How X-rays in matter create genetoxic low-energy electrons

Researchers led by Kiyoshi Ueda of Tohoku University have investigated what X-rays in matter really do and identified a new mechanism of producing low-energy free electrons. Since the low-energy electrons cause damage to the matter, the identified process might be important in understanding and designing radiation treatment of illnesses.

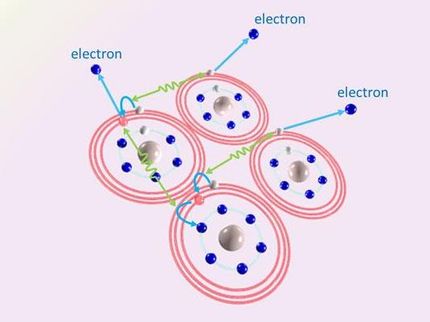

Scientists have elucidated a novel mechanism of electron emission from matter caused by X-rays. In the studied model system, X-rays produce the doubly-charged particle (Ne2+), which catches an electron from one of the neighboring atoms (Kr), transferring the energy to the other and releasing another electron.

Kiyoshi Ueda

X-rays are one of the most important diagnostic tools in medicine, biology and the material sciences, as they may penetrate deep into material which is opaque to the human eye. Their passage through a sample, however, can have side effects, as the absorption of X-rays deposes energy in deep layers of the sample. In extreme cases, the application of X-rays is limited by these side effects, known as 'radiation damage'. Medicine is one area in which the absorbed X-ray dose must be minimized.

Surprisingly, it is unclear what happens when an X-ray is absorbed, for example, in biological tissue consisting of water, biomolecules and some metal atoms. One reason for this is that the first few steps of reactions after the absorption of an X-ray, happen extremely fast, within 10-100 femtoseconds. A femtosecond is the SI unit of time equal to 10?15. To put it another way, it's one millionth of one billionth of a second.

Within this time, in a complex cascade of events, several electrons are emitted, and positively charged reactive particles (ions) are created. Most experiments done up to now were only able to characterize this final state a long time after the cascading reaction was completed. However, it is the precise understanding of the intermediate steps that is very important for the prediction and design of radiation effects in matter.

The team has now carried out an experiment that took an unprecedented detailed view of the first few hundred fs after absorption of an X-ray by matter.

In a biological system, a lot of water molecules are flexibly arranged around the biologically functional molecules, without strongly binding to them.

As a model system for that, a flexible, weakly bonded aggregate of two different noble gases, Ne and Kr, was created by cooling them to extremely low temperatures. These Ne-Kr clusters were then exposed to pulsed X-rays of the SPring-8 synchrotron radiation source which, under the conditions chosen for the experiment, preferentially ionized Ne atoms.

By using an advanced experimental set-up, the team was able to record all electrons and ions that were created at every X-ray absorption event. They found that just a few hundred fs after the initial ionization, the Ne atom that had absorbed the x-ray, as well as two neighboring Kr atoms, were all in an ionized, positively charged state.

The mechanism by which this ultrafast charge redistribution proceeds, proposed theoretically by research team member Lorenz Cederbaum, has been named the 'Electron Transfer Mediated Decay' (ETMD). It consists of electron transfer to the originally ionized Ne atom matched by energy transfer away from the Ne, which leads to ionization of the second Kr atom nearby. The experiment clearly demonstrates that highly localized charge produced by X-rays in matter, redistributes over many atomic sites in a surprisingly short time.

Kiyoshi Ueda says: 'We believe that understanding X-ray initiated processes on a microscopic level will lead to new insights across the disciplines of physics, biology and chemistry.'

Original publication

D. You, H. Fukuzawa, Y. Sakakibara, T. Takanashi, Y. Ito, G. G. Maliyar, K. Motomura, K. Nagaya, T. Nishiyama, K. Asa, Y. Sato, N. Saito, M. Oura, M. Schöffler, G. Kastirke, U. Hergenhahn, V. Stumpf, K. Gokhberg, A. I. Kuleff, L. S. Cederbaum & K Ueda; "Charge transfer to ground-state ions produces free electrons"; Nature Comm.; 2017

Most read news

Original publication

D. You, H. Fukuzawa, Y. Sakakibara, T. Takanashi, Y. Ito, G. G. Maliyar, K. Motomura, K. Nagaya, T. Nishiyama, K. Asa, Y. Sato, N. Saito, M. Oura, M. Schöffler, G. Kastirke, U. Hergenhahn, V. Stumpf, K. Gokhberg, A. I. Kuleff, L. S. Cederbaum & K Ueda; "Charge transfer to ground-state ions produces free electrons"; Nature Comm.; 2017

Other news from the department science

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.