Physicists describe strange new fluid-like state of matter

Comparison of granular jets at atmospheric pressure and in a vacuum

Advertisement

University of Chicago physicists have created a novel state of matter using nothing more than a container of loosely packed sand and a falling marble. They have found that the impacting marble produces a jet of sand grains that briefly behaves like a special type of dense fluid.

"We're discovering a new type of fluid state that seems to exist in this combination of gas-air in this case-and a dense arrangement of particles," said Heinrich Jaeger, Professor in Physics and Director of the Materials Research Science and Engineering Center at the University of Chicago. Jaeger's team describes the surprising phenomenon in Nature Physics.

Scientists typically have produced new states of matter at ultra-cold temperatures, those nearing absolute zero. In this case, granular materials take on unusual characteristics at room temperature. "The jet acts like an ultra-cold, ultra-dense gas, not in terms of ambient temperature, but in terms of how we define temperature via the random motion of particles. Inside the jet there is very, very little random motion," Jaeger said.

The jetting phenomenon was first reported in 2001 by Sigurdur Thoroddsen and Amy Shen, who were then at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Studying the way the characteristics of granular materials changes from solid to fluid has long been a research theme at Chicago's Center for Materials Research. Thoroddsen and Shen's work led Jaeger to suggest that Floir reproduce the experiment as the subject of his undergraduate honors thesis. Meanwhile, a group led by Detlef Lohse at the University of Twente in the Netherlands used high-speed video and computer simulations to infer how the jet was caused by gravity as material rushed in to fill the void left behind by the impacting object.

But to actually demonstrate the underlying cause of the jet's formation, the Chicago team needed very fast, non-invasive tracking of the interior of the sand. To this end, the Chicago scientists used high-speed X-ray radiography. Taken at 5,000 frames per second, the X-ray images were the fastest ever taken at Argonne National Laboratory's Advanced Photon Source, which produces the most brilliant X-ray beams for research in the Western Hemisphere.

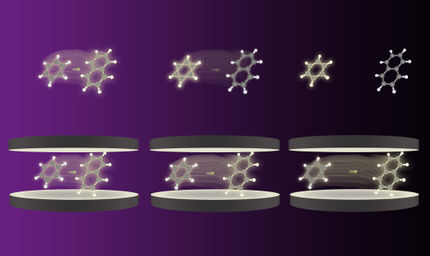

The experiments, conducted at both atmospheric pressure and in a vacuum, showed that air compressed between the sand grains provides most of the energy that drives the jet. The University of Twente's Lohse said he regards the work of Jaeger's team as "very important."

Systematically reducing the pressure, Jaeger's team observed that the jet, in fact, consisted of two stages. Air pressure exerted little influence on the jet's initial stage, a thin stream of particles that breaks up into droplets. But air pressure played a key role in forming the jet's second stage, characterized by a thick column of particles with ripples on its surface.

"One of the biggest questions that we have still not solved is why this jet is so sharply delineated. Why are there these beautiful boundaries? Why isn't this whole thing just falling apart," Jaeger asked.

Jaeger's team needed advanced scientific equipment and support from the National Science Foundation and the U.S. Department of Energy to conduct this study. To observe the basic effect, however, "You can do this experiment at home," he said. Take a cup of powdered sugar and pour it into another container to ensure that it is loosely packed. Then, drop a marble into the cup. "Once you drop that marble in there, you see that jet emerging, but you have to look fast."