From iPad to iPaper

Investigation of paper-based electronics continues to advance, showing exciting signs of progress.

Imagine folding up a paper-thin computer tablet like a newspaper. It sounds like something out of a science fiction movie, but such flexible electronics are moving closer to reality.

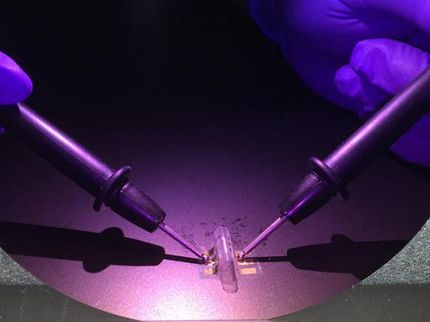

Portable paper solar cells based on foldable, lightweight, transparent, conductive cellulose nanofiber paper.

CC-BY Macmillan Publishers Ltd

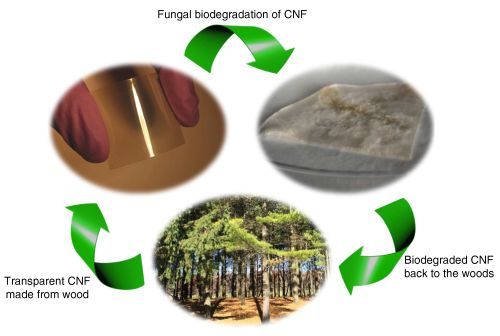

Cellulose, the building block of paper taken from plants, is an exciting alternative to the plastic, glass and silicon that currently make up most electronic devices. A key benefit is that it easily biodegrades in nature.

CC-BY Macmillan Publishers Ltd

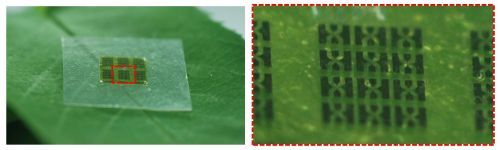

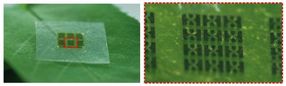

An array of heterojunction bipolar transistors on a cellulose nanofiber substrate put on a tree leaf. The right image shows the red-boxed area from the left image.

CC-BY Macmillan Publishers Ltd

Paper that is transparent and conducts electricity could have widespread applications, including foldable computers, transparent touch screens, and even digital camouflage clothing.

"With widespread and intensive efforts, low-cost and light-weight 'green' electronics fabricated on transparent nano paper substrate will provide new technologies impacting our daily life," state the review paper authors from Nanyang Technological University in Singapore.

Cellulose, the building block of paper taken from plants, is an exciting alternative to the plastic, glass and silicon that currently make up most electronic devices, including computers and mobile phones. Cellulose is renewable, biodegradable, strong, and lightweight. For the past 30 years, scientists have considered ways to combine these properties with electronics. Significant progress has been made in the past decade to manipulate the smallest plant fibers, called "nanocellulose", for use in electronics.

For example, researchers at Nanyang Technological University have made "nanopaper" out of nanocellulose and silver nanowires. It still conducted electricity after being folded in half 500 times. Some nanopapers have reached 90% transparency, while others are in the 80% range, similar to plastic. But, better than plastic, nanopapers degrade quickly. After metal electrodes are removed, nanopaper can be buried in soil and will fully degrade within a month. Researchers are still working on how to treat nanopapers that contain non-biodegradable materials, such as epoxy, to maintain their recyclability.

Many challenges remain before nanocellulose electronics become widespread. Currently, it is more expensive to produce pure nanopaper than glass or plastic. Cheaper preparation and fabrication methods are needed. Ideally, a common high-speed printing process used in electronic manufacturing called "roll to roll" can be adapted for nanocellulose. Also, the hydrophilic properties of cellulose make the items easy to degrade; this is desirable when it is time to dispose of them, but not during their operational life. The authors are optimistic that if these issues can be addressed, a wide range of electronics could soon be built from plants.

Original publication

Other news from the department science

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.