Spinning electrons open the door to future hybrid electronics

A discovery of how to control and transfer spinning electrons paves the way for novel hybrid devices that could outperform existing semiconductor electronics. In a study published in Nature Communications, researchers at Linkoping University in Sweden demonstrate how to combine a commonly used semiconductor with a topological insulator, a recently discovered state of matter with unique electrical properties.

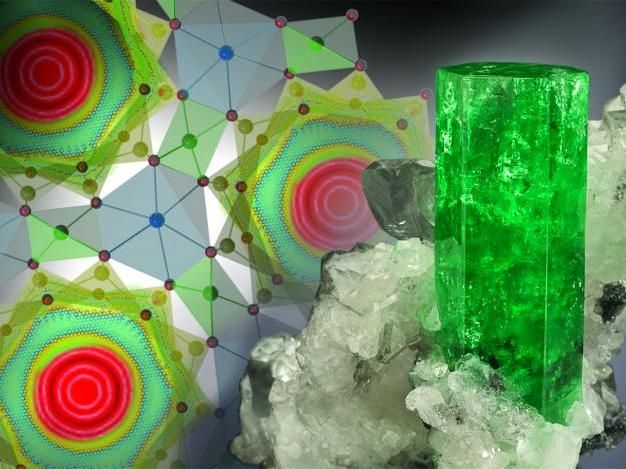

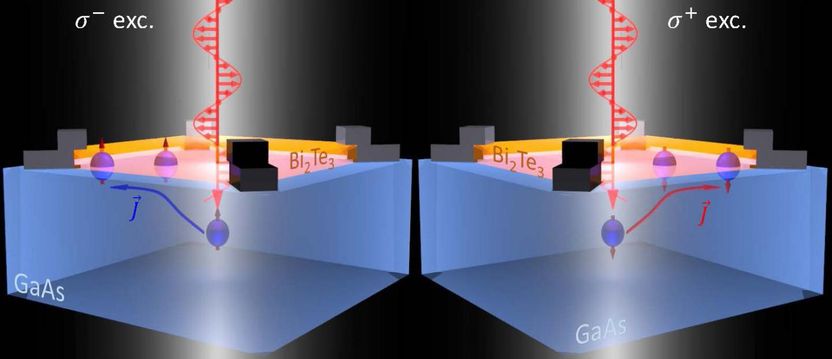

The researchers have taken the first step towards transferring spin-oriented electrons between a topological insulator (orange layer) and a conventional semiconductor (blue layer).

Weimin Chen

Just as the Earth spins around its own axis, so does an electron, in a clockwise or counter-clockwise direction. "Spintronics" is the name used to describe technologies that exploit both the spin and the charge of the electron. Current applications are limited, and the technology is mainly used in computer hard drives. Spintronics promises great advantages over conventional electronics, including lower power consumption and higher speed.

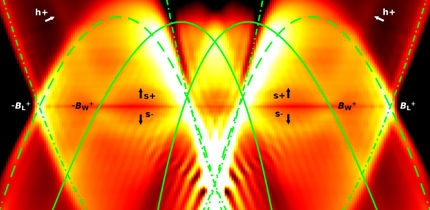

In terms of electrical conduction, natural materials are classified into three categories: conductors, semiconductors and insulators. Researchers have recently discovered an exotic phase of matter known as "topological insulators", which is an insulator inside, but a conductor on the surface. One of the most striking properties of topological insulators is that an electron must travel in a specific direction along the surface of the material, determined by its spin direction. This property is known as "spin-momentum locking".

"The surface of a topological insulator is like a well-organised divided highway for electrons, where electrons having one spin direction travel in one direction, while electrons with the opposite spin direction travel in the opposite direction. They can travel fast in their designated directions without colliding and without losing energy," says Yuqing Huang, Ph D student at the Department of Physics, Chemistry and Biology (IFM) at Linkoping University.

These properties make topological insulators promising for spintronic applications. However, one key question is how to generate and manipulate the surface spin current in topological insulators.

The research team behind the current study has now taken the first step towards transferring spin-oriented electrons between a topological insulator and a conventional semiconductor. They generated electrons with the same spin in gallium arsenide, GaAs, a semiconductor commonly used in electronics. To achieve this, they used circularly polarised light, in which the electric field rotates either clockwise or counter-clockwise when seen in the direction of travel of the light. The spin-polarised electrons could then be transferred from GaAs to a topological insulator, to generate a directional electric current on the surface. The researchers could control the orientation of spin of the electrons, and the direction and the strength of the electric current in the topological insulator bismuth telluride, Bi2Te3. This flexibility has according to the researchers not been available before. All of this was accomplished without applying an external electric voltage, demonstrating the potential of efficient conversion from light energy to electricity. The findings are significant for the design of novel spintronic devices that exploit the interaction of matter with light, a technology known as "opto-spintronics".

"We combine the superior optical properties of GaAs with the unique electrical properties of a topological insulator. This has given us new ideas for designing opto-spintronic devices that can be used for efficient and robust information storage, exchange, processing and read-out in future information technology," says Professor Weimin Chen, who has led the study.

Original publication

Other news from the department science

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.

Most read news

More news from our other portals

Last viewed contents

James_Fraser_Stoddart

Diet_and_cancer

High-value Opportunities for Lignin - Recent technological breakthroughs in lignin extraction and conversion could change the course of the oil-based chemical industry

Quinuclidone

2024_aluminum

Organoborane

GE Osmonics SAS - Le Mee sur Seine, France

DSM invests in biomaterials company Oxford Performance Materials

VSEPR & Shapes of Molecules

Nanogel

Category:Niobium_compounds