Surprisingly ultraflat magnets

Advertisement

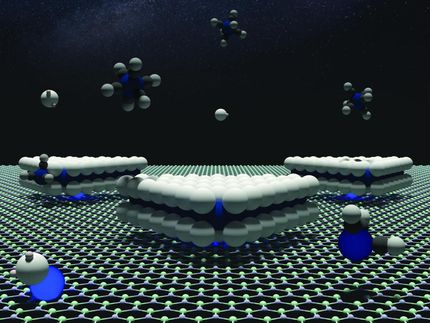

Substituting atoms in the process of making two-dimensional alloys not only allows them to be customized for applications but also can make them magnetic, according to Rice University scientists and their collaborators.

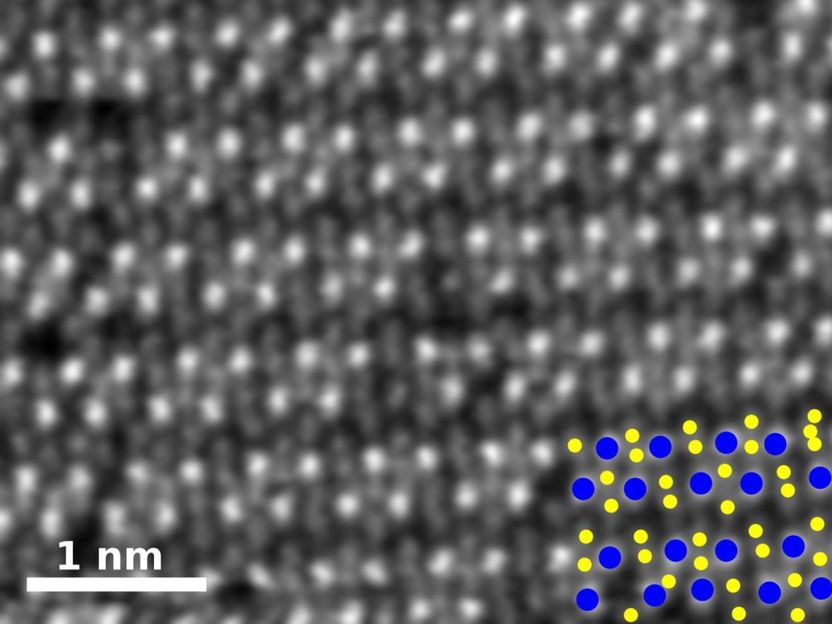

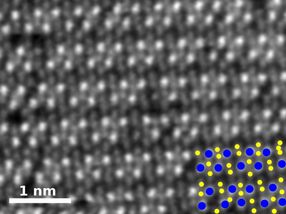

This is a high-angle annular dark-field image of pure rhenium diselenide. In the key at bottom right, rhenium atoms are blue and selenium atoms yellow.

Oak Ridge National Laboratory

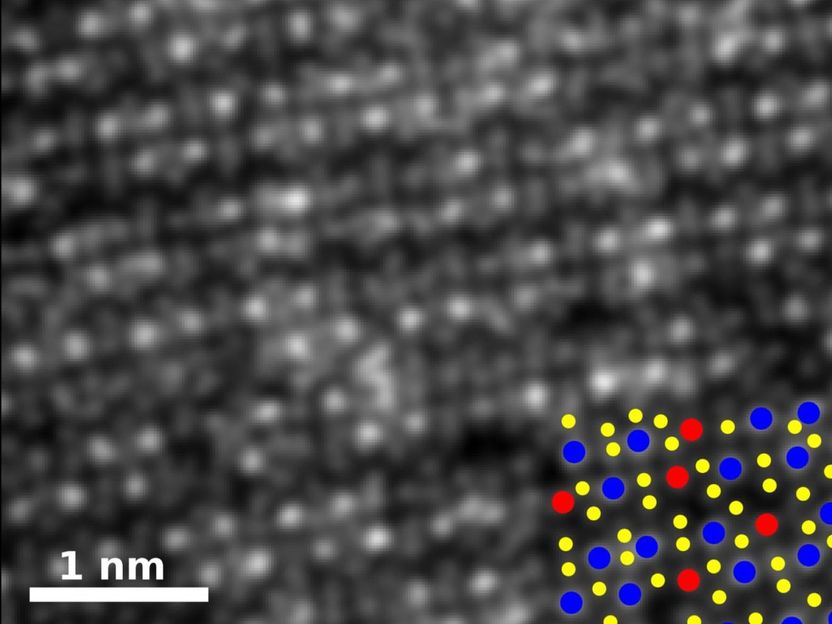

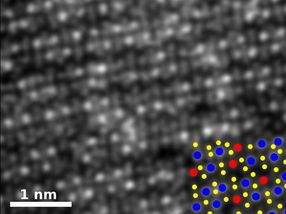

An image of rhenium-doped molybdenum diselenide shows how the material's atomic structure has been rearranged by the addition. The key shows the positions of rhenium atoms in blue, selenium in yellow and molybdenum in red.

Oak Ridge National Laboratory

Researchers at Rice, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, the University of Southern California (USC) and Kumamoto University in Japan used chemical vapor deposition (CVD) to make atom-thick sheets and, in the same step, tailor their properties by adding other elements through a process known as doping.

They discovered by surprise that they could also give the 2-D sheets magnetic properties.

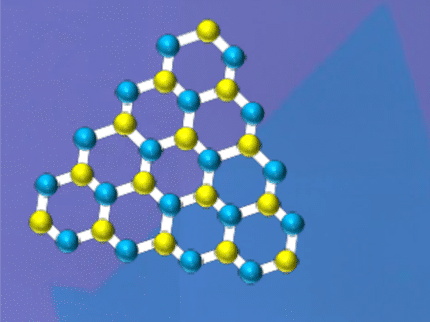

The labs worked with transition metal dichalcogenides, alloys that combine a transition metal and chalcogen atoms into a single material. Transition metals are stable elements that fall in the middle of the periodic table. Chalcogens include sulfur, selenium and tellurium, also neighbors to each other in the table.

By adding a dopant element to the mix during CVD, the researchers showed it was possible to rearrange the atoms on the resulting 2-D crystal sheets. They demonstrated several different configurations and found they could replace some atoms outright with the dopant. These physical changes led to changes in the mechanical and electronic properties of the flat crystals, said co-author and Rice postdoctoral researcher Chandra Sekhar Tiwary.

The Rice lab of Pulickel Ajayan led the project to test theories by USC researchers who calculated that doping the materials would force a phase transition in the 2-D crystals. The Rice team confirmed the theory that adding rhenium in various amounts to molybdenum diselenide during growth would allow them to tailor its properties by changing its atomic structure. The magnetic signatures were a bonus.

"Usually, when you make a magnetic material, you start with magnetic elements like iron or cobalt," said graduate student and co-lead author Amey Apte. "Rhenium, in bulk, is not a magnetic material, but it turns out it is in certain combinations at the atomic scale. It worked fantastically in this case."

The researchers said the magnetic properties they discovered could make the 2-D alloys of interest to those who design spintronic devices.

Original publication

Vidya Kochat, Amey Apte, Jordan A. Hachtel, Hiroyuki Kumazoe, Aravind Krishnamoorthy, Sandhya Susarla, Juan Carlos Idrobo, Fuyuki Shimojo, Priya Vashishta, Rajiv Kalia, Aiichiro Nakano, Chandra Sekhar Tiwary, Pulickel M. Ajayan; "Re Doping in 2D Transition Metal Dichalcogenides as a New Route to Tailor Structural Phases and Induced Magnetism"; Adv. Mater.; 2017