The first light atomic nucleus with a second face

To some degree of approximation, atomic nuclei look like spheres which in most cases are distorted to a greater or lesser extent. When the nucleus is excited, its shape may change, but only for an extremely brief moment, after which it returns to its original state. A relatively permanent 'second faceâ' of atomic nuclei has so far only been observed in the most massive elements. In a spectacular experiment, physicists from Poland, Italy, Japan, Belgium and Romania have for the first time succeeded in registering it in a nucleus recognized as being light.

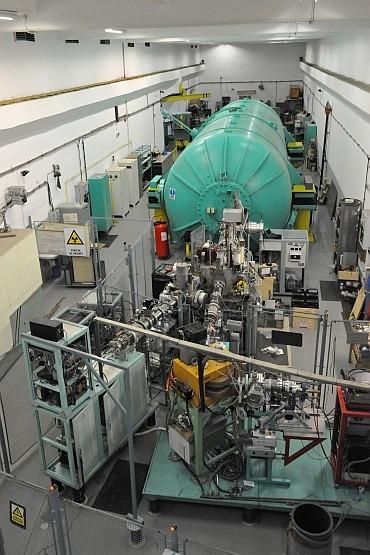

In an experiment performed at the Romanian accelerator centre IFIN-HH, an international team of physicists observed a 'second face' of the nickel-66 nuclei: a relatively stable excited state in which the shape of nucleus is changed.

IFIN-HH

Atomic nuclei are able to change their shape depending on the amount of energy they possess or the speed at which they spin. Changes related only to the addition of energy (and thus not taking into account spin) are relatively stable only in nuclei of the most massive elements. Now, it turns out that the nuclei of much lighter elements, such as nickel, can also persist a little longer in their new shape. The discovery was made by a team of scientists from the Italian Universita' degli Studi di Milano (UniMi), the Institute of Nuclear Physics of the Polish Academy of Sciences (IFJ PAN) in Cracow, the Romanian National Institute of Physics and Nuclear Engineering (IFIN-HH), the Japanese University of Tokyo and the Belgian University of Brussels. The calculations necessary for the preparation of the experiment proved to be so complex that a computer infrastructure of about one million processors was required to perform them.

Constructed of protons and neutrons, atomic nuclei are generally considered to be spherical structures. However, in reality, most atomic nuclei are structures that are deformed to a greater or lesser extent: flattened or elongated along one, two, or sometimes even all three axes. What's more, just as a ball flattens more or less depending on the force exerted on it by a hand, so atomic nuclei can change their deformation depending on the amount of energy they possess, even when they are not spinning.

"When an atomic nucleus is supplied with the right amount of energy, it can transition into a state with a different shape deformation than is typical for the basic state. This new deformation - illustratively speaking: its new face - is, however, very unstable. Just like a ball returns to its original shape after the hand that has distorted it is removed, so the nucleus returns to its original form, but it does so much, much faster, in billionths of a billionth of a second or an even shorter time. So, instead of talking about the second face of the atomic nucleus, it's probably better to talk about just a grimace", explains Prof. Bogdan Fornal (IFJ PAN), whose research team included Dr. Natalia Cieplicka-Orynczak, Dr. Lukasz Iskra and Dr. Mateusz Krzysiek.

In the last few decades, evidence has been gathered confirming that a relatively stable state with a deformed shape is present in the nuclei of a small number of elements. Measurements have shown that the nuclei of some actinides - elements with atomic numbers from 89 (actinium) to 103 (lawrencium) - are capable of maintaining their 'second face' even tens of millions of times longer than other nuclei. Actinides are elements with a total number of protons and neutrons well above 200, so very massive. Up to now, among the non-spinning nuclei of lighter elements an excited state with a deformed shape, characterized by increased stability, has never been observed.

"Together with Professor Michel Sferrazza, now working at the University of Brussels, already at the beginning of the 1990s, we pointed out that two theoretical models of nuclear excitation predict the existence of relatively stable states with deformed shapes in the nuclei of light elements. Shortly, a third model appeared which also led to similar conclusions. Our attention was drawn to nickel-66, because it was present in the predictions of all three models", recalls Prof. Fornal.

The possibility of experimentally searching for relatively stable states with deformed shapes in the Ni-66 nucleus has, however, only emerged recently. The new experimental method, proposed by Prof. Silvia Leoni (UniMi), combined with the computationally extremely sophisticated Monte Carlo shell model developed by the Tokyo University theorists, enabled the design of appropriate, accurate measurements. The experiment was carried out at the 9 MV FN Pelletron Tandem accelerator operating in the Romanian National Institute of Physics and Nuclear Engineering (IFIN-HH).

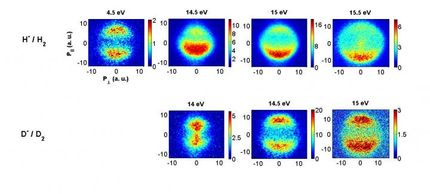

In the experiment in Bucharest, a target of nickel-64 was fired with nuclei of oxygen-18. Relative to oxygen-16, which is the main (99.76%) isotope of atmospheric oxygen, these nuclei contain two additional neutrons. During the collisions, both the excess neutrons can be transferred to the nickel nuclei, resulting in the creation of nickel-66, the basic shape of which is almost an ideal sphere. With properly selected collision energies, a small portion of the Ni-66 nuclei thus formed achieve a certain state with a deformed shape which, as measurements showed, proved to be slightly more stable than all other excited states associated with significant deformation. In other words, the nucleus was in a local, deep minimum of potential.

"The extension of life span measured by us of the deformed shape of the Ni-66 nucleus is not as spectacular as that of the actinides, where it reached tens of millions of times. We recorded only five-fold growth. Nevertheless, the measurement was exceptional, because it was the first observation of its kind in light nuclei", concludes Prof. Fornal and stresses that the measured delay times of return to the basic state correspond to an acceptable extent with the values provided by the new theoretical model, which further enhances the attainment of the achievement. None of the earlier models of nuclear structure allowed for such detailed predictions. This suggests that the new theoretical approach should be helpful in describing several thousand nuclei that have not yet been discovered.