Metallic hydrogen, once theory, becomes reality

Nearly a century after it was theorized, Harvard scientists have succeeded in creating the rarest - and potentially one of the most valuable - materials on the planet.

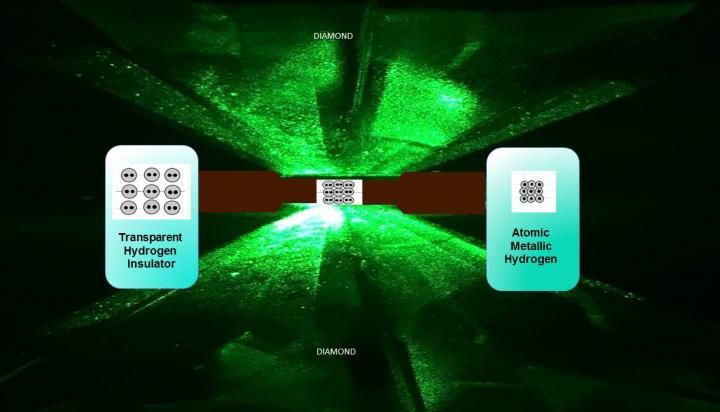

Image of diamond anvils compressing molecular hydrogen. At higher pressure the sample converts to atomic hydrogen, as shown on the right. This material relates to a paper that appeared in the Jan. 27 2017, issue of Science, published by AAAS. The paper, by R.P. Dias at Harvard University in Cambridge, MA, and colleagues was titled, "Observation of the Wigner-Huntington transition to metallic hydrogen."

R. Dias and I.F. Silvera

The material - atomic metallic hydrogen - was created by Thomas D. Cabot Professor of the Natural Sciences Isaac Silvera and post-doctoral fellow Ranga Dias. In addition to helping scientists answer fundamental questions about the nature of matter, the material is theorized to have a wide range of applications, including as a room-temperature superconductor.

"This is the holy grail of high-pressure physics," Silvera said. "It's the first-ever sample of metallic hydrogen on Earth, so when you're looking at it, you're looking at something that's never existed before."

To create it, Silvera and Dias squeezed a tiny hydrogen sample at 495 gigapascal, or more than 71.7 million pounds-per-square inch - greater than the pressure at the center of the Earth. At those extreme pressures, Silvera explained, solid molecular hydrogen -which consists of molecules on the lattice sites of the solid - breaks down, and the tightly bound molecules dissociate to transforms into atomic hydrogen, which is a metal.

While the work offers an important new window into understanding the general properties of hydrogen, it also offers tantalizing hints at potentially revolutionary new materials.

"One prediction that's very important is metallic hydrogen is predicted to be meta-stable," Silvera said. "That means if you take the pressure off, it will stay metallic, similar to the way diamonds form from graphite under intense heat and pressure, but remains a diamond when that pressure and heat is removed."

Understanding whether the material is stable is important, Silvera said, because predictions suggest metallic hydrogen could act as a superconductor at room temperatures.

"That would be revolutionary," he said. "As much as 15 percent of energy is lost to dissipation during transmission, so if you could make wires from this material and use them in the electrical grid, it could change that story."

Among the holy grails of physics, a room temperature superconductor, Dias said, could radically change our transportation system, making magnetic levitation of high-speed trains possible, as well as making electric cars more efficient and improving the performance of many electronic devices.

The material could also provide major improvements in energy production and storage - because superconductors have zero resistance energy could be stored by maintaining currents in superconducting coils, and then be used when needed.

Though it has the potential to transform life on Earth, metallic hydrogen could also play a key role in helping humans explore the far reaches of space, as the most powerful rocket propellant yet discovered.

"It takes a tremendous amount of energy to make metallic hydrogen," Silvera explained. "And if you convert it back to molecular hydrogen, all that energy is released, so it would make it the most powerful rocket propellant known to man, and could revolutionize rocketry."

The most powerful fuels in use today are characterized by a "specific impulse" - a measure, in seconds, of how fast a propellant is fired from the back of a rocket - of 450 seconds. The specific impulse for metallic hydrogen, by comparison, is theorized to be 1,700 seconds.

"That would easily allow you to explore the outer planets," Silvera said. "We would be able to put rockets into orbit with only one stage, versus two, and could send up larger payloads, so it could be very important."

To create the new material, Silvera and Dias turned to one of the hardest materials on Earth - diamond.

But rather than natural diamond, Silvera and Dias used two small pieces of carefully polished synthetic diamond which were then treated to make them even tougher and then mounted opposite each other in a device known as a diamond anvil cell.

"Diamonds are polished with diamond powder, and that can gouge out carbon from the surface," Silvera said. "When we looked at the diamond using atomic force microscopy, we found defects, which could cause it to weaken and break."

The solution, he said, was to use a reactive ion etching process to shave a tiny layer - just five microns thick, or about one-tenth of a human hair - from the diamond's surface. The diamonds were then coated with a thin layer of alumina to prevent the hydrogen from diffusing into their crystal structure and embrittling them.

After more than four decades of work on metallic hydrogen, and nearly a century after it was first theorized, seeing the material for the first time, Silvera said, was thrilling.

"It was really exciting," he said. "Ranga was running the experiment, and we thought we might get there, but when he called me and said, 'The sample is shining,' I went running down there, and it was metallic hydrogen.

"I immediately said we have to make the measurements to confirm it, so we rearranged the lab...and that's what we did," he said. "It's a tremendous achievement, and even if it only exists in this diamond anvil cell at high pressure, it's a very fundamental and transformative discovery."