New mechanical metamaterials can block symmetry of motion

Engineers and scientists at The University of Texas at Austin and the AMOLF institute in the Netherlands have invented the first mechanical metamaterials that easily transfer motion effortlessly in one direction while blocking it in the other. The material can be thought of as a mechanical one-way shield that blocks energy from coming in but easily transmits it going out the other side.

This is an artist's rendering of mechanical metamaterials.

Cockrell School of Engineering

The researchers developed the first nonreciprocal mechanical materials using metamaterials, which are synthetic materials with properties that cannot be found in nature.

Breaking the symmetry of motion may enable greater control on mechanical systems and improved efficiency. These nonreciprocal metamaterials can potentially be used to realize new types of mechanical devices: for example, actuators (components of a machine that are responsible for moving or controlling a mechanism) and other devices that could improve energy absorption, conversion and harvesting, soft robotics and prosthetics.

The researchers' breakthrough lies in the ability to overcome reciprocity, a fundamental principle governing many physical systems, which ensures that we get the same response when we push an arbitrary structure from opposite directions. This principle governs how signals of various forms travel in space and explains why, if we can send a radio or an acoustic signal, we can also receive it. In mechanics, reciprocity implies that motion through an object is transmitted symmetrically: If by pushing on side A we move side B by a certain amount, we can expect the same motion at side A when pushing B.

"The mechanical metamaterials we created provide new elements in the palette that material scientists can use in order to design mechanical structures," said Andrea Alu, a professor in the Cockrell School of Engineering and co-author of the paper. "This can be of extreme interest for applications in which it is desirable to break the natural symmetry with which the displacement of molecules travels in the microstructure of a material."

During the past couple of years, Alu, along with Cockrell School research scientist Dimitrios Sounas and other members of their research team, have made exciting breakthroughs in the area of nonreciprocal devices for electromagnetics and acoustics, including the realization of first-of-their-kind nonreciprocal devices for sound, radio waves and light. While visiting the institute AMOLF in the Netherlands, they started a fruitful collaboration with Corentin Coulais, an AMOLF researcher, who recently has been developing mechanical metamaterials. Their close interaction led to this breakthrough.

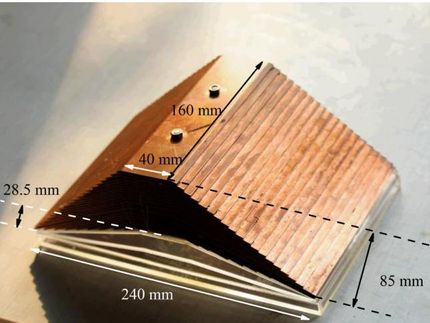

The researchers first created a rubber-made, centimeter-scale metamaterial with a specifically tailored fishbone skeleton design. They tailored its design to meet the main conditions to break reciprocity, namely asymmetry and a response that is not linearly proportional to the exerted force.

"This structure provided us inspiration for the design of a second metamaterial, with unusually strong nonreciprocal properties," Coulais said. "By substituting the simple geometrical elements of the fishbone metamaterial with a more intricate architecture made of connected squares and diamonds, we found that we can break very strongly the conditions for reciprocity, and we can achieve a very large nonreciprocal response."

The material's structure is a lattice of squares and diamonds that is completely homogeneous throughout the sample, like an ordinary material. However, each unit of the lattice is slightly tilted in a certain way, and this subtle difference dramatically controls the way the metamaterial responds to external stimuli.

"The metamaterial as a whole reacts asymmetrically, with one very rigid side and one very soft side," Sounas said. "The relation between the unit asymmetry and the soft side location can be predicted by a very generic mathematical framework called topology. Here, when the architectural units lean left, the right side of the metamaterial will be very soft, and vice-versa."

When the researchers apply a force on the soft side of the metamaterial, it easily induces rotations of the squares and diamonds within the structure, but only in the near vicinity of the pressure point, and the effect on the other side is small. Conversely, when they apply the same force on the rigid side, the motion propagates and is amplified throughout the material, with a large effect at the other side. As a result, pushing from the left or from the right results in very different responses, yielding a large nonreciprocity even for small applied forces.

The team is looking forward to leveraging these topological mechanical metamaterials for various applications, optimizing them, and carving devices out of them for applications in soft robotics, prosthetics and energy harvesting.