New laser makes silicon 'sing'

Yale scientists have created a new type of silicon laser that uses sounds waves to amplify light. In recent years, there has been increasing interest in translating optical technologies -- such as fiber optics and free-space lasers -- into tiny optical or "photonic" integrated circuits. Using light rather than electricity for integrated circuits permits sending and processing information at speeds that would be impossible with conventional electronics. Researchers say silicon photonics -- optical circuits based on silicon chips -- are one of the leading platforms for such technologies, thanks to their compatibility with existing microelectronics.

"We've seen an explosion of growth in silicon photonic technologies the past few of years," said Peter Rakich, an associate professor of applied physics at Yale who led the research. "Not only are we beginning to see these technologies enter commercial products that help our data centers run flawlessly, we also are discovering new photonic devices and technologies that could be transformative for everything from biosensing to quantum information on a chip. It's really an exciting time for the field."

The researchers said this rapid growth has created a pressing need for new silicon lasers to power the new circuits -- a problem that has been historically difficult due to silicon's indirect bandgap. "Silicon's intrinsic properties, although very useful for many chip-scale optical technologies, make it extremely difficult to generate laser light using electrical current," said Nils Otterstrom, a graduate student in the Rakich lab and the study's first author. "It's a problem that's stymied scientists for more than a decade. To circumvent this issue, we need to find other methods to amplify light on a chip. In our case, we use a combination of light and sound waves."

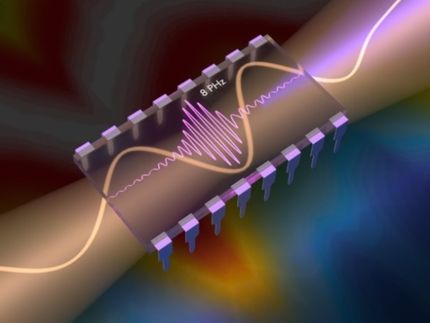

The laser design corrals amplified light within a racetrack shape -- trapping it in circular motion. "The racetrack design was a key part of the innovation. In this way, we can maximize the amplification of the light and provide the feedback necessary for lasing to occur," Otterstrom said.

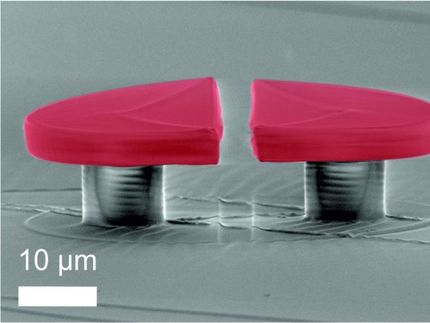

To amplify the light with sound, the silicon laser uses a special structure developed in the Rakich lab. "It's essentially a nanoscale waveguide that's is designed to tightly confine both light and sound waves and maximize their interaction," Rakich said.

"What's unique about this waveguide is that there are two distinct channels for light to propagate," added Eric Kittlaus, a co-author of the study and a graduate student in the Rakich lab. "This allows us to shape the light-sound coupling in a way that permits remarkably robust and flexible laser designs."

Without this type of structure, the researchers explained, amplification of light using sound would not be possible in silicon. "We've taken light-sound interactions that were virtually absent in these optical circuits, and have transformed them into the strongest amplification mechanism in silicon," Rakich said. "Now, we're able to use it for new types of laser technologies no one thought possible 10 years ago."

Otterstrom said there were two main challenges in developing the new laser: "First, designing and fabricating a device where the amplification outpaces the loss, and then figuring out the counter-intuitive dynamics of this system," he said. "What we observe is that while the system is clearly an optical laser, it also generates very coherent hypersonic waves."

The research team said these properties may lead to a number of potential applications ranging from integrated oscillators to new schemes for encoding and decoding information. "Using silicon, we can create a multitude of laser designs, each with unique dynamics and potential applications," said co-author Ryan Behunin, an assistant professor at Northern Arizona University and a former member of the Rakich lab. "These new capabilities dramatically expand our ability to control and shape light in silicon photonic circuits."

Original publication

Other news from the department science

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.