Explaining how 2-D materials break at the atomic level

Cracks sank the 'unsinkable' Titanic; decrease the performance of touchscreens and erode teeth. We are familiar with cracks in big or small three-dimensional (3D) objects, but how do thin two-dimensional (2D) materials crack? 2D materials, like molybdenum disulfide (MoS2), have emerged as an important asset for future electronic and photoelectric devices. However, the mechanical properties of 2D materials are expected to differ greatly from 3D materials. Scientists at the Center for Integrated Nanostructure Physics (CINAP), within the Institute for Basic Science (IBS) published the first observation of 2D MoS2 cracking at the atomic level. This study is expected to contribute to the applications of new 2D materials.

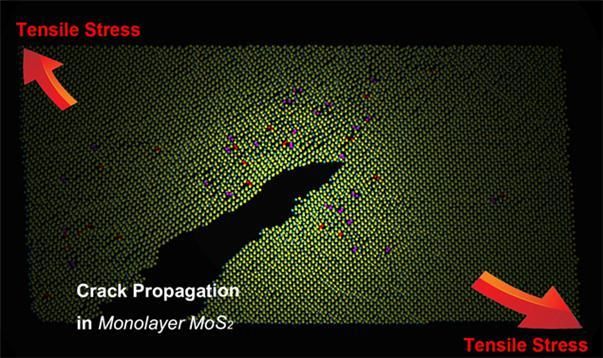

Schematic representation of the crack propagation in 2-D MoS2 at the atomic level. Dislocations shown with red and purple dots are visible at the crack tip zone. Internal tensile stresses are represented by red arrows.

IBS

Obviously when a certain force is applied to a material a crack is created. Less obvious is how to explain and predict the shape and seriousness of a crack from a physics point of view. Scientists want to investigate which fractures are likely to expand and which are not .Materials are divided into ductile and brittle: Ductile materials, like gold, withstand large strains before rupturing; brittle materials, like glass, can absorb relatively little energy before breaking suddenly, without elongation and deformation. At the nano-level atoms move freer in ductile materials than in brittle materials; so in the presence of a pulling force (tensile stress) they can go out of position from the ordered crystal structure, or in technical terms - they dislocate. So far, this explanation (Griffith model) has been applied to cracking phenomena in bulk, but it lacks experimental data at the atomic or nano-scale.

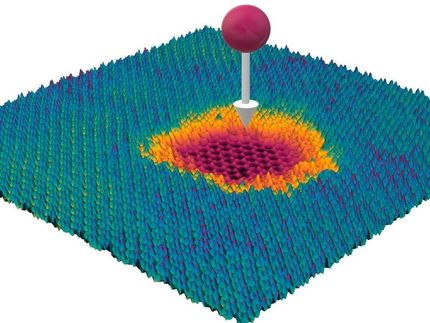

In this study, IBS scientists observed how cracks propagate on 2D MoS2 after a pore was formed either spontaneously or with an electron beam. "The most difficult point {of the experiments} was to use the electron beam to create the pore without generating other defects or breaking the sample," explains Thuc Hue Ly, first author of this study. "So we had to be fast and use a minimum amount of energy."

The atomic observations were done using real-time transmission electron microscopy. Surprisingly, even though MoS2 is a brittle material, the team saw atom dislocations 3-5 nanometers (nm) away from the front line of the crack, or crack tip. This observation cannot be explained with the Griffith model.

In order to create conditions that represent the natural environment, the sample was exposed to ultraviolet (UV) light. This caused the MoS2 to oxidize; atom dislocations occurred more rapidly and the stretched region expanded to 5-10 nm from the crack tip.

"The study shows that cracking in 2D materials is fundamentally different from cracking in 3D ductile and brittle materials. These results cannot be explained with the conventional material failure theory, and we suggest that a new theory is needed," explained Professor LEE Young Hee (CINAP).

Original publication

Other news from the department science

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.