Team highlights work on tuning block polymers for nanostructured systems

High-performance materials are enabling major advances in a wide range of applications from energy generation and digital information storage to disease screening and medical devices.

Block polymers, which are two or more polymer chains with different properties linked together, show great promise for many of these applications, and a research group at the University of Delaware has made significant strides in their development over the past several years.

"We are using synthesis, processing and characterization methods that are robust and widely applicable, with an eye toward scaling these methods to facilitate the future industrial adoption of block polymers," says Thomas H. Epps, III, who leads the group.

Epps, who is the Thomas and Kipp Gutshall Professor of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering and professor of Materials Science and Engineering at UD, and two of his graduate students, Melody Morris and Thomas Gartner, recently published an article highlighting this work. The piece was a "Talent" submission, a unique article type dedicated to young scientists.

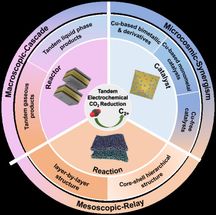

The article highlights the Epps group's work aimed at tuning and characterizing block polymers in bulk and thin film geometries. The group has leveraged expertise in polymer chemistry, polymer physics, chemical engineering and materials science to manipulate the phase behavior, thermal transitions and mechanical and transport properties of block polymers to optimize materials design.

"Our goal was to show how a truly multidisciplinary approach can help solve problems in the development of next-generation materials -- a development that requires simultaneous consideration of structure, properties and processing," Epps says.

He points to battery technologies as an example.

Battery membranes, and the associated electrolytes, used to enable ion transport for energy storage and generation applications can offer high performance in terms of rapid charging, long lifespan and minimal self-discharge. However, these benefits often are accompanied by safety -- for example, explosion and fire -- and environmental concerns.

"We want to design these membranes so that we can achieve the same, or better, performance as current technologies while also reducing the potential for explosions and other catastrophic failures," Epps says. "At the same time, we'd like to develop the ability to process these materials at lower temperatures and with decreased amounts of harmful solvents. In other words, we want to reduce defects and mitigate threats to the environment through control of fabrication."

One approach the Epps group is taking is the use of nanoscale structures to improve both device performance and processing. To do this, they have developed high-throughput and combinatorial computational methods that allow nanoscale structures to be visualized with relatively low-cost optical techniques.

"Basically, this approach enables us to minimize the number of samples that need to be measured with expensive techniques such as atomic force microscopy and transmission electron microscopy," Epps says.

The group also has developed universal design rules -- that is, those that are applicable to a number of different types of surfaces and polymers -- to understand key factors that link surface characteristics to nanostructure formation.

"These rules enable us to predict which polymers will work well with which surfaces, so, for example, we can create self-cleaning coatings that can resist fingerprint smudges on touchscreens," Epps says.

Epps is also leading an effort to do nanoscale patterning with block polymers as a low-cost alternative to lithographic approaches currently used to make electronic devices.

"With all of this work, I think the things that set us apart are the universal approaches, the inclusion of joint experiment and theory efforts, and our unique focus on combined chemistry, physics, and processing knowledge to accelerate materials design," he says.

Original publication

Other news from the department science

These products might interest you

Spinsolve Benchtop NMR by Magritek

Spinsolve Benchtop NMR

Spinsolve is a revolutionary multinuclear NMR spectrometer that provides the best performance

Eclipse by Wyatt Technology

FFF-MALS system for separation and characterization of macromolecules and nanoparticles

The latest and most innovative FFF system designed for highest usability, robustness and data quality

HYPERION II by Bruker

FT-IR and IR laser imaging (QCL) microscope for research and development

Analyze macroscopic samples with microscopic resolution (5 µm) in seconds

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.

Most read news

More news from our other portals

Last viewed contents

Lamb-Oseen_vortex

Tetraoxygen

Costa's_minimal_surface

Clariant focusing on profitable growth with stringent cost management

Borealis Fast-Tracks Innovation with University of Leoben

New sensor system improves detection of lead, heavy metals - PNNL develops inexpensive portable detection system for rapid, accurate analysis of toxic metals

American_Society_of_Health-System_Pharmacists

Apokjeden

Panethite

BASF Implements AspenTech's Manufacturing Information Management Solution