Color me purple, or red, or green, or ...

Imagine a miniature device that suffuses each room in your house with a different hue of the rainbow--purple for the living room, perhaps, blue for the bedroom, green for the kitchen. A team led by scientists at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) has, for the first time, developed nanoscale devices that divide incident white light into its component colors based on the direction of illumination, or directs these colors to a predetermined set of output angles.

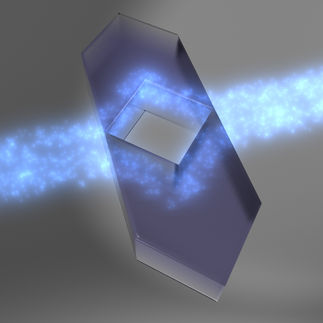

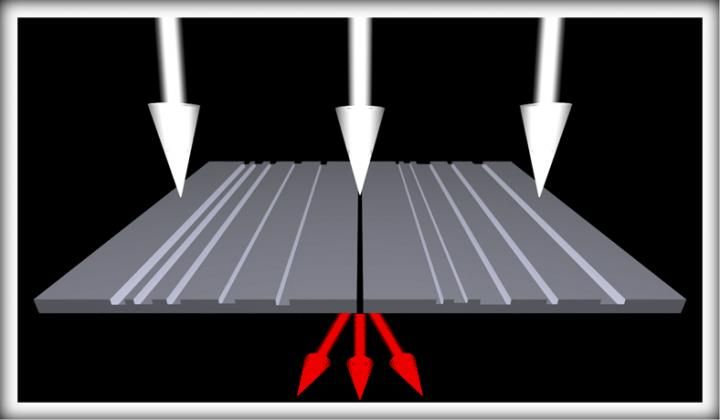

Schematic shows two different ways that white light interacts with a newly developed device, a directional color filter ruled with grooves that are not uniformly spaced. When white light illuminates the patterned side of the compact metal device at three different angles -- in this case, 0° degrees, 10° and 20° -- the device transmits light at red, green and blue wavelengths, respectively. When white light incident at any angle illuminates the device from the non-patterned side, it separates the light into the same three colors, and sends off each color in different directions corresponding to the same respective angles.

NIST

Viewed from afar, the device, referred to as a directional color filter, resembles a diffraction grating, a flat metal surface containing parallel grooves or slits that split light into different colors. However, unlike a grating, the nanometer-scale grooves etched into the opaque metal film are not periodic--not equally spaced. They are either a set of grooved lines or concentric circles that vary in spacing, much smaller than the wavelength of visible light. These properties shrink the size of the filter and allow it to perform many more functions than a grating can.

For instance, the device's nonuniform, or aperiodic, grid can be tailored to send a particular wavelength of light to any desired location. The filter has several promising applications, including generating closely spaced red, green and blue color pixels for displays, harvesting solar energy, sensing the direction of incoming light and measuring the thickness of ultrathin coatings placed atop the filter.

In addition to selectively filtering incoming white light based on the location of the source, the filter can also operate in a second way. By measuring the spectrum of colors passing through a filter custom-designed to deflect specific wavelengths of light at specific angles, researchers can pinpoint the location of an unknown source of light striking the device. This could be critical to determine if that source, for instance, is a laser aimed at an aircraft.

"Our directional filter, with its aperiodic architecture, can function in many ways that are fundamentally not achievable with a device such as a grating, which has a periodic structure," said NIST physicist Amit Agrawal. "With this custom-designed device, we are able to manipulate multiple wavelengths of light simultaneously."

Original publication

Other news from the department science

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.