Acid-resistant bug doesn't give in to alcohol either

A chemist at Washington University in St. Louis has found surprisingly tough enzymes in a bacterium that "just says no to acid."

Acid resistance is a valued trait for both pills and human pathogens. The bacterium Acetobacter aceti makes unusually acid-resistant enzymes in spades, which could make the organism a source for new enzyme products and new directions in protein chemistry. A. aceti has been used for millennia to make vinegar, at least since an indirect reference in the Old Testament Book of Numbers to "vinegar made from wine." But not until recently did anybody study the unusual biochemical features of the organism that allow it to survive and even thrive in very acidic conditions.

"The thing that piqued our interest was that this organism has this weird growth habit of making vinegar from ethanol (alcohol), which means it's highly resistant to ethanol, which very few things grow in, and resistant to acetic acid (vinegar), which even fewer things grow in," said Joe Kappock, Ph.D., assistant professor of chemistry at Washington University in St. Louis. "Important enzymes in this bug resist acid in a way almost all organisms cannot, and we're trying to answer the question: 'How is this enzyme different?'" That answer, Kappock said, could reveal many new important insights.

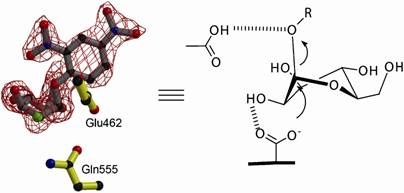

Specifically, Kappock and his research group study the enzyme citrate synthase, one of the oldest enzymes in a cell. Citrate synthase is important because it initiates the citric acid cycle, or Kreb's cycle, a biochemical pathway vitally important for energy production in the cells of organisms simple as bacteria and complex as humans.

There also are a couple of ways Acetobacter could produce industrially applicable information. "There are people who want to make more stable proteins," said Kappock. And: "There are increasing numbers of industrial processes that use enzymes, which are the ultimate green catalyst. The more things we can do with enzymes, the better for the environment, because they have no waste products." Enzymes already are used in products as diverse as laundry detergents and various medications.

According to Kappock, the more long-range goal is to involve insights from studies of this bacterium with the numerous diseases caused by protein mis-folding. Alzheimer's disease, Lou Gehrig's disease, and possibly even cataracts begin with mis-folded proteins. "A lot of times a mild acid-mediated unfolding of an enzyme precipitates these kinds of disease.", the chemist said. "Insights from these marvelous Acetobacter enzymes might lead to making more stable enzymes or elucidating ways to treat these debilitating diseases. ... What I'm hoping to get out of it is a better understanding of how proteins work. Our contribution is to find out how a couple of examples work and seeing if we can find general principles."

Topics

Organizations

Other news from the department science

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.

Most read news

More news from our other portals

Last viewed contents

Pharmacy

Green hydrogen: A cage structured material transforms into a performant catalyst - Very interesting class of materials for electrocatalysts discovered?

