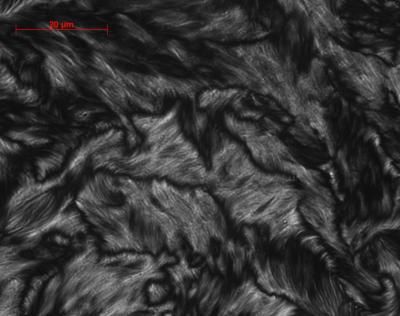

A crystal clear view of chalk formation

It has a beautiful, but also an unpleasant side: crystallization determines the shape of precious stones, but also causes the lime scale in washing machines. How this comes about, has been known for a long time - or has it? Scientists at the Max Planck Institute of colloids and Interfaces are now whittling away at the established theory, which is unable to explain numerous phenomena. The researchers investigated the crystallization of calcium carbonate, known commonly as chalk, and found that stable nanoclusters form in water with a small quantity of dissolved calcium carbonate - not how it was assumed to happen in the past. The lime scale deposits that will eventually bring a washing machine to a standstill are created from these tiny chalk particles. Previously, it was also an unknown fact that the structure of crystallized calcium carbonate depends on the alkalinity of the solution. These new findings might provide help in coping with the lime scale in washing machines, as well as help to explain the sophisticated structure of biominerals - and to better understand the role of the oceans as carbon dioxide sinks.

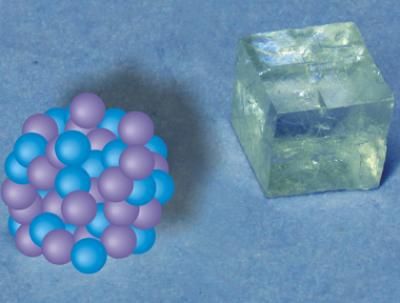

Around 70 calcium and carbonate ions come together to form a stable nanocluster, shown here schematically and not to scale. The structure of the crystal (right) is most likely already determined in this cluster.

Denis Gebauer / Max Planck Institute of Colloids and Interfaces

Calcium carbonate is ubiquitous: everyone has probably held a stick of blackboard chalk in the hand at one time or another, or railed against the deposits it forms in washing machines. It is the main constituent of marble, dolomite and many types of sediment, and it is also found in the shells of crabs, mussels, snails, sea urchins and in single-celled organisms. These biomaterials have properties that make them interesting for applications in medicine and building materials technology. The ingenious structure of their crystals at nanoscopic level makes them particularly robust. Materials scientists would like to know how organisms produce these structures, so that they can copy them.

Researchers at the Max Planck Institute in Golm near Potsdam have now made a contribution to achieving this aim by demonstrating that calcium carbonate crystals are created differently from the way they were previously thought to form. When calcium and carbonate ions come together in a solution, they form stable nanoclusters consisting of around 70 calcium and carbonate ions - and they do that even in very soft water, a dilute solution from which chalk does not normally precipitate. If the concentration of dissolved calcium carbonate is increased, the clusters clump together and the mineral crystallizes.

"It seems that it is already decided when the clusters form, which of the three anhydrous crystal structures calcium carbonate will assume," says Helmut Cölfen who headed the study. "We also observed that the crystal structure depends on the pH level." Under low alkaline conditions, calcium carbonate forms calcite, its most stable crystalline structure. In a more alkaline environment, it creates vaterite, a non-stable crystalline structure.

"Our results suggest that the pH level influences the way the ions group together in these clusters, which are just two nanometers in size," explains Denis Gebauer, who played a crucial part in the study. At this stage, they do not form a regular crystal structure, but it is highly likely that the rudimentary arrangement of the crystal is already recognizable. If the clusters then group together into increasingly larger aggregates, this arrangement can remain in place. A transient amorphous form, that is, a non-crystalline solid, is initially created, which then changes into a crystal.

If crystallization really did take this route, it would be easier to understand how mussels, for example, construct their shells or a sea urchin forms its spines. As the tiny clusters with which crystallization starts are stable, organisms would have to intervene only at this early stage to influence the structure. They might use the pH level or biomolecules to do this.

The theory of crystallization that has prevailed so far leaves little room for influencing the arrangement of the ions in the regular crystal lattice early on. It assumes that the ions do not group together until a certain concentration has been exceeded. If these clusters do not reach a minimum size, they break apart. It is only when they can get beyond the size of the "critical crystal nucleus" that it becomes possible for the nucleus to grow into a crystal. The earliest point at which the crystal structure could be influenced would therefore be the critical nucleus.

The researchers in Golm used calcium phosphate and calcium oxalate to test whether other minerals also follow this crystallization pathway. Calcium phosphate is the main constituent of bones and teeth; kidney stones are predominately made up of calcium oxalate. The scientists subjected these materials to the same test as calcium carbonate. Drop by drop they added a solution containing calcium ions to a solution with the other component - that is, carbonate, phosphate or oxalate ions. With a special electrode they measured how many of the added calcium ions were present in the solution. It turned out that also in the experiments with calcium phosphate and calcium oxalate, there were fewer ions available than the researchers had added - they must therefore have been fixed into clusters, as was the case with the calcium carbonate.

The newly proposed mechanism of crystallization also has consequences for technology. "The stable clusters offer a new point at which to tackle lime scale deposits - not only in washing machines and dish washers, but also in industry," says Helmut Cölfen. This problem causes around 50 billion dollars worth of damage each year in industrial nations. Initially, traditional scale inhibitors fish out the calcium ions from the water, and secondly they bind the tiny precipitated crystals and stop them growing. "Now it will be possible to develop new types of scale inhibitors that prevent the nanoclusters from joining up to form larger structures," says Cölfen. "This is more effective than the traditional approaches."

These discoveries about crystallization also have consequences for climate change. The clusters bind carbon dioxide as carbonate. Up to now it has only been known that calcium carbonate mineral stores this greenhouse gas. As the nanoscopic clusters also form in the oceans, they prevent more carbon dioxide from entering the atmosphere than previously assumed for calcium carbonate minerals. However, there is a problem: the oceans are acidifying because a considerable proportion of the carbon dioxide from the atmosphere is dissolving into them as carbonic acid. "When the pH level falls, less carbonate can be bound in the clusters," says Helmut Cölfen. This allows more carbon dioxide to be released into the atmosphere, where it turns the global heating system up another notch.

Original work: Denis Gebauer, Antje Völkel, Helmut Cölfen; "Stable Prenucleation Calcium Carbonate Clusters Science"; Science 2008 .