Here comes the long-sought-after iron-munching microbe

A microbe that ‘eats’ both methane and iron: microbiologists have long suspected its existence, but were not able to find it - until now. Researchers at Radboud University and the Max Planck Institute for Marine microbiology in Bremen discovered a microorganism that couples the reduction of iron to methane oxidation, and could thus be relevant in controlling greenhouse gas emissions worldwide.

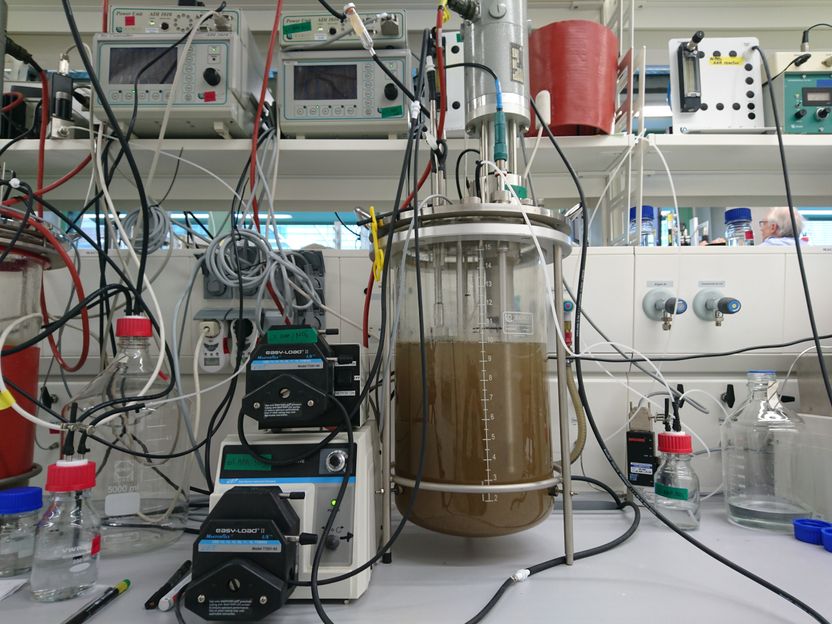

One of the bioreactors, in which Kartal and his colleagues found the rust-munching microbes.

MPI für Marine Mikrobiologie

The Twentekanaal near Enschede.

MPI für Marine Mikrobiologie

The balance between methane-producing and -consuming processes has a major effect on the worldwide emission of this strong greenhouse gas into our atmosphere. The team of microbiologists and biogeochemists now discovered an archaeon - the other branch of ancient prokaryotes besides bacteria – of the order Methanosarcinales that uses iron to convert methane into carbon dioxide. During that process, reduced iron become available to other bacteria. Consequently, the microorganism initiates an energy cascade influencing the iron and methane cycle and thus methane emissions, describe first authors Katharina Ettwig (Radboud University) and Baoli Zhu (Hemholtz Zentrum München) in the paper.

Application in wastewater treatment

Besides, these archaea have another trick up their sleeve. They can turn nitrate into ammonium: the favourite food of the famous anammox bacteria that turn ammonium into nitrogen gas without using oxygen. “This is relevant for wastewater treatment”, says Boran Kartal, a microbiologist who recently moved from Radboud University to the Max Planck Institute in Bremen. “A bioreactor containing anaerobic methane and ammonium oxidizing microorganisms can be used to simultaneously convert ammonium, methane and oxidized nitrogen in wastewater into harmless nitrogen gas and carbon dioxide, which has much lower global warming potential.” The same process could also be important in paddy fields, for example, which account for around one fifth of human-related emissions of methane.

Closer than expected

While there have been numerous indications that such iron-dependent methane oxidizers existed, researchers have never been able to isolate them. Surprisingly, they were right in front of our doorstep: “After years of searching, we found them in our own sample collection”, says microbiologist Mike Jetten of Radboud University with a smile. “We eventually discovered them in enrichment cultures from the Twentekanaal in The Netherlands that we’ve had in our lab for years.”

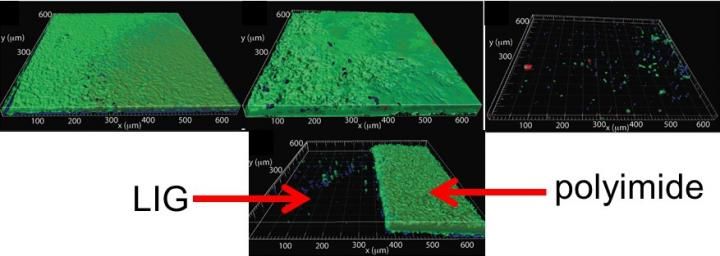

“Based on the genetic blueprint of these microorganisms”, Kartal adds, “we hypothesized that they could convert particulate iron - basically rust - coupled to methane oxidation. So we tested our hypothesis in the lab – and these organisms did the trick.” In the next step, Kartal wants to look closer into the details of the process. “These findings fill one of the remaining gaps in our understanding of anaerobic methane oxidation. Now we want to further investigate which protein complexes are involved in the process.”

Billions of years ago

The newly discovered process could also lead to new insights into the early history of our planet. Already 4 to 2.5 billion years ago, Methanosarcinales archaea might have abundantly thrived under the methane-rich atmosphere in the ferruginous (iron holding) Archaean oceans,. More information on the metabolism of this organism can therefore shed new light on the long-standing discussion of the role of iron metabolism on early earth.

Original publication

Most read news

Original publication

Katharina F. Ettwig, Baoli Zhu Daan R. Speth, Jan T. Keltjens, Mike S. M. Jetten, Boran Kartal; "Archaea catalyze iron-dependent anaerobic oxidation of methane"; PNAS; 2016

Topics

Organizations

Other news from the department science

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.