More solar power thanks to titanium

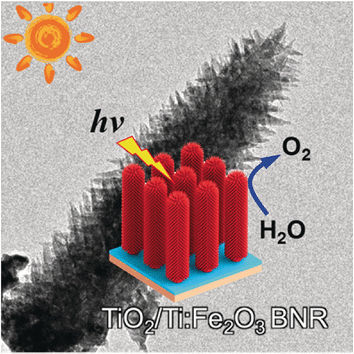

Earth-abundant, cheap metals are promising photocatalytic electrode materials in artificial photosynthesis. A team of Chinese scientists now reports that a thin layer of titania beneath hematite nanorods can boost the performance of the photoanode. As outlined in their report, the nanostructured electrode benefits from two separate effects. This design combining nanostructure with chemical doping may be exemplary for improved "green" photocatalytic systems.

© Wiley-VCH

With the help of a catalyst, sunlight can drive the oxidation of water to oxygen and the release of electrons for current generation, a process also called artificial photosynthesis. Iron oxide in the form of hematite is a convenient and cheap catalyst candidate, but the electrons set free by the chemical reaction tend to be trapped again and get lost; the electricity flow is inefficient. As a solution, Jinlong Gong from Tianjin University, China, introduced a nanometer-thin passivation layer of titania. Not only does this prevent charge recombination between the hematite electrode structure and the substrate, but it also provides the iron oxide with a considerable doping source to increase its charge-carrier density, a highly promising effect for photoelectric applications.

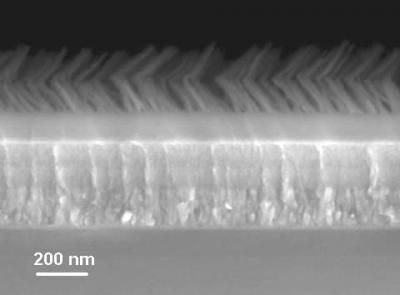

Hematite may be an abundant material (iron ore), but despite its photocatalytic advantages like photostability and good energetic preconditions, scientists still struggle with its sluggish kinetics and poor electrical conductivity. Nanostructured hematite may be one solution. The hematite photocatalysts are grown on conductive glass substrates in nanorod arrays, which are further furnished with branchlets to obtain a bushy, dendritic shape. This branched nanorod structure greatly enlarges the surface to promote the water-oxidation reaction, but the problem of charge recombination, especially at the hematite-substrate interface, is not solved.

Therefore, Gong and his colleagues grew dendritic hematite nanorods on an interlayer of titanium dioxide, which by itself is a photoactive material. If sufficiently thin, the coated structure can both prevent charge recombination and provide conductivity, but this was not the only intention the scientists had. "The titanium dioxide interlayer was considered to act as a titanium cation source to dope hematite," they argued. Doping here means to increase the charge-carrier density in the photocatalyst by bringing in more positive centers and boost the electrical conductivity.

Both effects, passivation and doping, indeed produced a more than four times higher photocurrent under standardized conditions. The addition of an iron hydroxide co-catalyst pushed the photocurrent density even further to a value more than five times above that of the undoped system. This design combining cheap materials, few preparation steps, and enhanced electrical performance may be exemplary for improved systems in green artificial photosynthesis.

Original publication

Other news from the department science

Most read news

More news from our other portals

See the theme worlds for related content

Topic world Synthesis

Chemical synthesis is at the heart of modern chemistry and enables the targeted production of molecules with specific properties. By combining starting materials in defined reaction conditions, chemists can create a wide range of compounds, from simple molecules to complex active ingredients.

Topic world Synthesis

Chemical synthesis is at the heart of modern chemistry and enables the targeted production of molecules with specific properties. By combining starting materials in defined reaction conditions, chemists can create a wide range of compounds, from simple molecules to complex active ingredients.