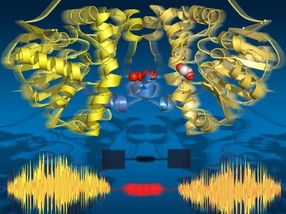

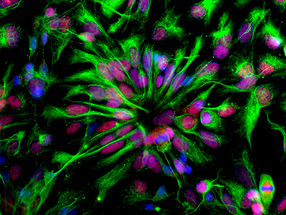

The periodic system contains 118 chemical elements. However, only a few of them, such as hydrogen, carbon, nitrogen, oxygen and silicon, are of major importance in our daily lives. But things become really exciting from a chemical point of view when less well-known elements are involved. An international research group from Germany and Finland discovered astonishing and beautiful molecular structures when, instead of oxygen or sulphur, they used the element tellurium, which has a different weight, in ring-shaped hydrocarbon molecules. These compounds are distinguished by the fact that they are arranged in the crystal to form highly symmetrical tubes that interact with each other via the tellurium atoms.

Professor Dr Wolfgang Weigand presents unusual structures of telluric compounds

Anne Günther (University of Jena)

Molecular rings are arranged into tubes

The semiconductor tellurium has similar chemical properties to the ‘related’ elements sulphur and selenium. It is therefore not surprising that the ring-shaped hydrocarbons, into which the team specifically incorporated tellurium atoms, also behave similarly to the corresponding known compounds that contain sulphur or selenium – at least when they are dissolved. Tellurium nevertheless occupies a special position.

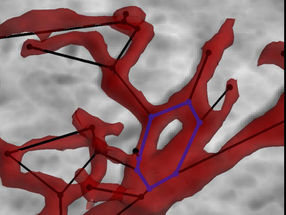

“Something special happens when these substances form crystals,” says Prof. Wolfgang Weigand of Friedrich Schiller University Jena, one of the two corresponding authors of the current publication on this topic. “Virtually infinitely long tubes are then formed, in which the ring-shaped molecules are held together by the tellurium atoms. This happens due to an unusually strong intermolecular interaction. As a result, very interesting structures are created, which we can observe here.” Similar structures are already known in chemistry, for example those called metal-organic frameworks. “In contrast to those, however, our compounds are not coordination polymers,” explains Weigand. “Therefore, they behave differently. This can be seen, for example, in the fact that they only make these supramolecular forms as crystals and not when they are dissolved.” However, initial experimental findings show that atmospheric oxygen can oxidise the tellurium atoms and then link them together to form stacked compounds.

A new way to store gas?

The German-Finnish research team has discovered that, due to their special cavities, these tellurium compounds in solid form have an extremely large surface area of nearly 1000 square metres per gram – or around two-and-a-half basketball courts. “It is in principle conceivable that gases, such as carbon dioxide, could be captured in these cavities,” says Wolfgang Weigand. “However, it was important to us first of all to explore and study these exciting compounds.” Further research is needed before practical applications could become possible.

“This research would not have been possible without the EU’s Erasmus Programme,” adds Jena chemist Weigand. “The idea for this work originally came from my former doctoral candidate, Dr Tobias Niksch, in Jena, and through a stay as a visiting scientist at the University of Oulu in Finland by my former Master’s student, Marko Rodewald, in the group led by Prof. Risto Laitinen. We have had a very good relationship with the university for 15 years and we have frequently published research results together. And the theoretical calculations in this paper were done by one of Risto Laitinen’s former doctoral candidates, who is now doing research at the University of Jyväskylä in Finland. This paper therefore shows how important exchanges and networking are for scientific progress. I’m already looking forward to doing further research on these interesting structures with our Finnish colleagues.”