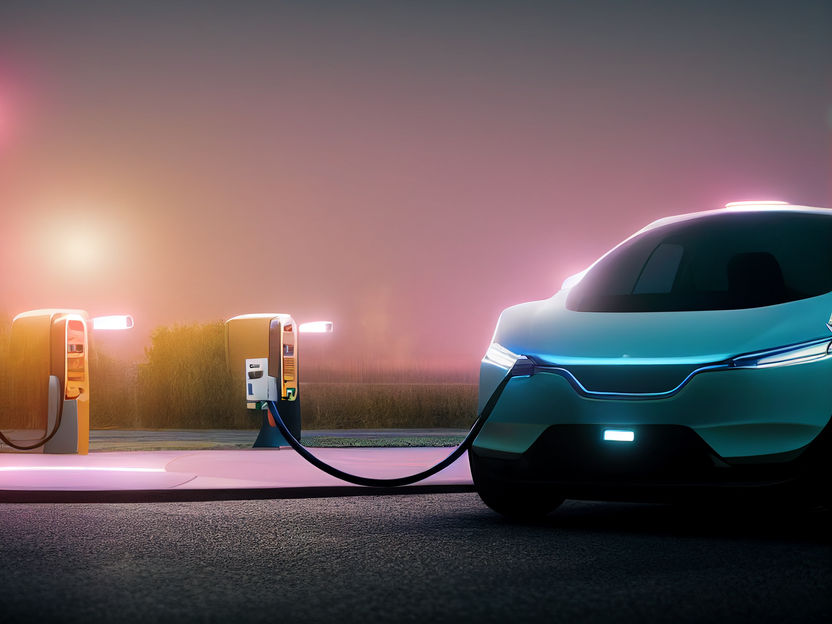

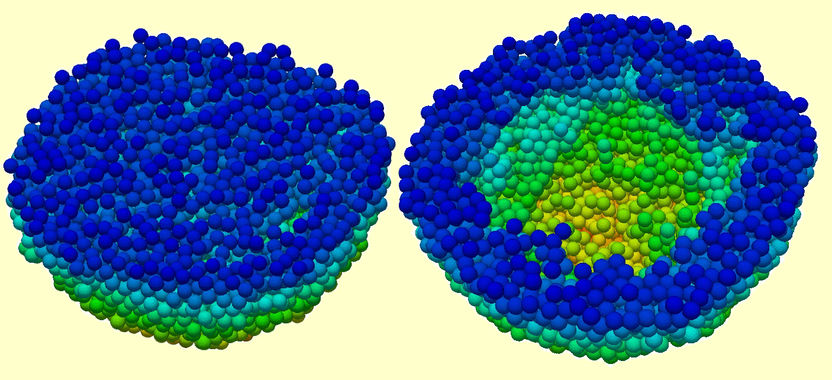

Watching lithium in real time could improve performance of EV battery materials - Researchers tracked the movement of lithium ions inside a promising new battery material

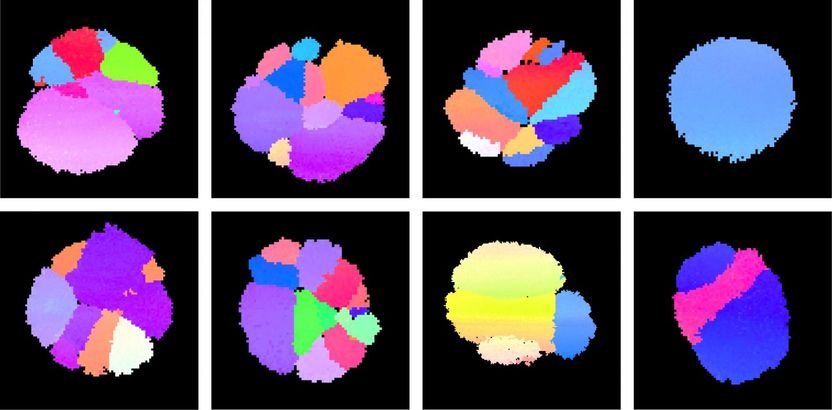

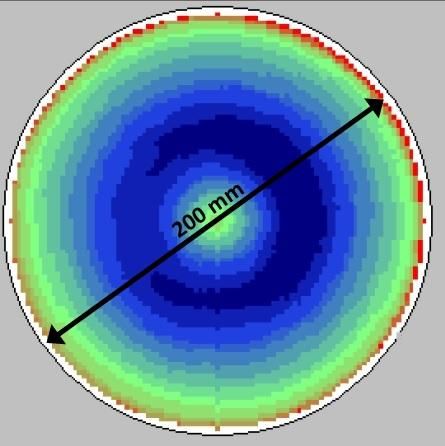

Spray drying the precision particle under the virtual magnifying glass

REACH is the dominant driver for substitution - more action is needed

Category:Materials_science_institutes

Single nanoparticle mapping paves the way for better nanotechnology

Electrons use the zebra crossing - Exotic Patterns of interacting electrons at the metal-insulator transition

GaN-on-Silicon for scalable high electron mobility transistors

Open_hearth_furnace