Rutgers physicists discover novel electronic properties in two-dimensional carbon structure

Previously predicted but unobserved interactions between massless particles may lead to speedy, powerful electronic devices

Rutgers researchers have discovered novel electronic properties in two-dimensional sheets of carbon atoms called graphene that could one day be the heart of speedy and powerful electronic devices.

The new findings, previously considered possible by physicists but only now being seen in the laboratory, show that electrons in graphene can interact strongly with each other. The behavior is similar to superconductivity observed in some metals and complex materials, marked by the flow of electric current with no resistance and other unusual but potentially useful properties. In graphene, this behavior results in a new liquid-like phase of matter consisting of fractionally charged quasi-particles, in which charge is transported with no dissipation.

In a paper issued online by the science journal Nature and slated for print publication in the coming weeks, physics professor Eva Andrei and her Rutgers colleagues note that the strong interaction between electrons, also called correlated behavior, had not been observed in graphene in spite of many attempts to coax it out. This led some scientists to question whether correlated behavior could even be possible in graphene, where the electrons are massless (ultra-relativistic) particles like photons and neutrinos. In most materials, electrons are particles that have mass.

"Our work demonstrated that earlier failures to observe correlated behavior were not due to the physical nature of graphene," said Eva Andrei, physics professor in the Rutgers School of Arts and Sciences. "Rather, it was because of interference from the material which supported graphene samples and the type of electrical probes used to study it."

This finding should encourage scientists to further pursue graphene and related materials for future electronic applications, including replacements for today's silicon-based semiconductor materials. Industry experts expect silicon technology to reach fundamental performance limits in a little more than a decade.

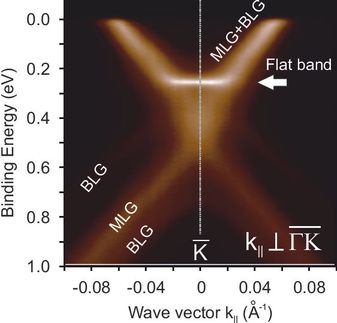

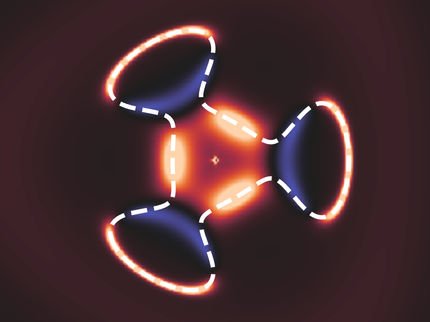

The Rutgers physicists further describe how they observed the collective behavior of the ultra-relativistic charge carriers in graphene through a phenomenon known as the fractional quantum Hall effect (FQHE). The FQHE is seen when charge carriers are confined to moving in a two-dimensional plane and are subject to a perpendicular magnetic field. When interactions between these charge carriers are sufficiently strong they form new quasi-particles with a fraction of an electron's elementary charge. The FHQE is the quintessential signature of strongly correlated behavior among charge-carrying particles in two dimensions.

The FHQE is known to exist in semiconductor-based, two-dimensional electron systems, where the electrons are massive particles that obey conventional dynamics versus the relativistic dynamics of massless particles. However, it was not obvious until now that ultra-relativistic electrons in graphene would be capable of exhibiting collective phenomena that give rise to the FHQE. The Rutgers physicists were surprised that the FHQE in graphene is even more robust than in standard semiconductors.

Scientists make graphene patches by rubbing graphite – the same material in ordinary pencil lead – onto a silicon wafer, which is a thin slice of silicon crystal used to make computer chips. Then they run electrical pathways to the graphene patches using ordinary integrated circuit fabrication techniques. While scientists were able to investigate many properties of the resulting graphene electronic device, they were not able to induce the sought-after fractional quantum Hall effect.

Andrei and her group proposed that impurities or irregularities in the thin layer of silicon dioxide underlying the graphene were preventing the scientists from achieving the exacting conditions they needed. Postdoctoral fellow Xu Du and undergraduate student Anthony Barker were able to show that etching out several layers of silicon dioxide below the graphene patches essentially leaves an intact graphene strip suspended in mid-air by the electrodes. This enabled the group to demonstrate that the carriers in suspended graphene essentially propagate ballistically without scattering from impurities. Another crucial step was to design and fabricate a probe geometry that did not interfere with measurements as Andrei suspected earlier ones were doing. These proved decisive steps to observing the correlated behavior in graphene.

In the past few months, other academic and corporate research groups have reported streamlined graphene production techniques, which will propel further research and potential applications.

Most read news

Other news from the department science

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.