New-generation material removes iodine from water

Researchers at Dartmouth College have developed a new material that scrubs iodine from water for the first time. The breakthrough could hold the key to cleaning radioactive waste in nuclear reactors and after nuclear accidents like the 2011 Fukushima disaster.

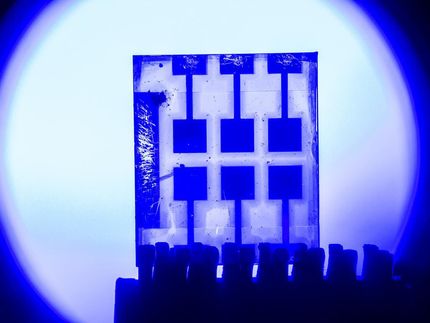

Iodine is removed from an aqueous solution after the addition of HCOF-1.

Chenfeng Ke / Dartmouth College

The new-generation microporous material designed at Dartmouth is the result of chemically stitching small organic molecules to form a framework that scrubs the isotope from water.

"There is simply no cost-effective way of removing radioactive iodine from water, but current methods of letting the ocean or rivers dilute the dangerous contaminant are just too risky," said Chenfeng Ke, assistant professor in the Department of Chemistry at Dartmouth College . "We are not sure how efficient this process will be, but this is definitely the first step toward knowing its true potential."

Radioactive iodine is a common byproduct of nuclear fission and is a pollutant in nuclear disasters including the recent meltdown in Japan and the 1986 Chernobyl disaster. While removing iodine in the gas phase is relatively common, iodine has never been removed from water prior to the Dartmouth research.

"We have solved the stubborn scientific problem of making a porous material with high crystallinity that is also chemically stable in strong acidic or basic water," said Ke, the principle investigator for the research. "In the process of developing a material that combats environmental pollution, we also created a method that paves the way for a new class of porous organic materials."

The research describes how researchers used sunlight to crosslink small molecules in large crystals to produce the new material. The approach is different from the traditional method of combining molecules in one pot.

During the research, concentrations of iodine were reduced from 288 ppm to 18 ppm within 30 minutes, and below 1 ppm after 24 hours. The soft stitching technique resulted in a breathable material that changed shape and adsorbed more than double its weight of iodine. The compound was also found to be elastic, making it reusable and potentially even more valuable for environmental cleanup.

According to Ke, the compound could be used in a manner similar to applying salt to contaminated water. Since it is lighter than water, the material floats to adsorb iodine and then sinks as it becomes heavier. After taking on the iodine, the compound can be collected, cleaned and reused while the radioactive elements are sent for storage.

The lab research used non-radioactive iodine in salted water for the experiment, but researchers say that it will also work in real-world conditions. Ke and his team hope that through continued testing the material will prove to be effective against cesium and other radioactive contaminants associated with nuclear plants.

"It would be ideal to scrub more radioactive species other than iodine--you would want to scrub all of the radioactive material in one go," said Ke.

Researchers at Dartmouth's Ke Functional Materials Group are also hopeful that the technique can be used to create materials to target other types of inorganic and organic pollutants, particularly antibiotics in water supplies that can lead to the creation of super-resistant microorganisms.

Original publication

Other news from the department science

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.

Most read news

More news from our other portals

Last viewed contents

Whale_oil

Hansa_yellow

WITec takes over majority of optical measurement solutions provider omt gmbh - Industrial applications and inline process control in focus

Microwave_plasma

Researchers reveal elusive bottleneck holding back global effort to convert carbon dioxide waste into usable products

Category:Silver_compounds