Magnetic bits by electric fields

Making use of local electric fields for writing and deleting individual nanoscale magnetic skyrmions

Advertisement

Physicists of the University of Hamburg in Germany have demonstrated for the first time the controlled writing and deleting of individual nanoscale magnetic knots – so called skyrmions – by applying local electric fields to an ultrathin film of iron as data storage medium. These tiny knots in the magnetization of ultrathin metallic films exhibit an exceptional stability and are highly promising candidates for future ultra-high density magnetic recording. So far, they could be manipulated by local spin-currents and magnetic fields only. Now the research group at the University of Hamburg, headed by Roland Wiesendanger, report on the first electric-field controlled manipulation of nanoscale magnetic skyrmions. This work paves the way towards a new energy-efficient data storage technology in which electric fields can switch between two distinct magnetic states encoding the bits of information.

Magnetic skyrmions are highly complex three-dimensional spin textures, where the individual magnetic moments rotate in a unique sense by 360° from one side to the other. These objects have particle-like character and a non-trivial topology in contrast to the commonly known ferromagnetic state for which all magnetic moments are aligned in the same direction. Accordingly, skyrmions carry a topological charge „1“, whereas the ferromagnetic state has a topological charge of „0“.

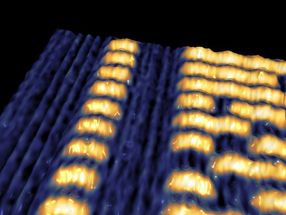

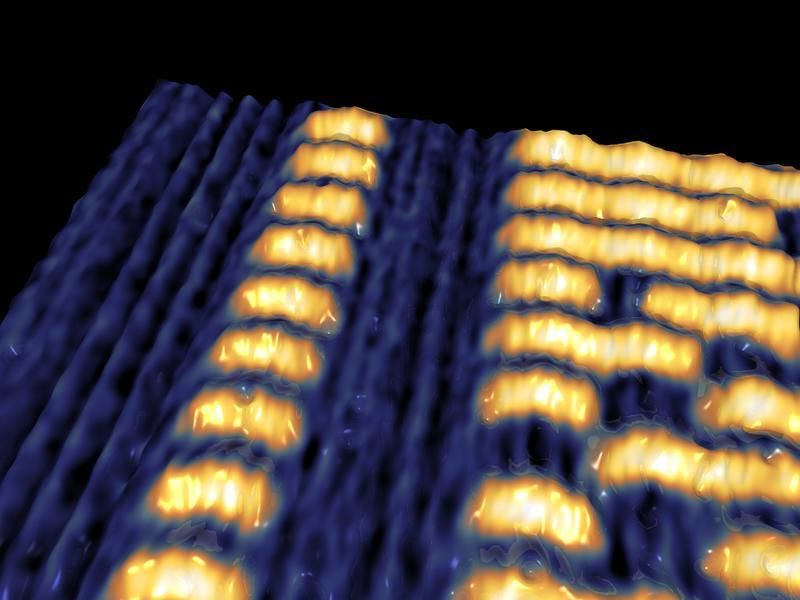

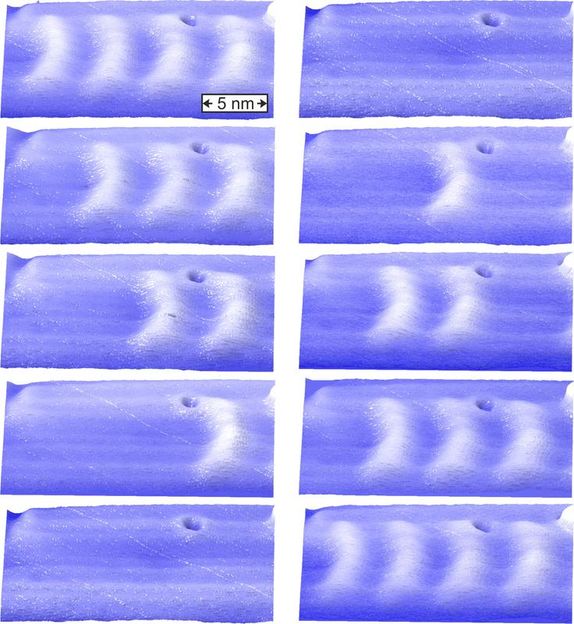

In conventional magnetic data storage devices, the magnetic bits still consist of a rather large number of magnetic atoms with parallel aligned magnetic moments in two opposite directions, thereby encoding the „1“ and „0“ as bits of information. These two different magnetic states of conventional magnetic data storage systems can only be transformed into one another by magnetic fields or by spin currents, but not by electric fields because they are symmetry-related. This is different in the case of skyrmions: they are topologically distinguishable from the ferromagnetic state and these two states can therefore be transformed into one another by local electric fields. The research group of Roland Wiesendanger could indeed show that tiny magnetic skyrmions can be switched by the local electric field present between the sharp tip of a scanning tunneling microscope and a sample consisting of a three atomic-layer thick iron film on an iridium substrate, and that the direction of the local electric field determines whether skyrmions can be created or deleted (see figure 1). Amazingly, the individual skyrmions in that three atomic layer thick iron film have a size of only 2.2 nm x 3.5 nm and can be aligned along linear tracks as shown in figure 2. Conventional magnetic bits would never be stable in that size regime, whereas magnetic skyrmions pave the way towards ultra-dense data storage devices. Moreover, the demonstration of controlled electric-field induced writing and deleting of individual magnetic skyrmions can lead to an unprecedented energy-efficient way to store information since spin currents are no longer needed to switch between the two different bit states.

Nanoscale skyrmions ligned up along linear tracks in ultrathin iron films being three atomic layers thick only. The magnetization direction rotates within atomic-scale distances within the skyrmions (bright contrast features), while it is constantly pointing perpendicular to the film plane in the ferromagnetic regions (dark blue regions). The image was recorded with a spin-polarized scanning tunneling microscope, which is the only technique that can reveal magnetization distributions with atomic-scale accuracy.

A. Kubetzka, P.-J. Hsu und R. Wiesendanger, Universität Hamburg

Controlled deleting (left) and writing (right) of individual nanoscale magnetic skyrmions by local electric fields. Between the individual images the tip of a scanning tunneling microscope was properly positioned and the local electric field was raised for a short time up to +3 V/nm (left) or -3V/nm (right). A single atomic vacancy in the ultrathin iron film (dark contrast) indicates the extremely small scale of the written and deleted skyrmions (bright contrast).

A. Kubetzka, P.-J. Hsu und R. Wiesendanger, Universität Hamburg