Soft shell, hard core: nanotubes made of cyclic peptides with a synthetic polymer coating

Ever since the discovery of carbon nanotubes in the early 1990s, scientists and engineers have been fascinated by the possibilities for these little tubes made of organic materials in the fields of microelectronics, substance separation, and biomedicine. Freiburg researchers have now produced novel nanotube hybrids from peptides and polymers: nanotubes made of cyclic peptides are coated with a soft polymeric plastic shell.

Cyclic peptides are small molecules whose amino acid chains form a ring. The amino and acid groups, as well as the hydrogen atom can be arranged in two ways around the first carbon atom (known as the 'alpha C-atom') of an amino acid. This allows the molecule to have either a 'left' or a 'right' configuration. While mother nature uses almost exclusively 'left' amino acids in proteins, the team headed by Markus Bieslaski at IMTEK (Institute of Microsystem Technology) are building up cyclic peptides according to the 'one right, one left' scheme, a technique that has been pioneered by Reza Ghadiri (Scripps Institute, San Diego). Such peptide rings organize themselves into a tiny tubular structure. All of the peptide side chains stick out of the tube, leaving a cavity inside. The dimensions of the tube are determined by the number of amino acid building blocks in the peptide rings.

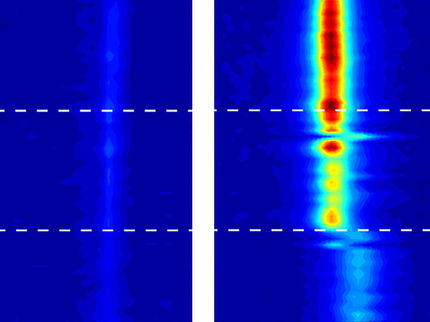

The special trick in this case is that some of the side chains selected are of a type that can act as starting points for the growth of artificial polymer chains. They can thus form a strongly bound shell of soft plastic around the relatively hard peptide nanotube. In their initial experiments, the researchers used N-isopropylacrylamide as the molecular building block for the polymer. Images obtained with an atomic force microscope revealed solvent-free ('dry') individual rod-shaped objects about 80 nm long and 12 nm high.

The plastic used is not toxic and has interesting physical properties. In a certain temperature range, the polymer matrix collapses. This property could be useful in biomedicine, for drug transport, as an example: an enclosed drug could be released at a specific target in the body. Numerous other applications can also be imagined for these hybrid materials.

This new principle is very versatile: "By varying the type of polymer, the density of attachment points, and the chain length, we are able to produce hybrid nanotubes with tunable properties," says Biesalski. "We are now carrying out systematic studies to this end in our laboratory."

Topics

Organizations

Other news from the department science

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.